ISFDB is an invaluable resource for readers and book collectors

A history of speculative fiction bibliographies

Today, readers and collectors of speculative fiction have a wide variety of helpful online tools at their disposal. There are apps and websites such as LibraryThing, StoryGraph, Collectorz, Libib and Goodreads that can catalog book collections, track one’s reading history, and share reviews and recommendations with other users. Bookselling sites such as Abebooks, Amazon and eBay provide a bird’s-eye view of the general availability and pricing of scarce book editions, while smaller sites such as Pangobooks and Whatnot are useful places to rummage for bargains.

But what if you want to know every work of speculative fiction an author ever wrote, as well as when and where they were published?

What about their essays, book reviews and other works of nonfiction?

Where can you find a list of every hardcover edition of a particular SF title, including information to help you identify a first edition?

Perhaps you need the pseudonyms under which an author wrote.

Maybe there’s a fanzine or obscure specialty press whose bibliography you want to know.

How can you identify every book cover an illustrator has created?

And how can you determine how limited a limited edition is?

Answers to these and other questions about authors, titles, publishers, illustrators and editors in the science fiction, fantasy and horror genres can be found by searching the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (isfdb.org).

ISFDB is a gold mine of information for collectors, genre researchers and curious readers. First launched in the mid-1990s, the site has grown exponentially since then through the dedicated efforts of its users to add, update and confirm database entries, similar to Wikipedia’s approach to content creation.

I prioritize hardcover first editions in my collection, and ISFDB helps me identify if and when a title has ever been published in that format.

I also love short fiction, and ISFDB catalogues the magazine issues, anthologies and collections in which a story has appeared, making it much easier to find a copy to read.

In fact, I regularly use ISFDB for all of the questions I listed at the start of this essay.

However, back when I started collecting SF books more than 40 years ago, it was much harder to find that information. Online sites such as ISFDB didn’t exist. Instead, there was an assortment of lists, guides and bibliographies produced sporadically and in limited quantities over the years by fans and occasionally by booksellers. Sometimes they were published professionally with hardcover bindings, but often they took the form of typewritten pages photocopied and held together with staples or plastic comb bindings.

Early SF Bibliographies

Efforts to catalogue works of speculative fiction date back more than a century. In 1909, a librarian, Jean Hawkins, produced a bibliography of ghost and supernatural stories to help library patrons searching for such stories. It listed about 400 titles.

In 1933, SF fan Julius Schwartz prepared a list of about 600 science fiction, fantasy and weird fiction titles, but it contained only the author and title of each work and not any publication data.

In 1935, a group of SF fans led by William Crawford and D.R. Welch published a tiny chapbook titled Science Fiction Bibliography.

In 1944, A. Langley Searles, a doctoral candidate in chemistry at New York University and the editor of the SF fanzine Fantasy Commentator, began compiling the most ambitious bibliography of speculative fiction yet attempted. Parts of it were published in his fanzine, but it lacked some bibliographic details, and he never came close to completing it.

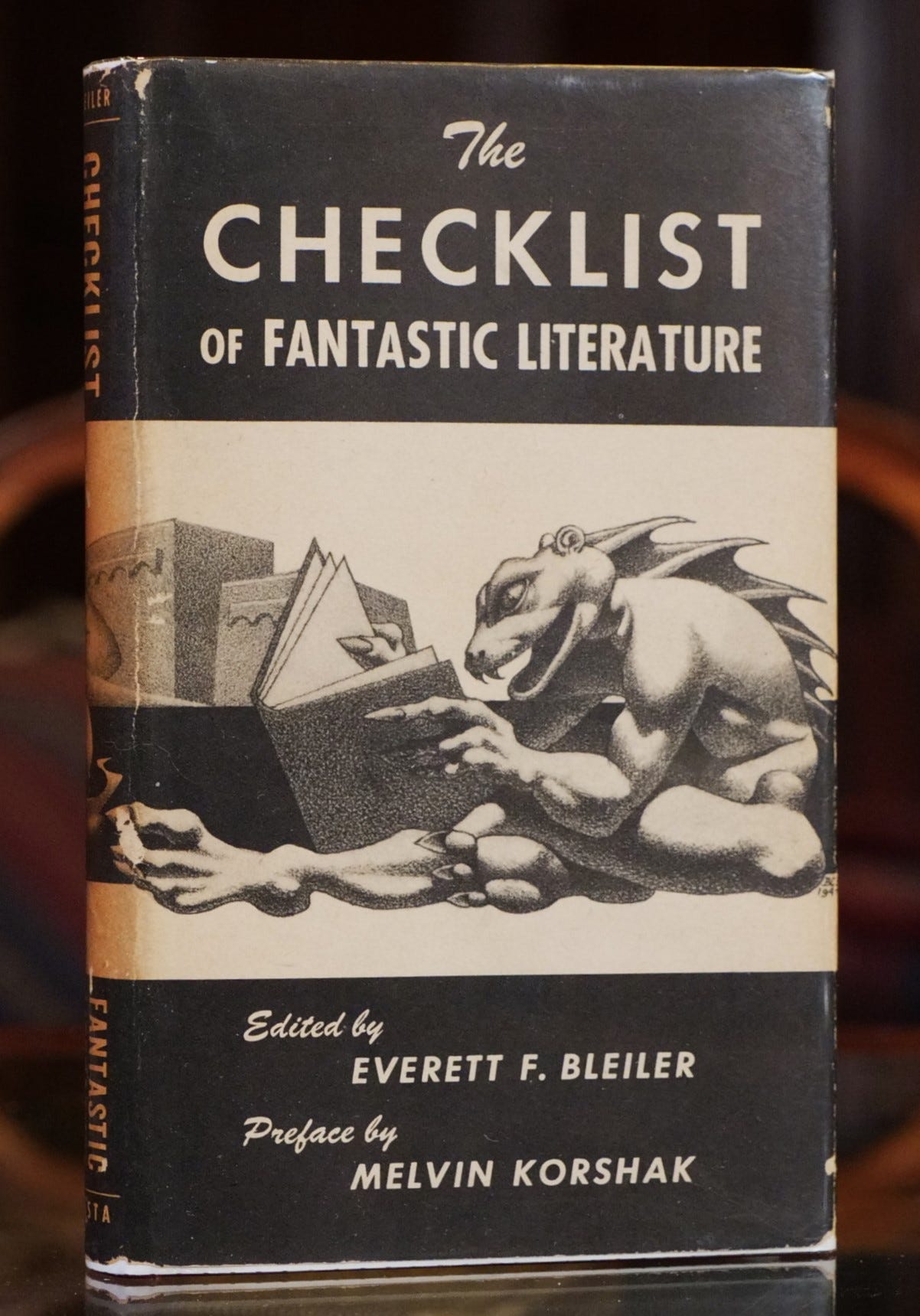

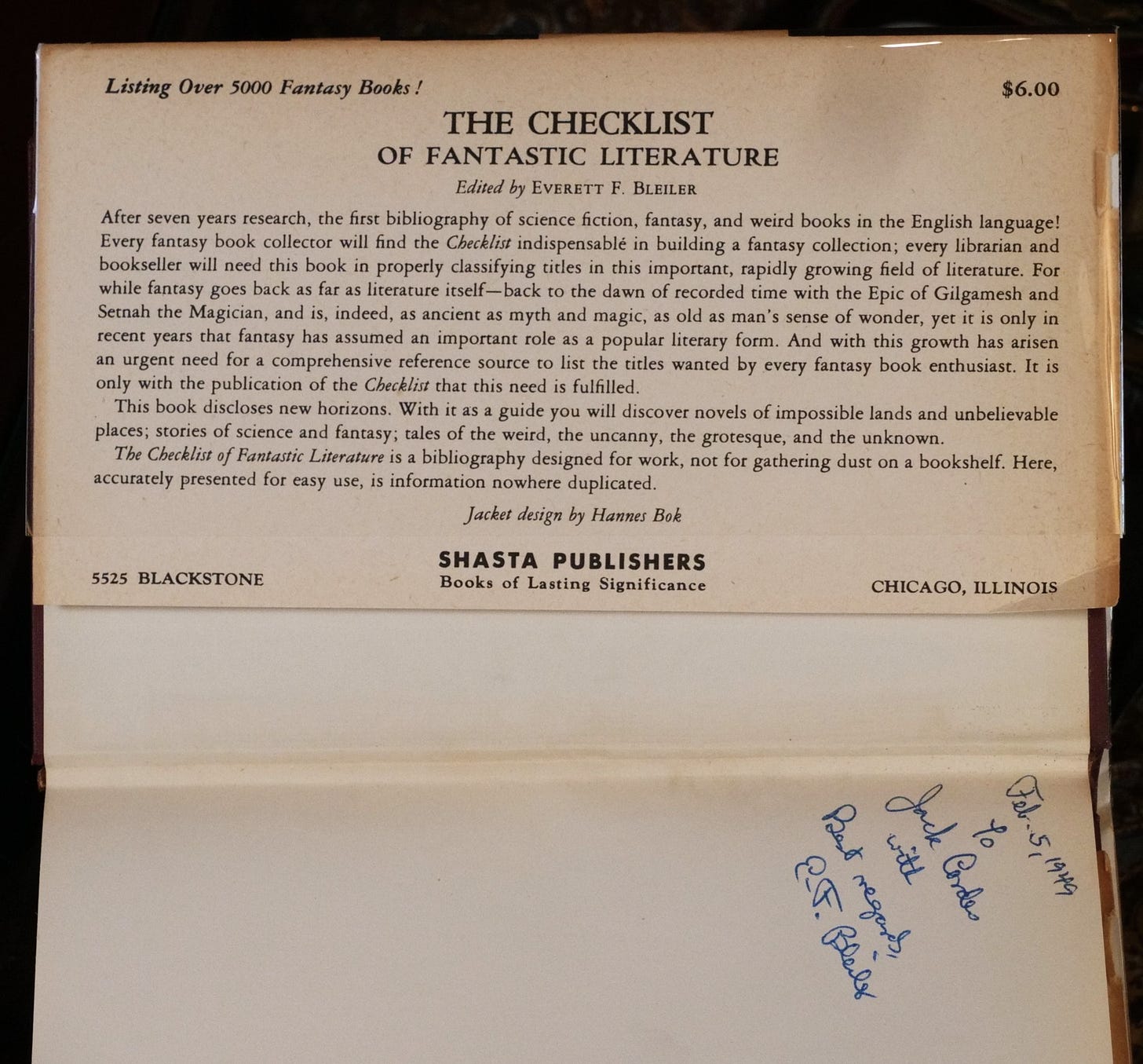

It wasn’t until 1948 and Shasta Publishers’ groundbreaking The Checklist of Fantastic Literature, edited by Everett F. Bleiler, that a serious attempt at a comprehensive bibliography of the science fiction, fantasy and horror genres was produced for the general public in a hardcover print run of a little over 1,900 copies.

[My essay containing a brief history of the Checklist and the pioneering small publisher Shasta can be found here.]

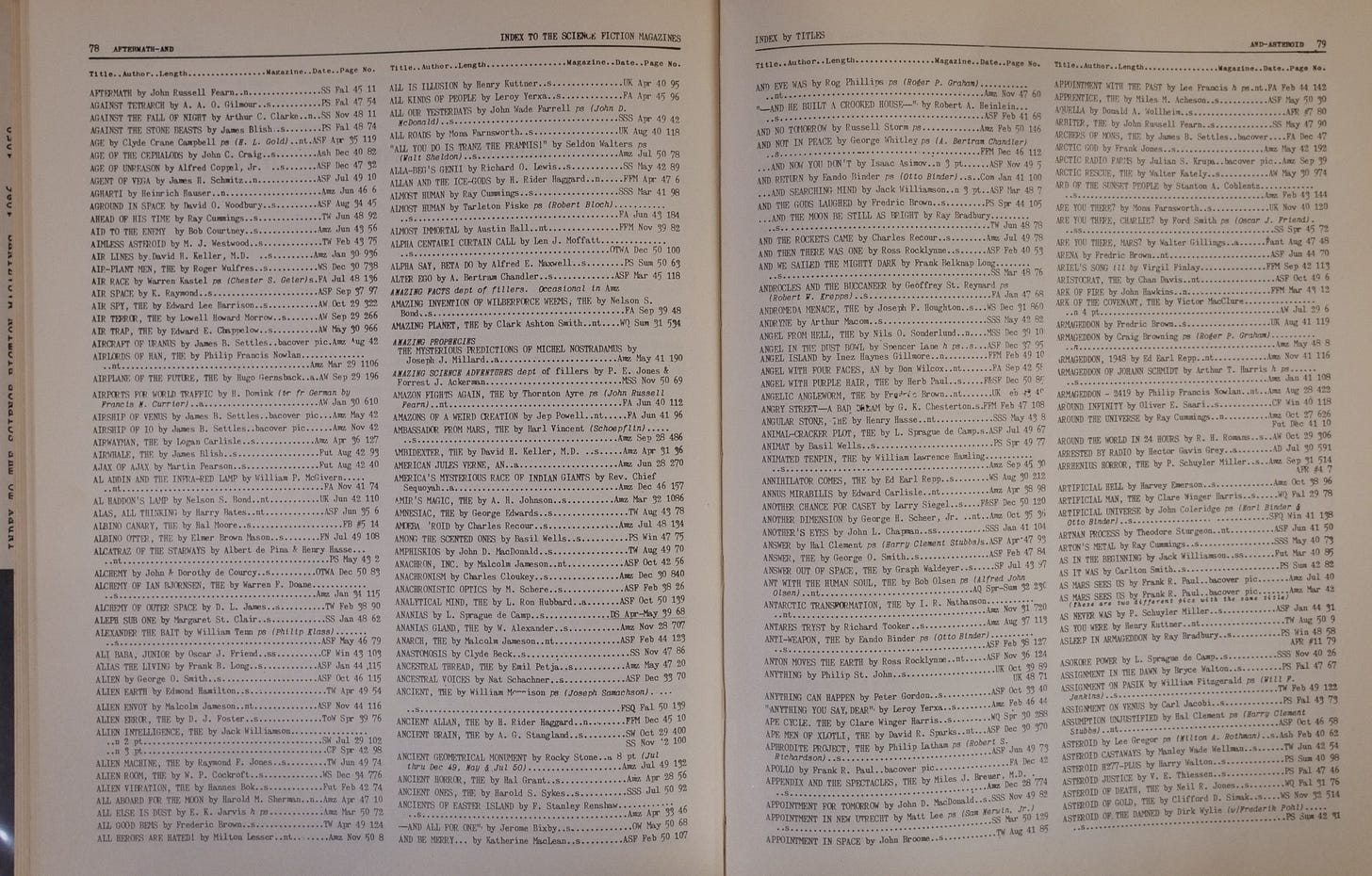

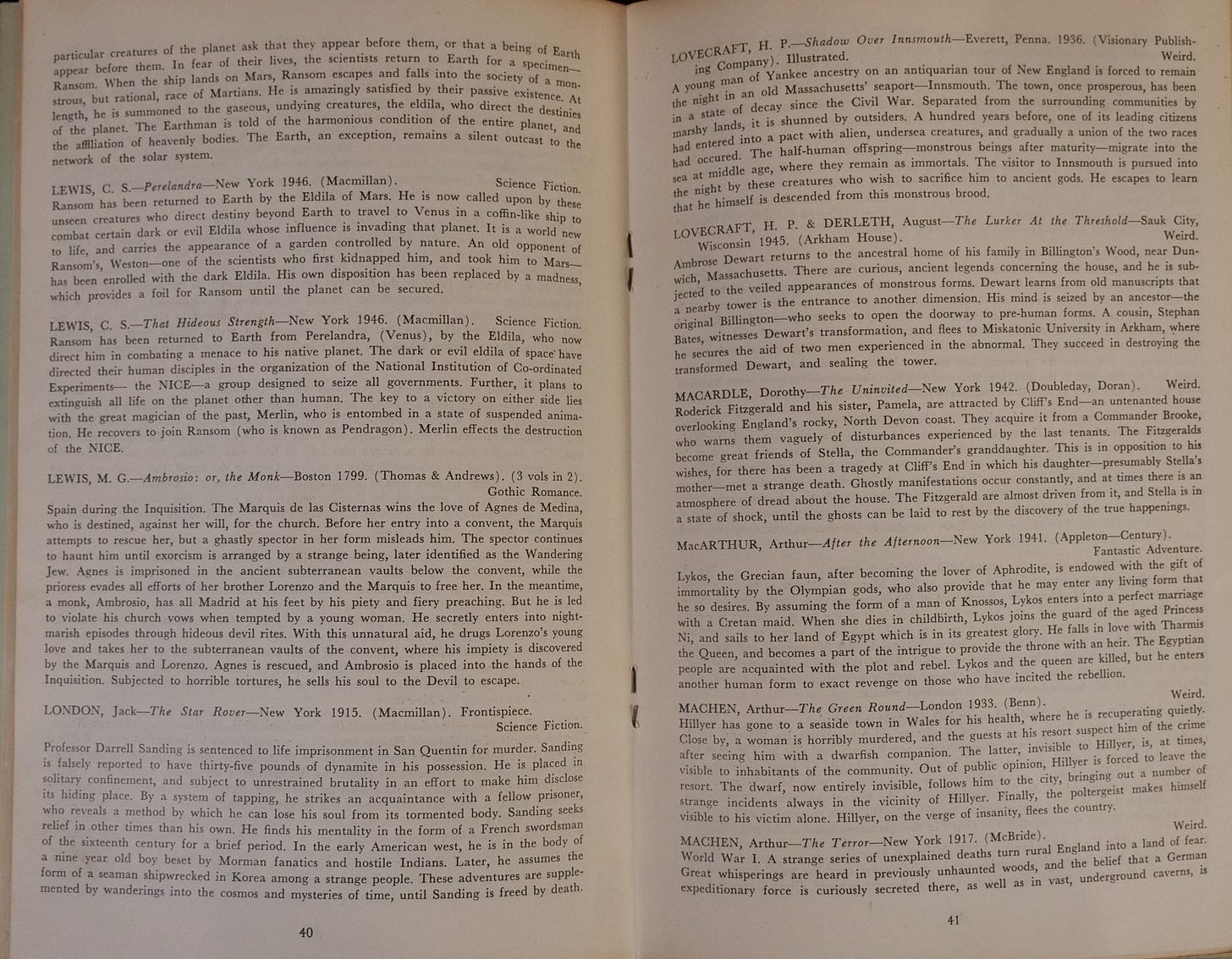

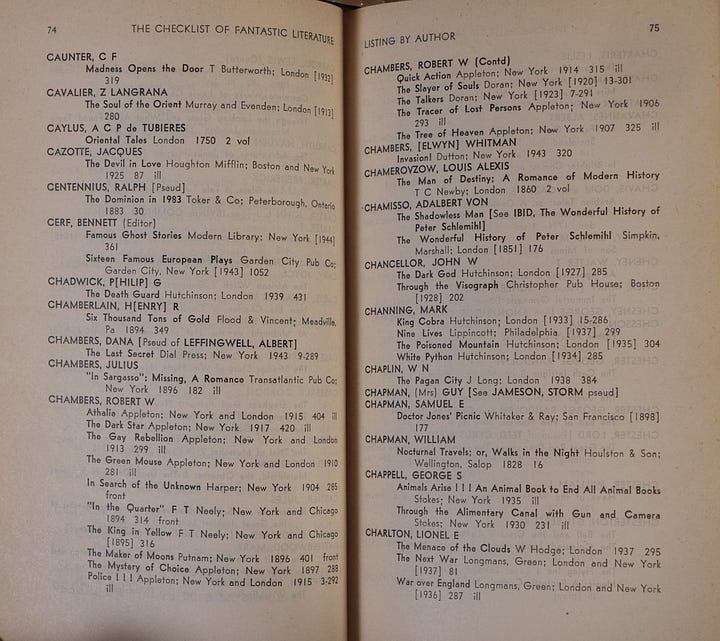

The Checklist consists of two lists: one sorted by author, detailing the titles of their works and their publication history; and the other simply an alphabetic list of titles identifying their authors. Around 3,000 authors and 5,000 titles are catalogued in it. It also has a short appendix listing several dozen critical, historical and biographical reference sources from that era related to speculative fiction.

For many years, Shasta’s Checklist was the definitive, if incomplete, guide for librarians, academics and collectors, and its success prompted efforts by others (typically fans and other amateurs) to produce similar bibliographies organized in different ways or tailored to specific purposes.

A few examples include:

The 1952 self-published hardcover Index to the Science-Fiction Magazines, 1926-1950, compiled and edited by Donald B. Day, that indexed every story printed in 58 of the most popular SF pulp magazines during that period;

the 1953 chapbook 333: A Bibliography of the Science-Fantasy Novel, edited by Joseph H. Crawford, James J. Donohue and Donald M. Grant (who later founded the speculative fiction publishing company that bears his name), that provided brief plot descriptions and bibliographic information for 333 SF novels;

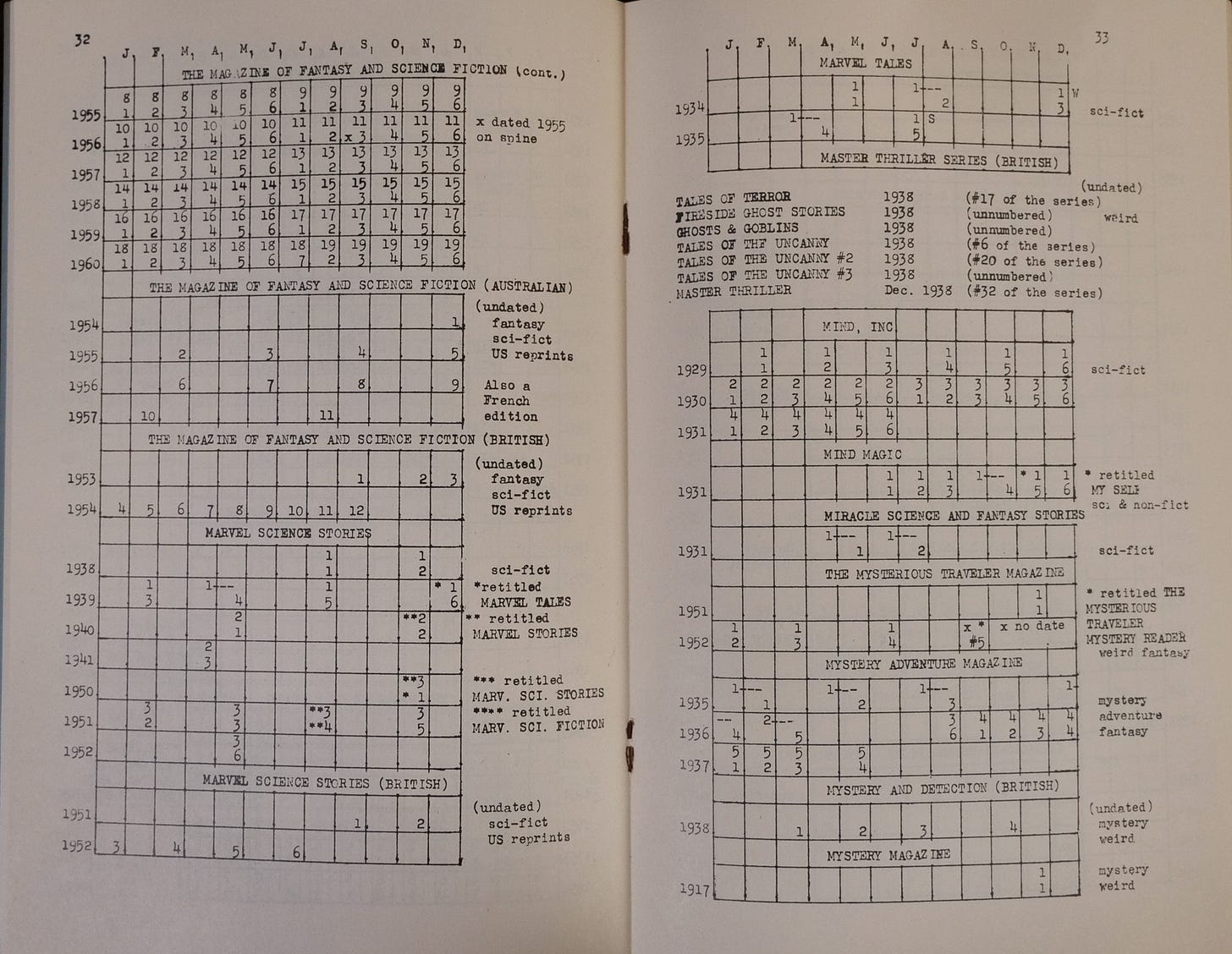

a 1961 self-published booklet titled The Complete Checklist of Science-Fiction Magazines, edited by Bradford M. Day, containing tables documenting the publication histories of around 300 SF pulp magazines;

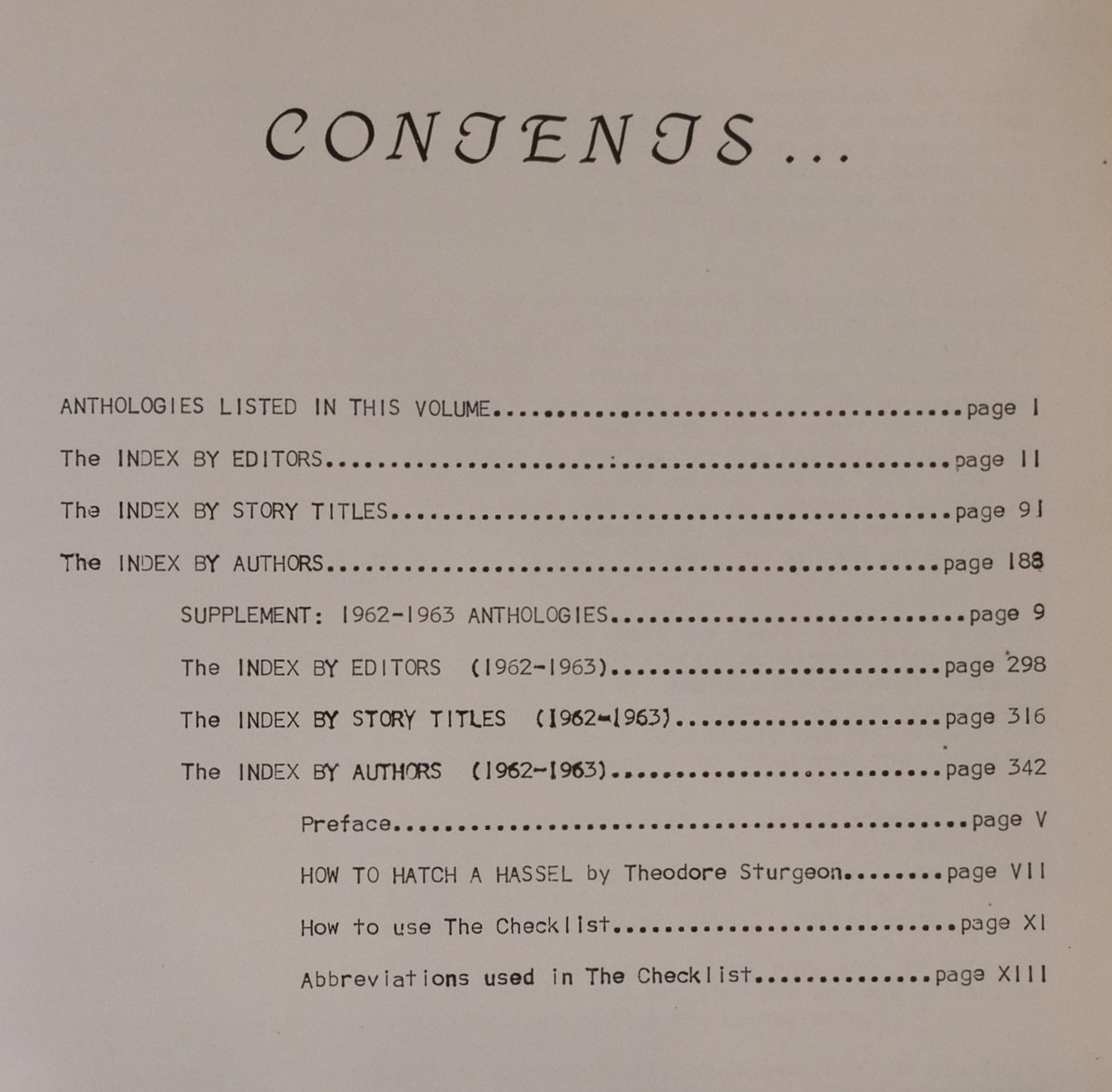

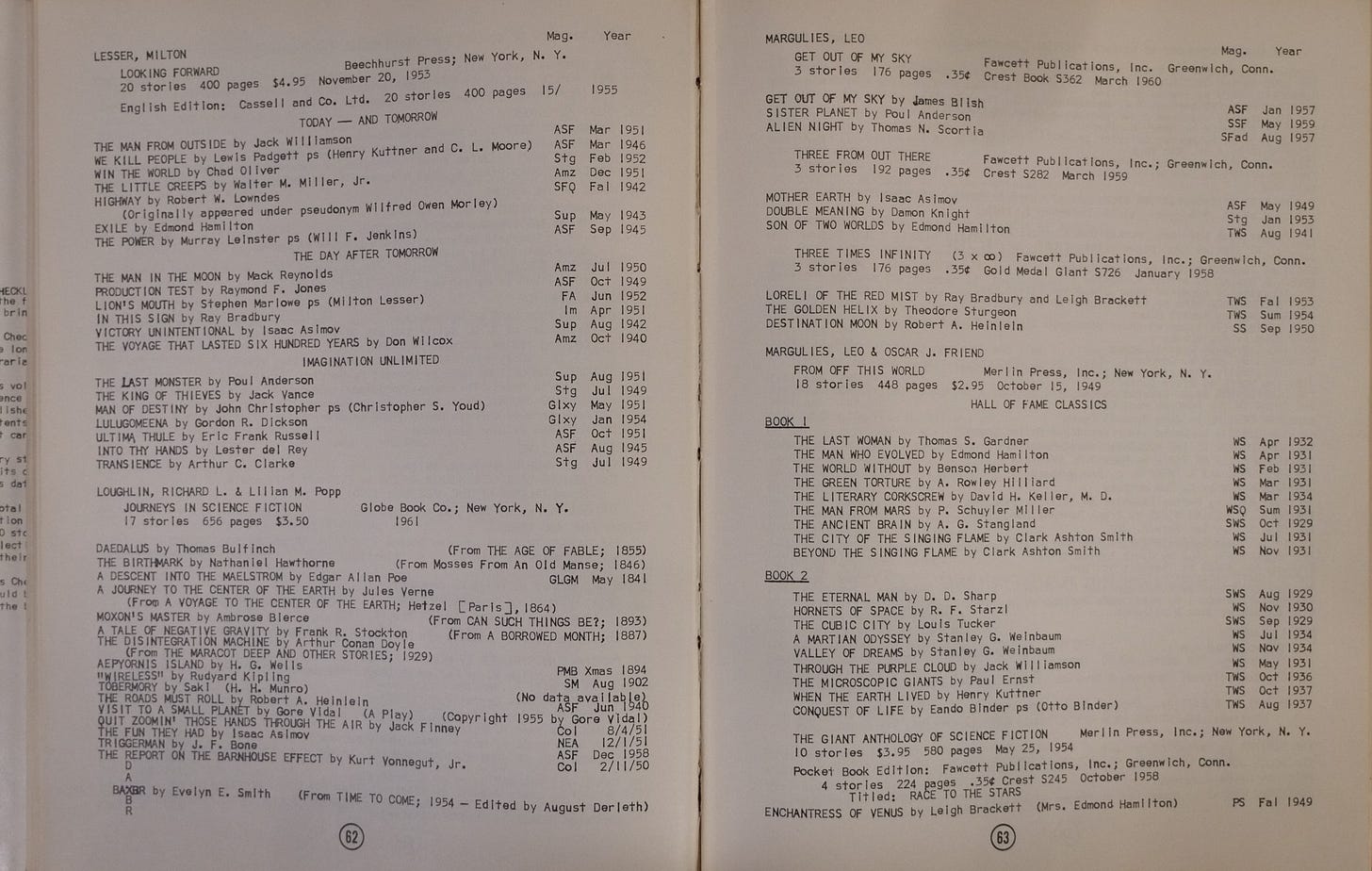

the 1964 self-published hardcover A Checklist of Science Fiction Anthologies, compiled and edited by W.R. Cole, that indexed the contents of nearly 200 SF short story anthologies by title, author and editor;

the 1976 chapbook Sciencefiction and Fantasy Pseudonyms, edited by Barry McGhan, listing 945 authors and the various pen names they used; and

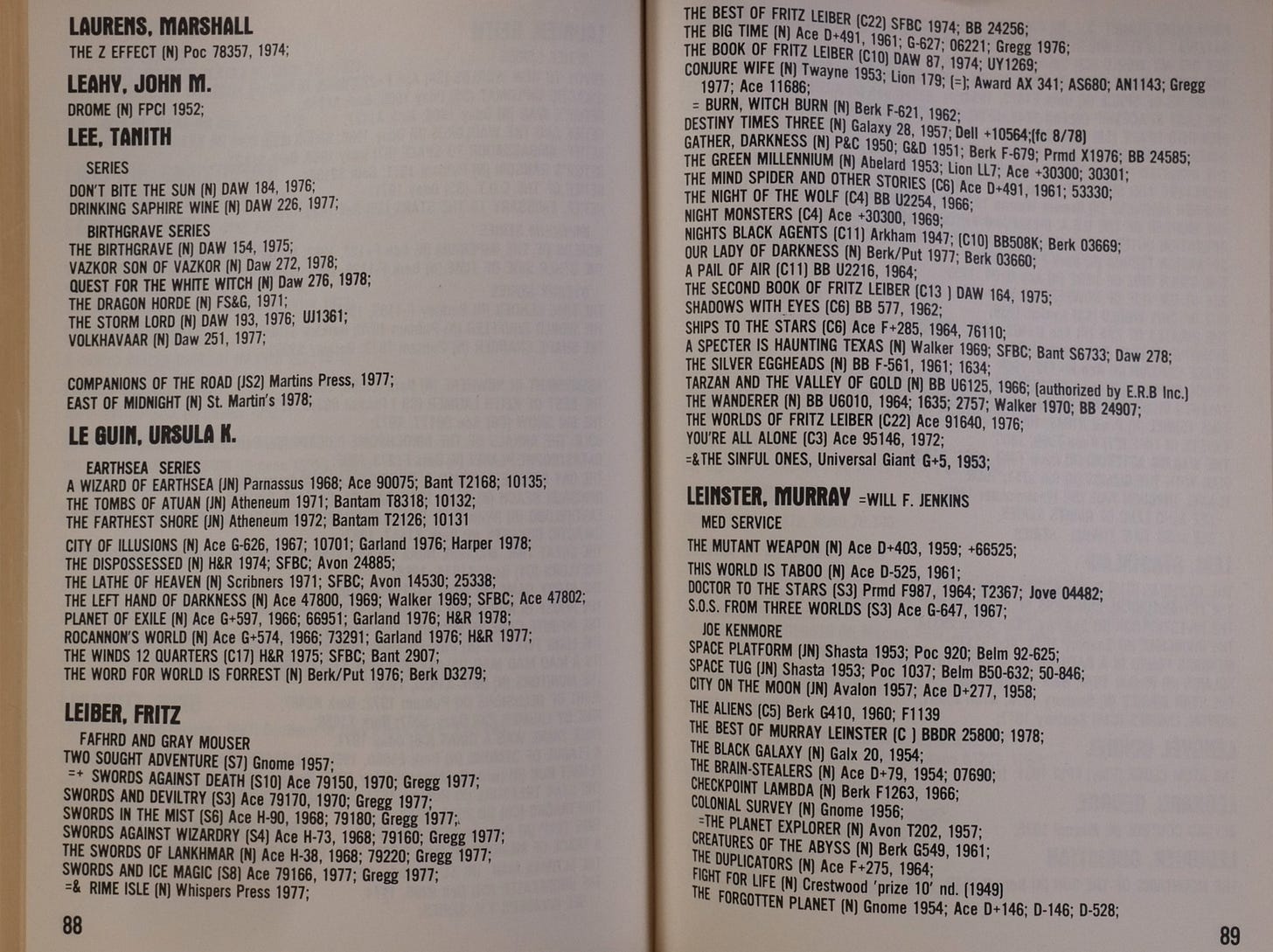

the 1978 self-published The Science Fiction and Heroic Fantasy Author Index, compiled by Stuart W. Wells III, that listed more than 1,000 authors and 5,000 novels and short fiction collections.

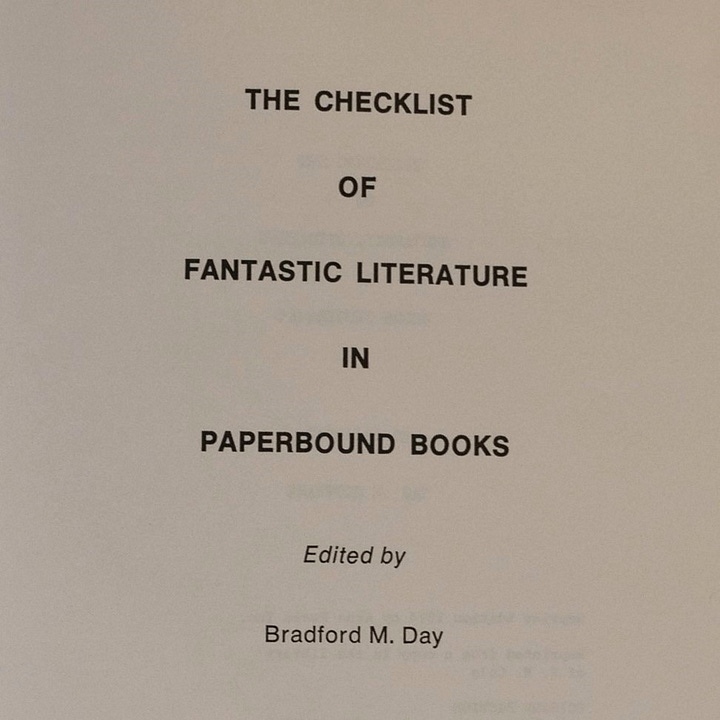

Efforts also were made to update Shasta’s Checklist, most notably by Bradford M. Day in his 1963 The Supplemental Checklist of Fantastic Literature and his 1965 The Checklist of Fantastic Literature in Paperbound Books (indexing paperback editions of SF novels, collections and anthologies)

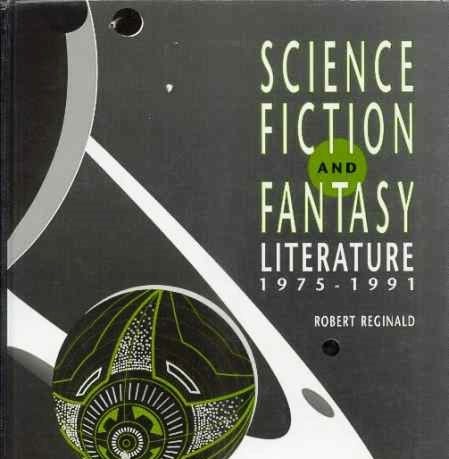

However, the most comprehensive effort to produce a definitive bibliography in the days before personal computers, word processors and spreadsheet data tables was by Michael R. Burgess, writing as Robert Reginald, who compiled Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature: A Checklist, 1700-1974. It was first published in 1979 and listed more than 15,000 titles. A 1992 supplement covering the years 1975-1991 added another 22,000 titles, and a revised and expanded edition was published in 2010.

Rare book dealers also began sharing their knowledge of how to identify first editions of collectible speculative fiction in:

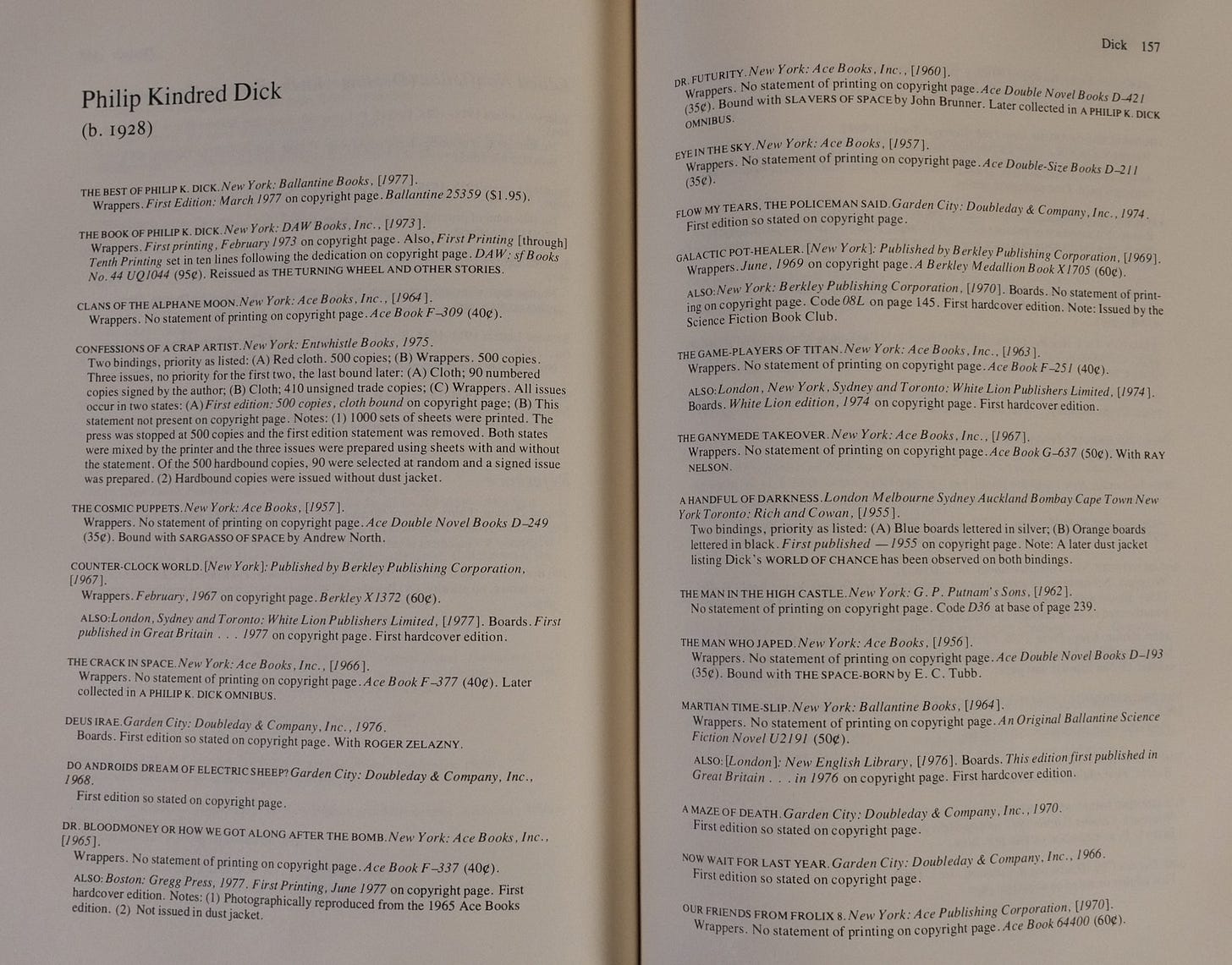

Science Fiction First Editions, by British bookseller and collector George Locke, self-published in 1978 in a signed, hardcover edition limited to 56 copies that focused on approximately 240 titles he considered noteworthy and collectible (it even includes price guides from 1978 for many titles); and

Science Fiction and Fantasy Authors: A Bibliography of First Printings of Their Fiction, by American bookseller L.W. Currey with assistance from David G. Hartwell, published in hardcover in 1979 that describes identification points for around 6,200 editions of the major works of 215 science fiction and fantasy authors. The Currey guide has been updated and expanded substantially over the years and remains a key reference manual for booksellers and collectors alike.

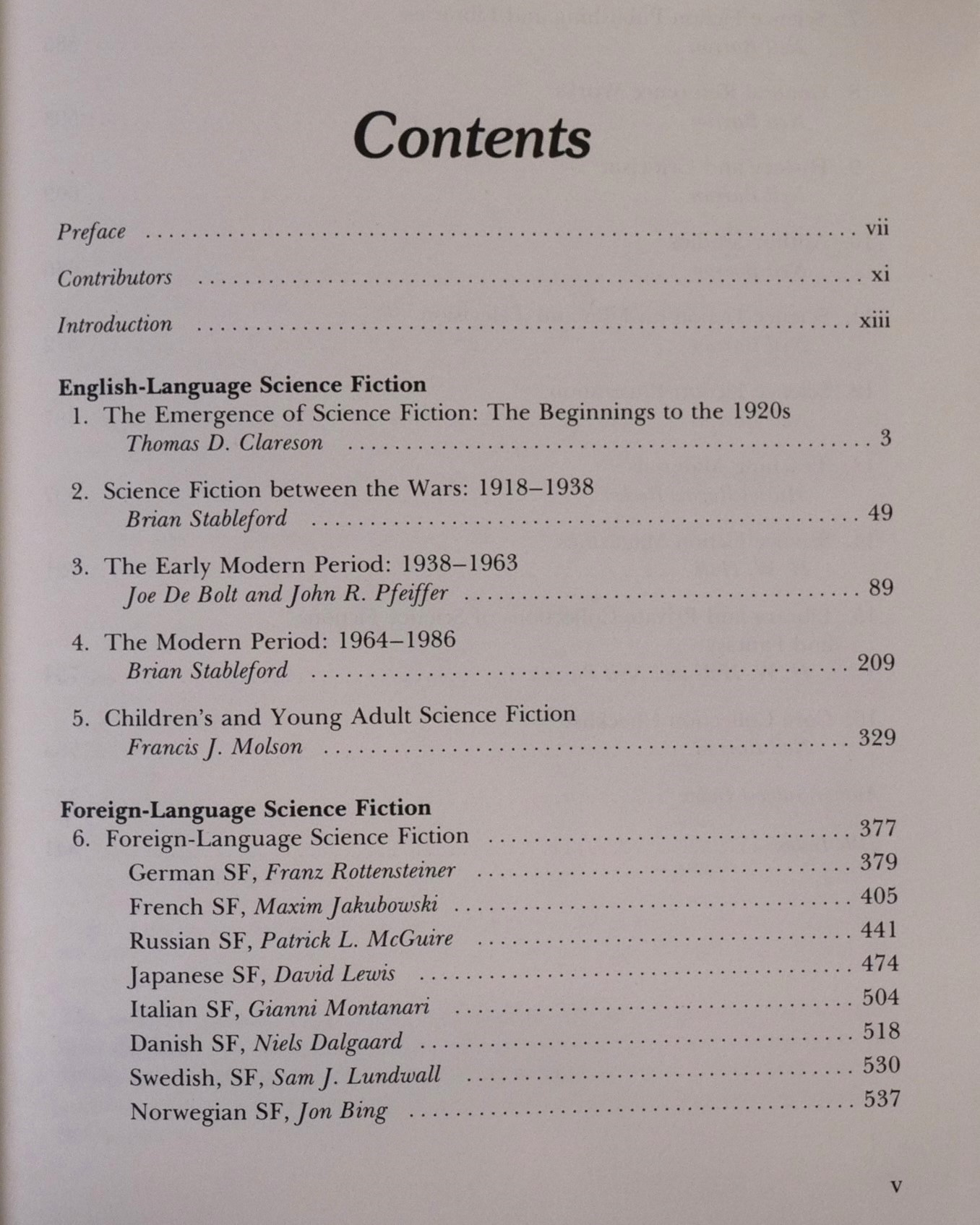

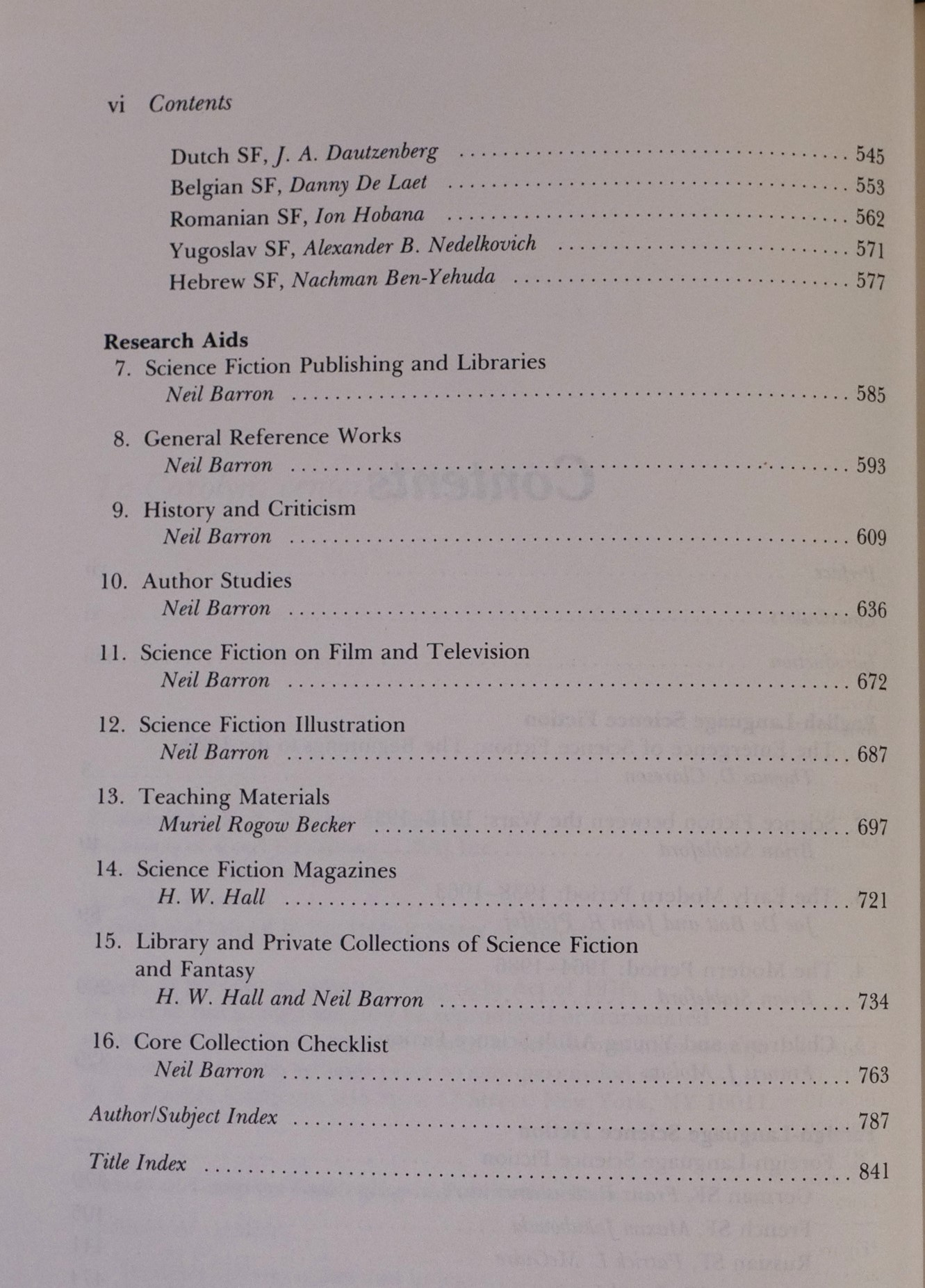

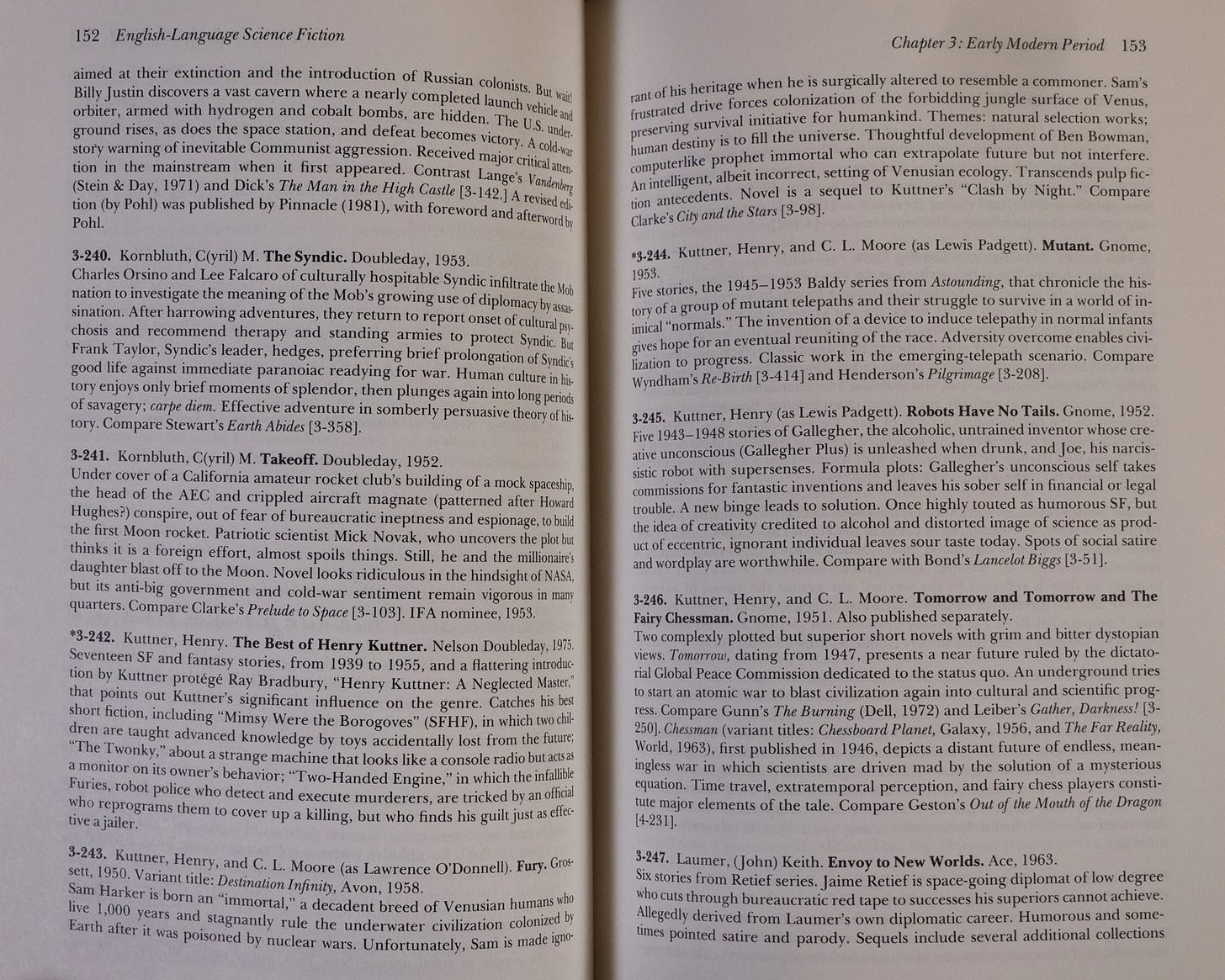

Then there appeared Anatomy of Wonder, edited by Neil Barron. It was first published in 1976 and has been revised and expanded four times, most recently in 2004. The 1987 third edition, which I have, spotlights more than 1,200 authors and 3,000 titles, including significant foreign-language science fiction works. It gives brief publication information for each title, but focuses more on providing single-paragraph critiques of a title’s artistic and historical significance. It was designed for collectors and researchers to use in tandem with the Reginald and Currey bibliographies.

Anatomy of Wonder also includes useful bibliographies of many SF reference guides, author and illustrator biographies and studies, and noteworthy university and library collections of science fiction-related material.

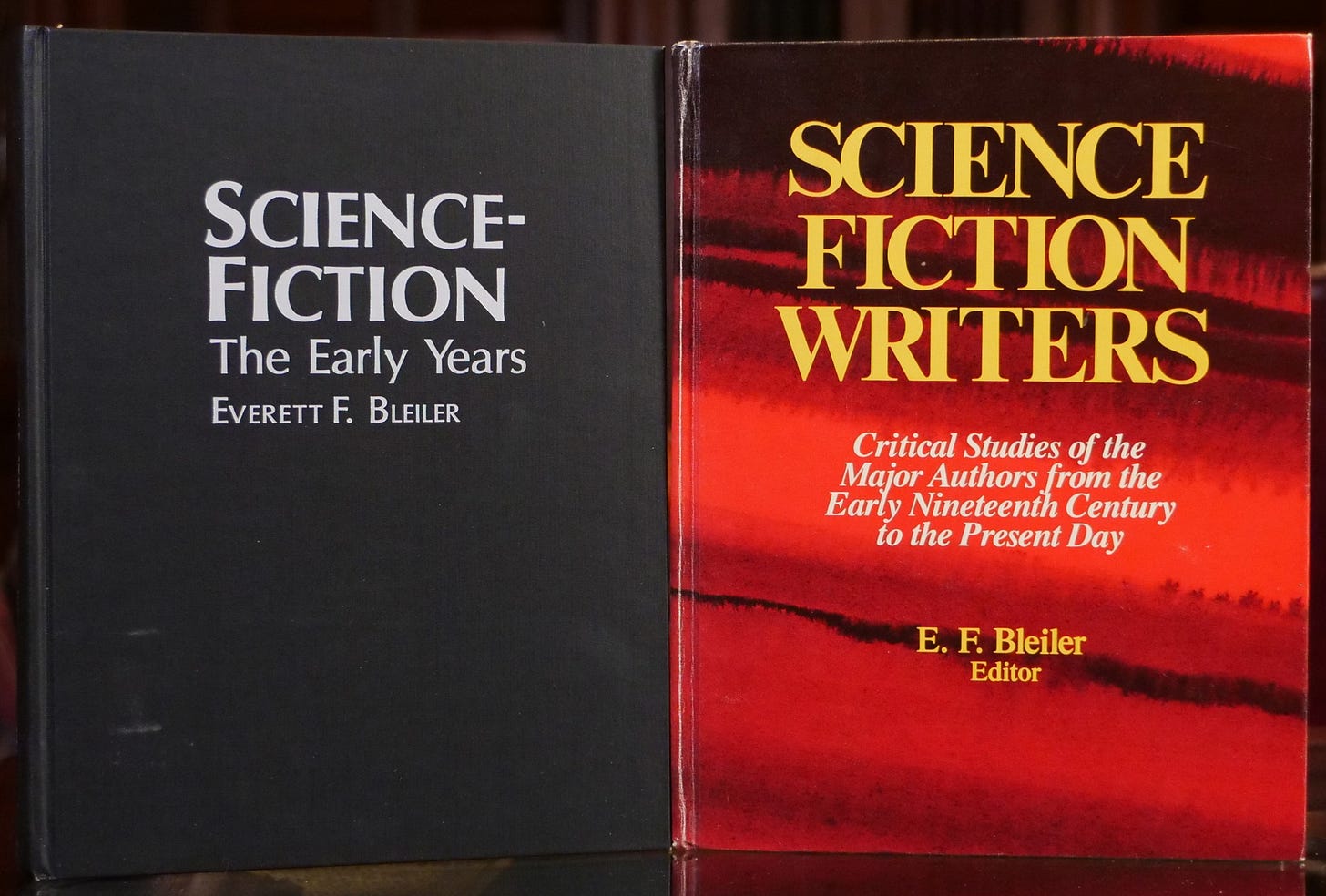

In a similar vein, Everett Bleiler produced Science Fiction: The Early Years in 1990 containing detailed descriptions and critiques of more than 3,000 SF stories published prior to 1930. He produced a second volume, subtitled The Gernsback Years, in 1998 covering the early years of SF pulp magazines in the 1930s. Bleiler also produced insightful biographical and critical accounts of many speculative fiction authors in 1982’s Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day and 1985’s Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. In 1983, he also published The Guide to Supernatural Fiction, a 735-page volume containing brief reviews of hundreds of works of horror and fantastical fiction.

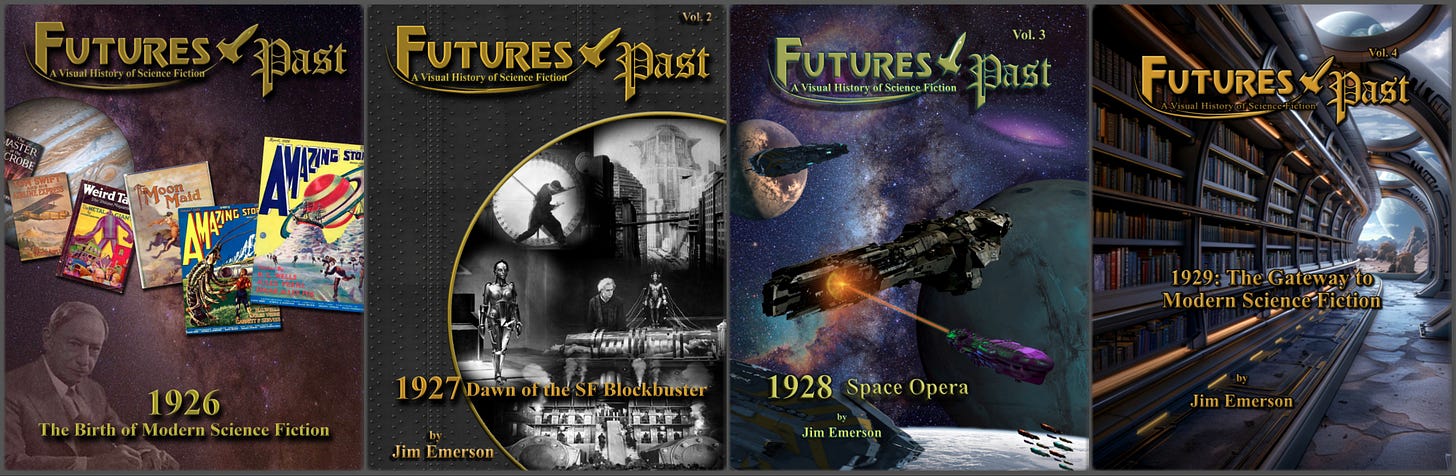

Another very impressive information resource is a planned 50-volume, comprehensive visual history of science fiction titled Futures Past compiled by longtime SF enthusiast and professional librarian Jim Emerson. When completed, it will cover the period 1926-1975 with a separate volume for each year. As of early 2025, the first four volumes (1926-1929) have been published and can be found at sfhistory.net. Its unique pairing of detailed information about SF publications and hundreds of photos and other images makes it a valuable resource. As more volumes are published, its value to SF fans and collectors will also grow.

Each of the bibliographies I’ve discussed is a remarkable accomplishment, requiring countless hours of toil and tedium to hand-compile, error-check and format the contents of every page. In editions produced before the personal computer age, entire pages often had to be retyped just to add a single new entry or to correct an error. Unfortunately, the small print runs of most bibliographies meant that few people ever had the opportunity to benefit from them.

This makes ISFDB’s online resources an incredible value, putting nearly all of the information contained in those earlier bibliographies at the fingertips of anyone with an internet connection. It lacks the plot summaries and critiques of individual titles found in Anatomy of Wonder and in Bleiler’s later cataloguing efforts from the 1980s and ‘90s, but almost everything else is contained in the site’s searchable database. I can’t imagine the enormous undertaking that must have been required to convert a hodgepodge of paper-based reference guides to a single, digital database. I’m extremely glad they did it, though.

Some other useful online information resources about the science fiction genre include Galactic Central, Fancyclopedia 3, and The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.