Recently, I was invited to join a panel of wonderful BookTubers on a livestream hosted by the channel @MattonBooks to discuss some of the highs and lows of our reading in 2024. It was the first time I’ve done that kind of annual wrap-up, and I’ve briefly summarized here on Substack my responses to the 11 questions asked of the panel (the full discussion in the video lasts four hours!).

1. What was my favorite reread of the year?

Since starting my channel three years ago, I’ve reread many books from decades ago in order to refresh my memory and update my opinions about them. That was particularly true as I prepared for my videos last year about King Arthur, Connie Willis and Jack Vance. Some of my favorite rereads from 2024 included Jack Vance’s Lyonesse trilogy, Mary Stewart’s Merlin trilogy, and Maurice Druon’s Accursed Kings historical fiction series.

But the one I enjoyed the most was my reread of Connie Willis’ Blackout/All Clear duology. I reread her Oxford Time Travel series within a span of three months and it gave me a greater appreciation for the attention to detail (both historical and plot-wise) in the concluding duology and its subtle linkages to the earlier books in the series.

2. What was my favorite series I started this year but didn’t finish?

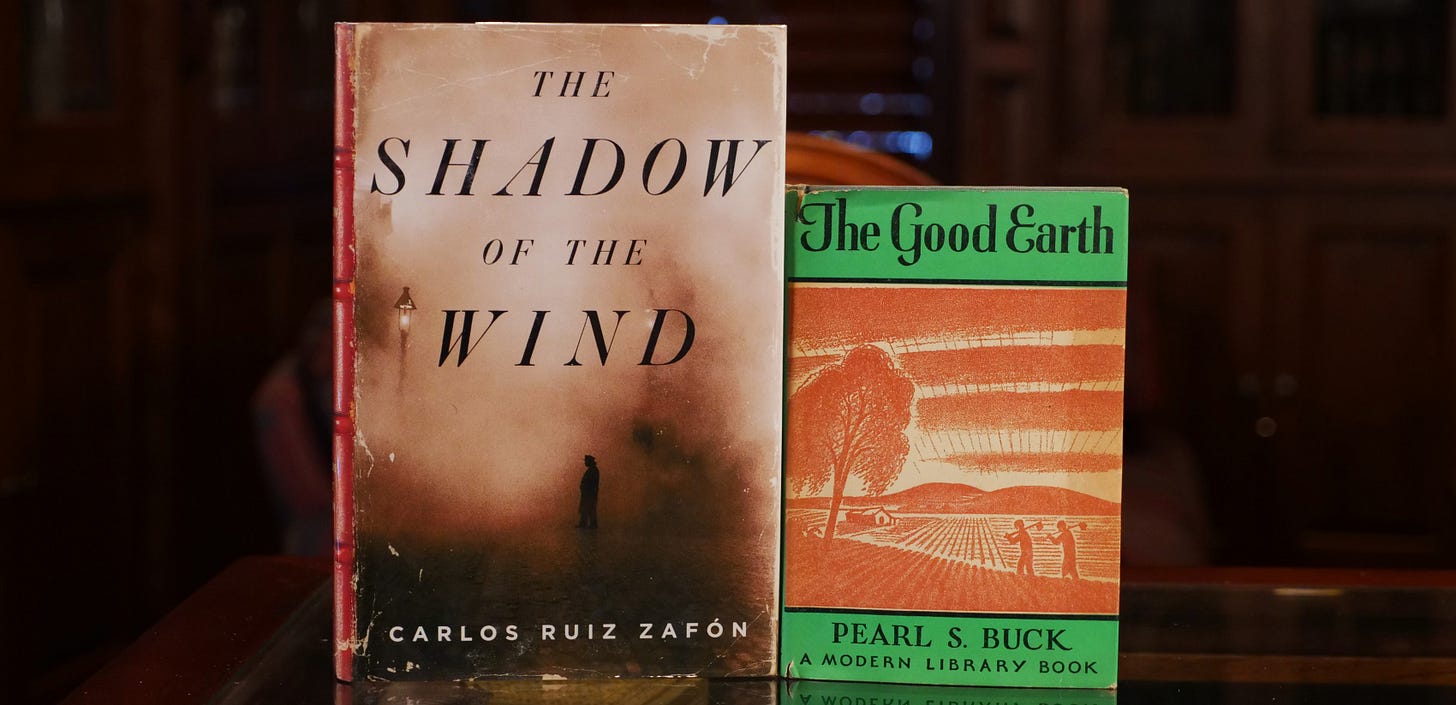

Two runners-up are Ken Liu’s Dandelion Dynasty series and Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s Cemetery of Forgotten Books series. I’ve completed the first two books in both series. The winner, though, is Winston Graham’s Poldark Saga, a 12-book, multigenerational historical fiction series set in Cornwall in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that he wrote over a six-decade period from 1945 to 2002.

3. What was my favorite series I finished reading this year?

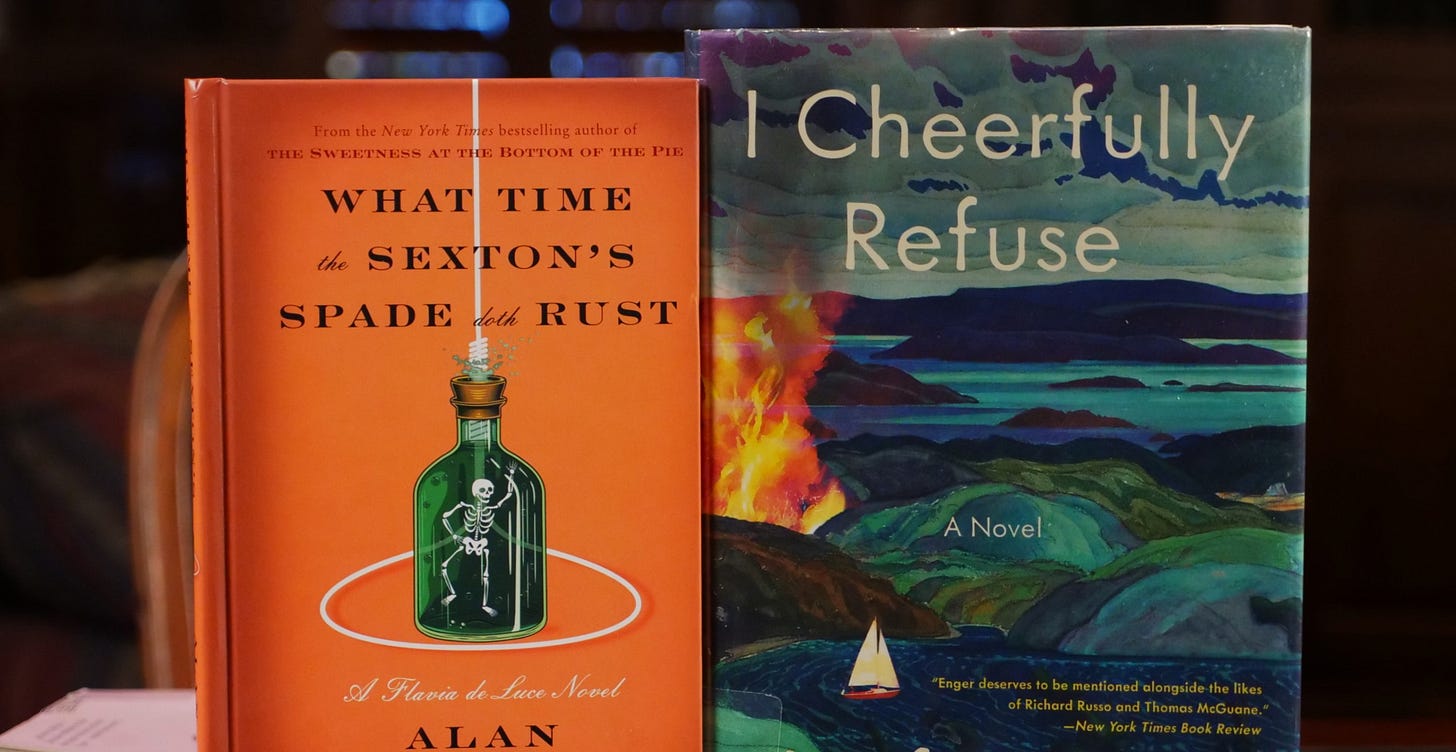

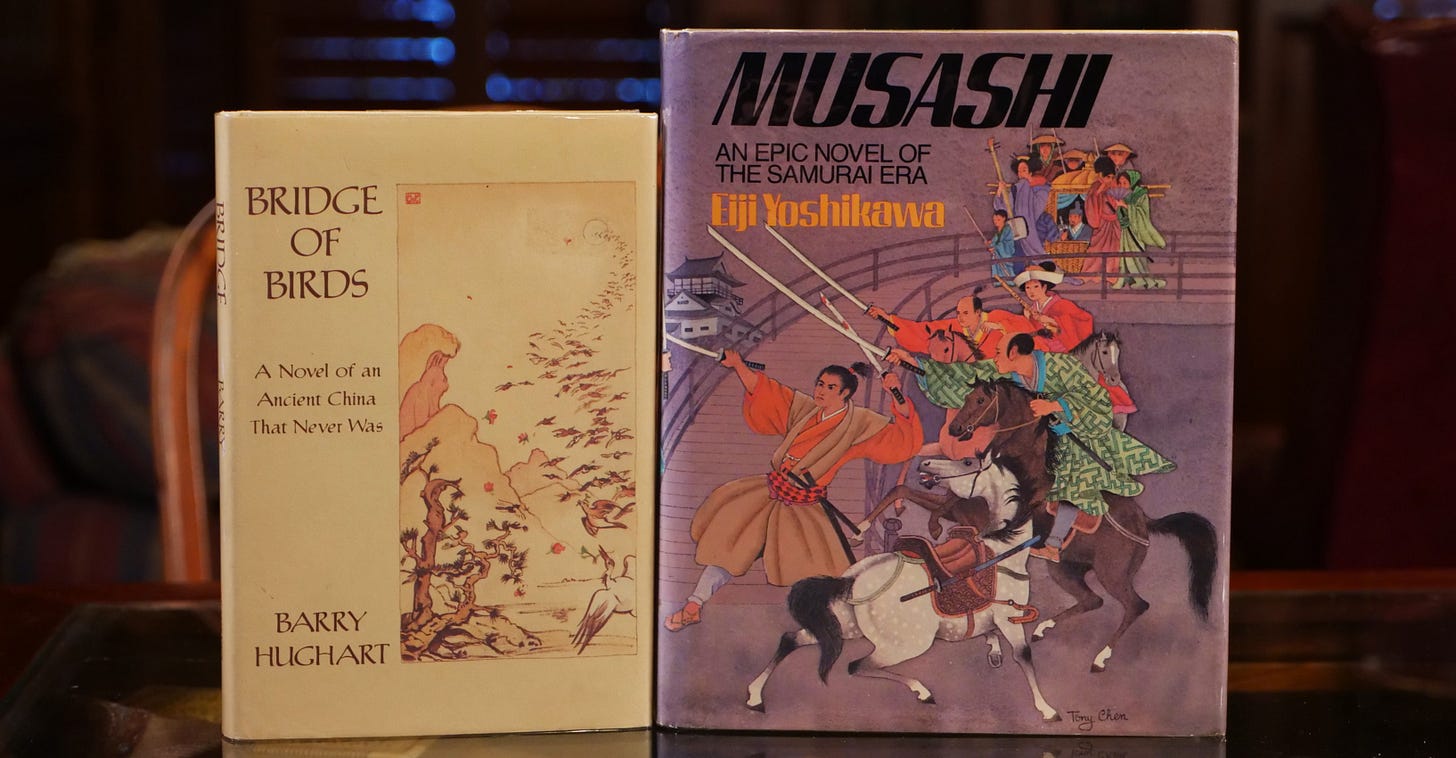

This was a tough question to answer. Not counting my rereads, I didn’t finish very many series, but the ones I did were excellent. My two runners-up were Arkady Martine’s terrific Teixcalaan, a science fiction duology comprising A Memory Called Empire and A Desolation Called Peace) and Alan Bradley’s wonderful, 11-volume Flavia de Luce mystery series that’s written for adults but features a precocious 11-year-old sleuth. Topping them, though, was Barry Hughart’s delightful The Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox fantasy trilogy from the 1980s and early 1990s (Bridge of Birds, The Story of the Stone, and Eight Skilled Gentlemen) inspired by traditional Chinese myths and folktales.

4. What was my favorite author I read for the first time this year?

I’d been aware of Barry Hughart for decades, but I’d never gotten around to reading his The Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox trilogy until last year. I’m kicking myself for waiting so long. Alas, those are the only novels he ever published.

5. What was my favorite new character of the year?

This was a tossup between Master Li Kao from Barry Hughart’s series and Davy from the 1964 novel Davy by Edgar Pangborn (which reads like a bawdy hybrid of John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (also titled Re-Birth in the US), Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker and Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones).

6. What was my biggest surprise of the year?

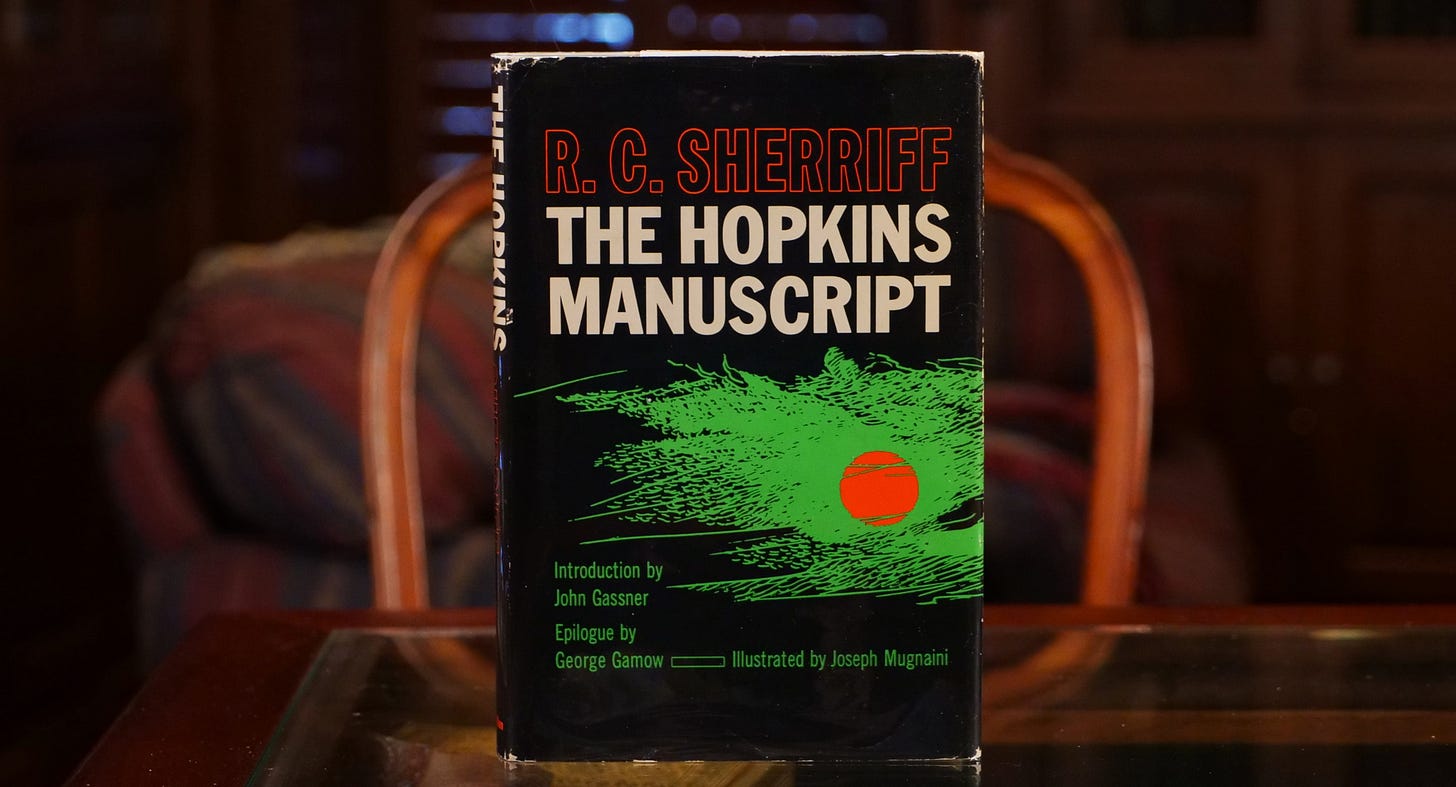

I’ve been reading a lot of apocalyptic/post-apocalyptic fiction as part of a comprehensive overview I’m preparing about the history of that subgenre. R.C. Sherriff’s 1939 novel The Hopkins Manuscript is an obscure one I’d never heard of until just a couple of years ago when a new edition brought it back into print. It’s a somewhat old-fashioned mashup of H.G. Wells catastrophe fiction and Wodehousian social comedy designed as an allegorical warning to the British public of the looming threat of World War II. For a story about a fussy, self-absorbed retired schoolmaster who frets about his prize-winning chickens more than he does about the end of the world, it was far more enjoyable than I expected it to be.

7. What was my biggest disappointment of the year?

I had three significantly disappointing reads last year. Two I strongly disliked, while the third was a fun read that failed to meet the high expectations I had for it.

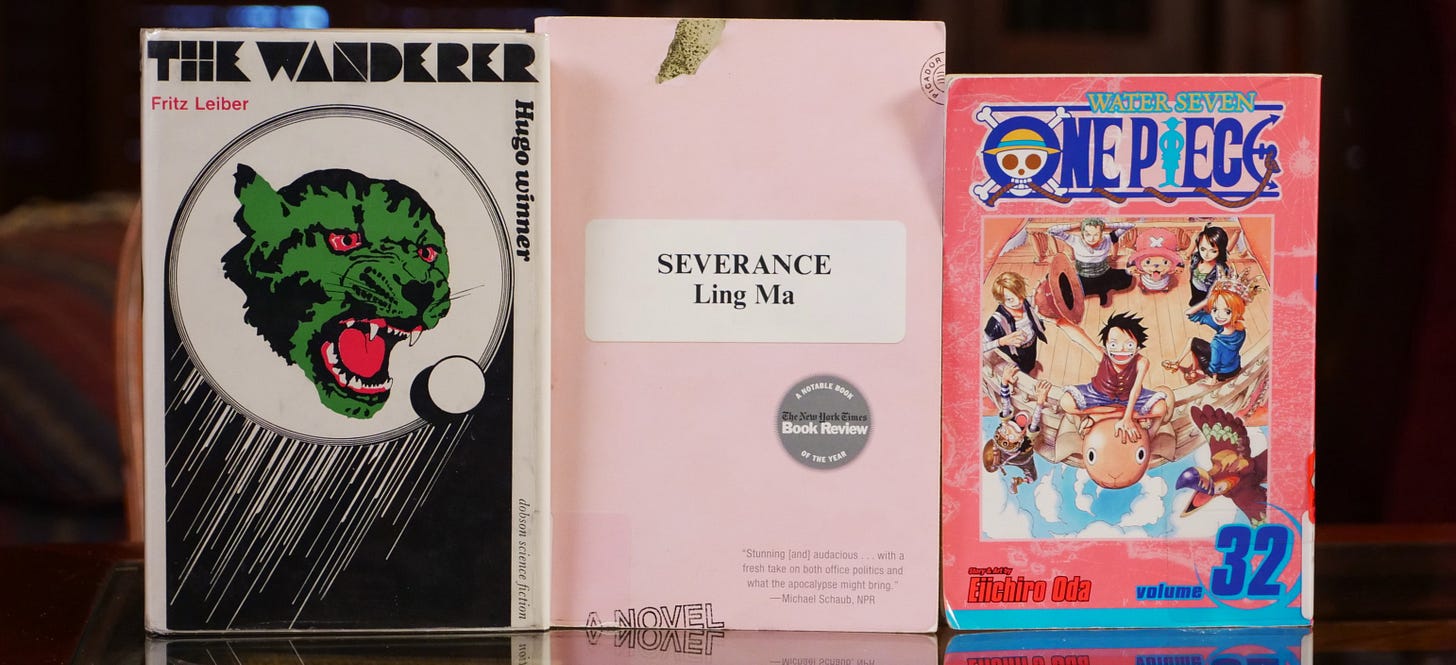

Fritz Leiber’s 1964 novel The Wanderer felt like a bad knock-off of an Irwin Allen disaster movie with the bizarre twist in which a sexy feline space alien destroys the moon to mate with a human astronaut. Leiber has written some great works of fiction in my opinion, but this isn’t one of them, despite it winning the Hugo Award for best novel. Here, Leiber’s seemingly desperate desire to be edgy and transgressive got in the way of telling a good story.

Ling Ma’s 2018 zombie apocalypse novel Severance suffered from a shallow, bored, self-absorbed and perpetually snarky main character whose lack of interest in anything in her life made her utterly uninteresting. Making matters worse, the author spent more time in the book dwelling on the main character’s pathological ennui (told mostly through disjointed flashbacks) than on her efforts to survive a brain-eating virus pandemic. The author seemed to be using the zombie plotline as an allegorical prop to comment on the soul-sucking nature of work as a corporate office drone, but the dots were poorly connected and it fell completely flat for me.

And then there were the 32 One Piece volumes I read, comprising the first three arcs of that manga series. I enjoyed reading it, and I delighted in its inventive worldbuilding and in the positive values it promotes. However, it hasn’t come close to living up to the expectations I’d formed after hearing several BookTubers sing its praises.

The 3,600+ pages I read of One Piece contained significant breadth of ideas, but very little depth. Many serious themes were namedropped or hinted at but were never really explored by the author, while the plot itself was highly repetitive, relying on overly long and nonsensical fight scenes to solve almost every problem the main characters encountered. It clearly was written for juvenile readers, with its short, dialogue-heavy sentences, fourth grade vocabulary, and cartoonish characters who possess the impulse control and emotional stability of immature adolescents. Much like John Williams’ acclaimed novel Stoner, it seems like a blank slate onto which readers can project their own imagined emotional and thematic depth and complexity.

8. What was my favorite new release of the year?

I read only two fiction titles published in 2024 – Alan Bradley’s What Time the Sexton’s Spade Doth Rust (the 11th volume in his Flavia de Luce mystery series) and Leif Enger’s I Cheerfully Refuse (a post-apocalyptic novel about a husband’s grief and his somewhat surreal efforts to reconnect with his dead wife that draws inspiration from the tale of Orpheus in Greek mythology). I enjoyed both books quite a bit.

9. What book that I read this year would I recommend to anyone?

I’d recommend two books. Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s The Shadow of the Wind combines elements of several different genres, including historical fiction, literary fiction and mystery, as well as light touches of fantasy (magical realism) and horror, giving it potential crossover appeal to different types of readers.

I’d also suggest Pearl S. Buck’s novel The Good Earth, which follows the ups and downs of a peasant family in rural China at the start of the 20th century during a period of substantial upheaval in the country. It’s a poignant story of ambition, self-improvement and the importance of staying grounded and true to one’s core values. It was the top-selling novel in the US for two straight years in 1931 and 1932, and it won Buck the Nobel Prize for Literature a few years later.

10. What was my favorite book of the year?

In terms of pure fun and enjoyment while reading, Barry Hughart’s 1984 novel Bridge of Birds (the first book in his Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox fantasy trilogy) wins the prize.

However, the book that’s stuck with me the most since reading it is Eiji Yoshikawa’s 1935 classic of Japanese literature Musashi. It’s a monumental historical fiction epic set at the start of the 17th century that follows real-life, legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi as he progresses from a teenage bully and reprobate into one of Japan’s foremost thought leaders on the meaning and practice of honor, self-discipline and personal enlightenment. Musashi the man holds a place in Japanese philosophy similar to that of Marcus Aurelius in Western philosophy.

I’ll also add that reading Musashi and One Piece around the same time made me realize how much One Piece seems to be patterned after Yoshikawa’s epic. Both feature impulsive youths wandering the world on obsessive quests to become the world’s greatest samurai (or pirate). The main characters have bounties placed on their heads. They gather ‘found families’ of loyal followers. They fight momentous duels with adversaries that propel them forward in their quests. And they explore the meaning of life, love and honor along the way. However, Musashi has considerably more depth than One Piece.

11. What book am I most looking forward to reading in 2025?

Although I’m very eager to read The Navigator’s Children (Tad Williams’ latest volume in his Last King of Osten Ard series) and Written on the Dark (Guy Gavriel Kay’s upcoming novel), I’m already familiar enough with those authors’ works that I’m not counting them here among my most-anticipated reads.

Instead, I’ll highlight a few classics and one modern work, most of which are part of a wide-ranging historical fiction project I’m targeting for later this year on my channel and here on Substack. The modern work is Dennis Lehane’s 2008 novel The Given Day, which was highly recommended to me by Josh at the YouTube channel @RedFuryBooks. The classics include Pearl S. Buck’s 1933 translation of the traditional Chinese novel The Water Margin (Buck’s abridged version is titled All Men Are Brothers), Alfred Duggan’s 1953 novel The Little Emperors, Thomas Costain’s 1956 novel The Tontine, and several of Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances and detective stories from the 1920s-1960s.

And as part of my ongoing exploration of the roots of modern fantasy, I also plan to read Austin Tappan Wright’s mostly forgotten utopian novel Islandia, which was first published in 1942 and is famous for its worldbuilding that’s said to rival Tolkien’s for its breadth and depth.