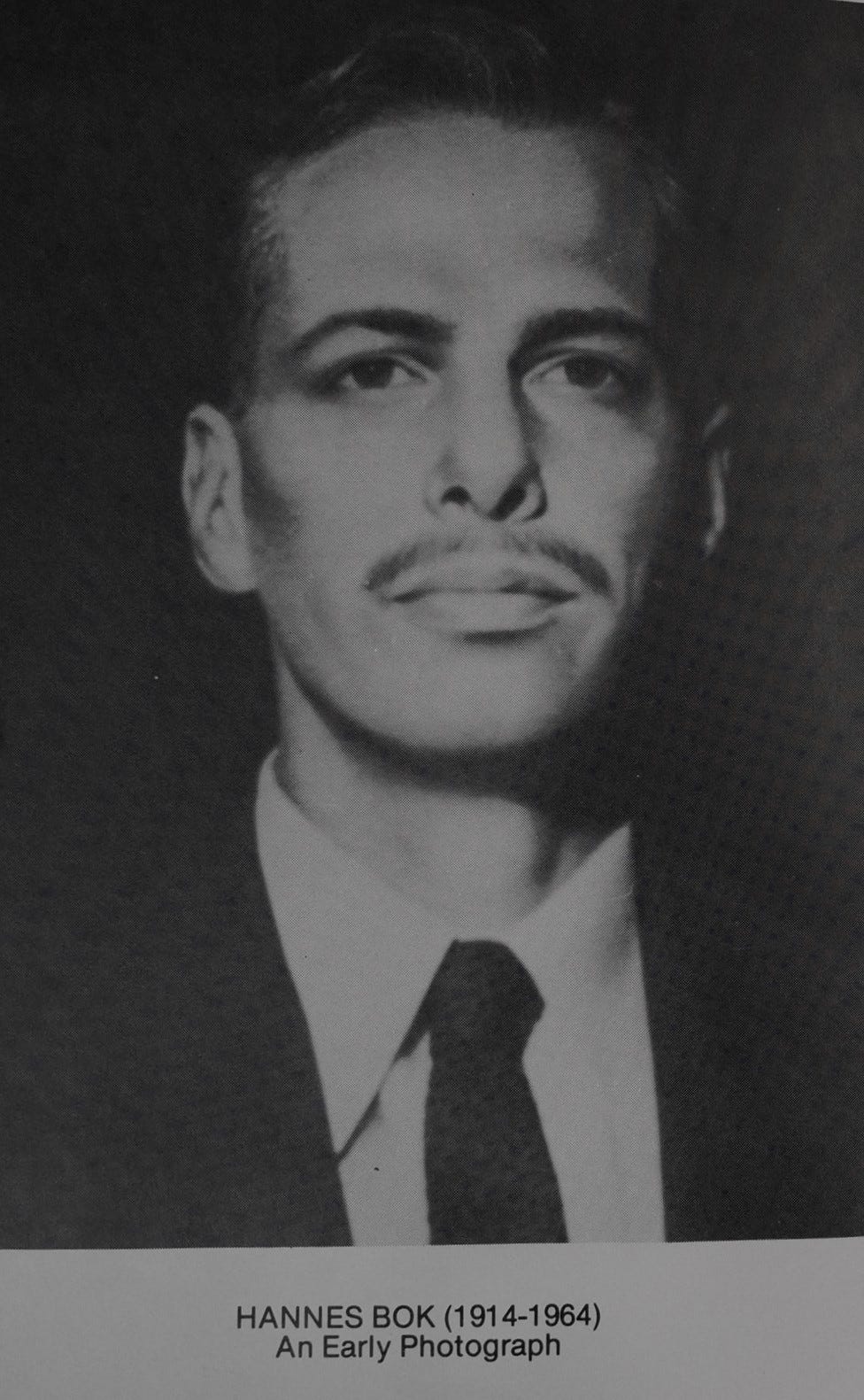

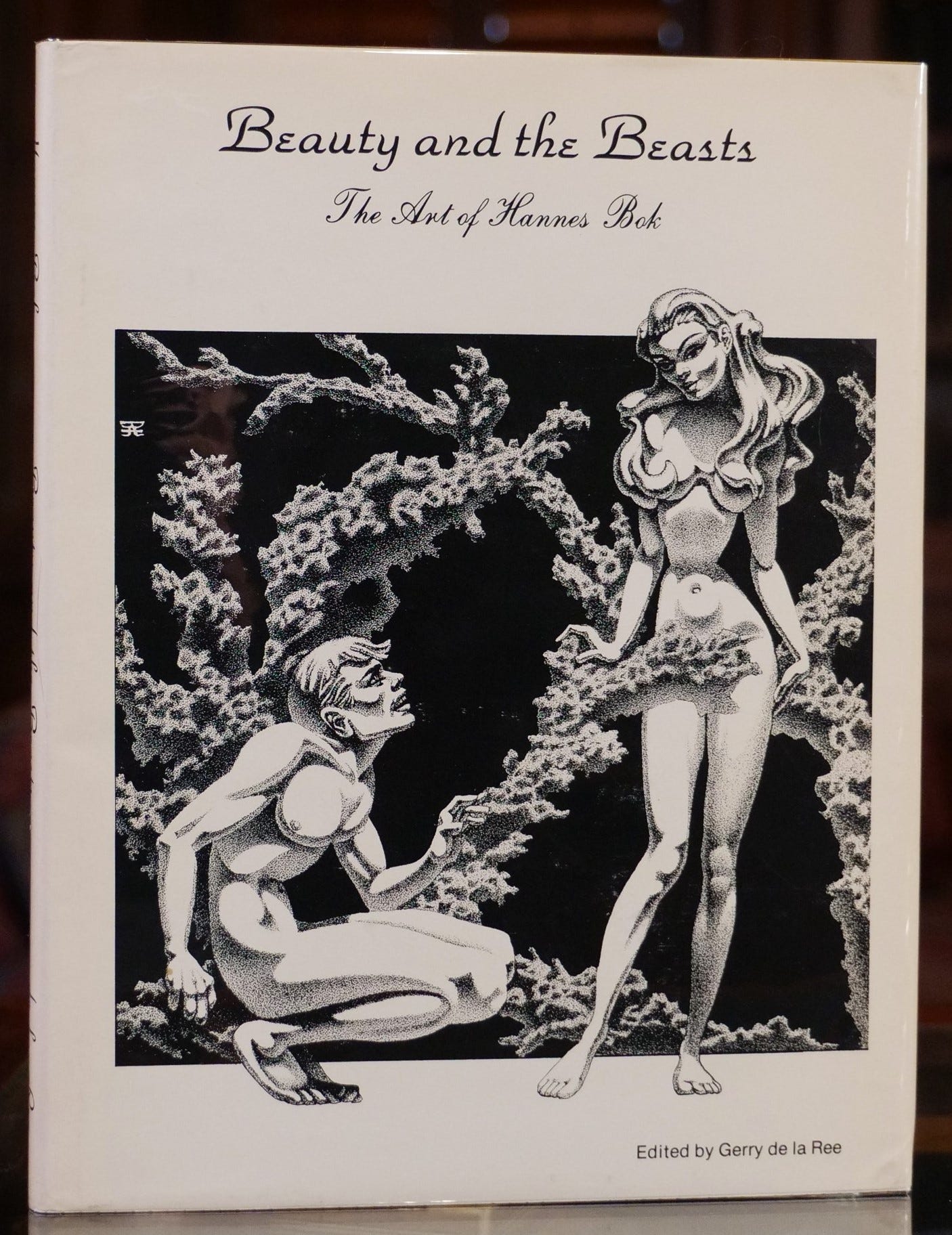

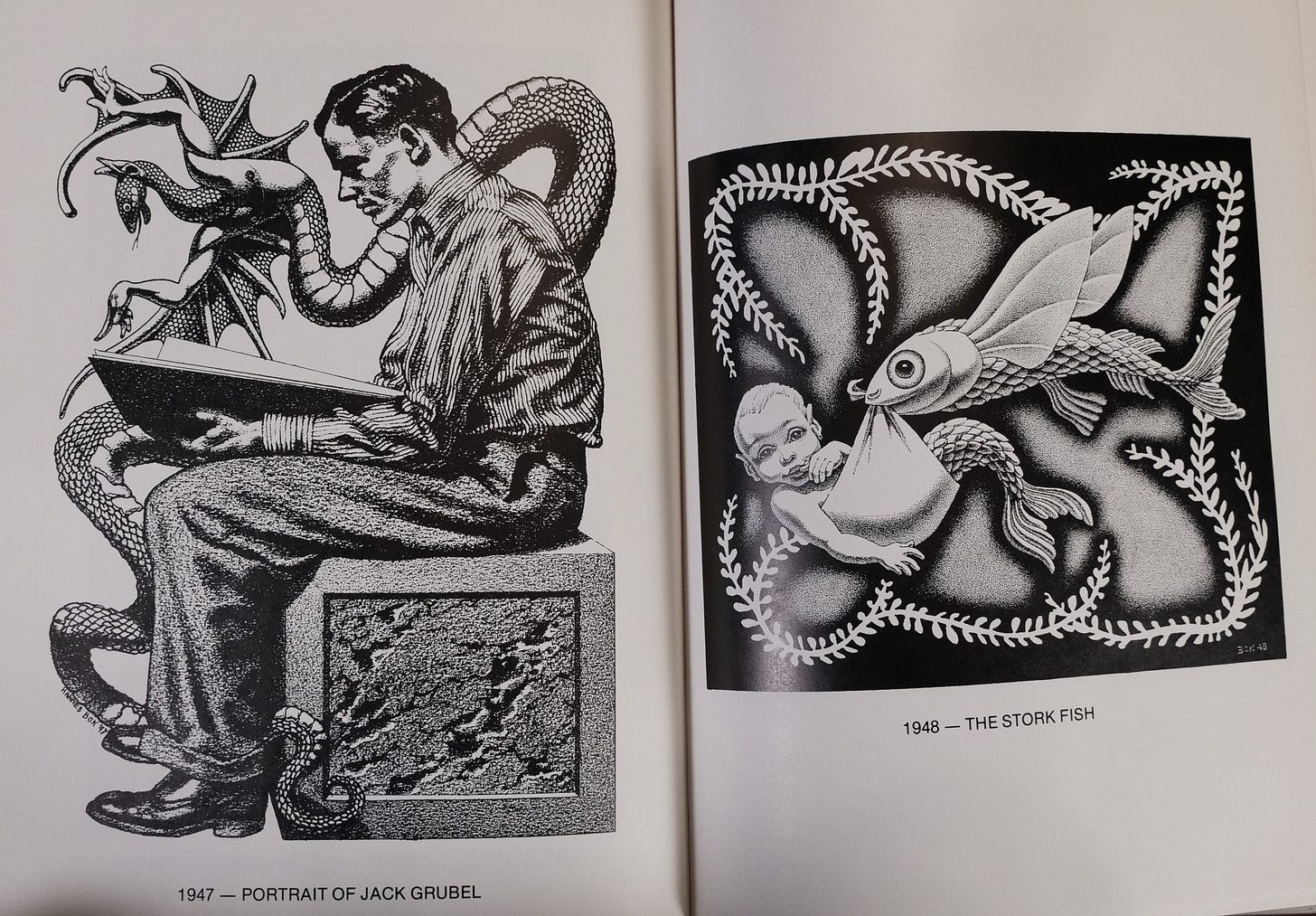

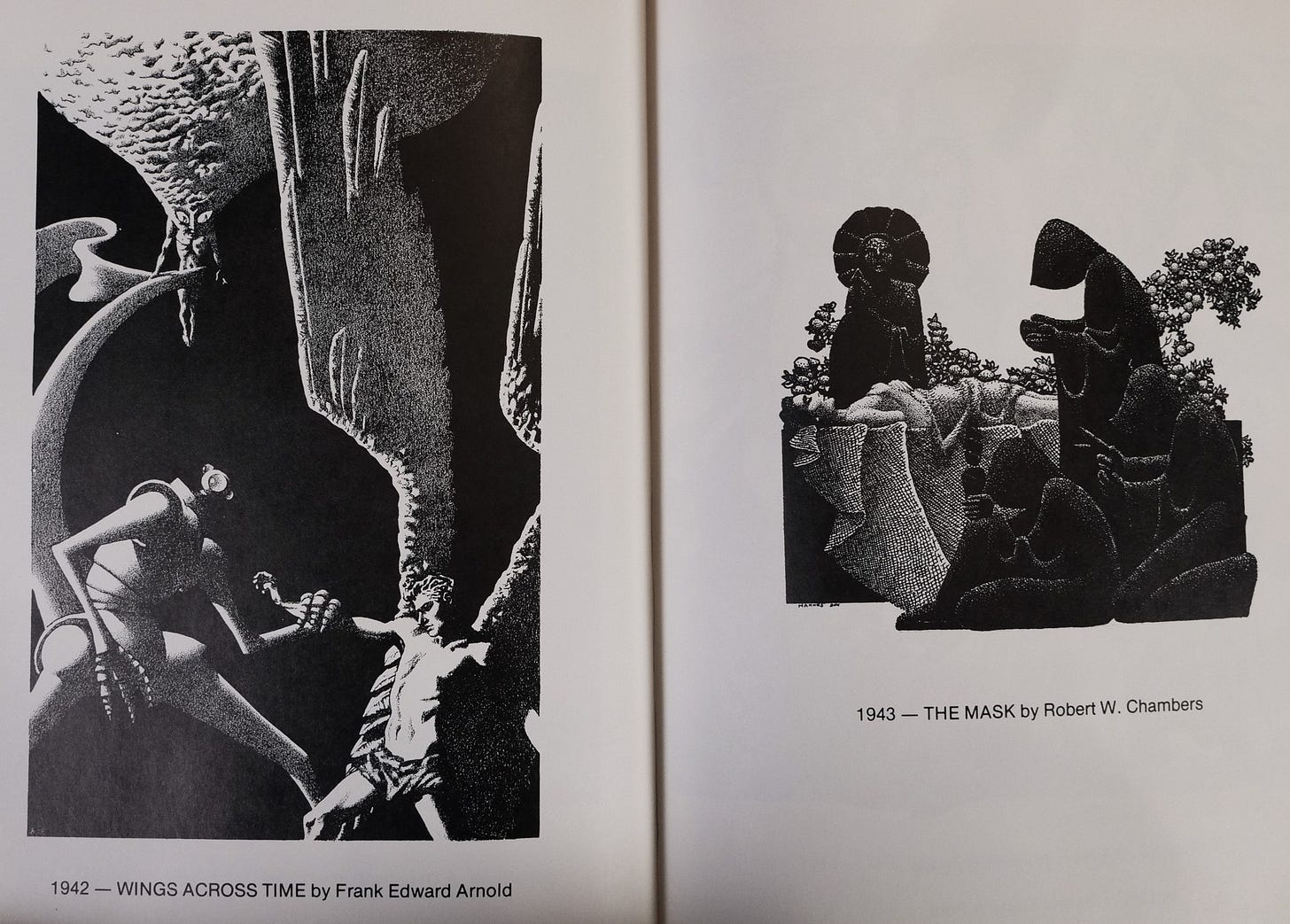

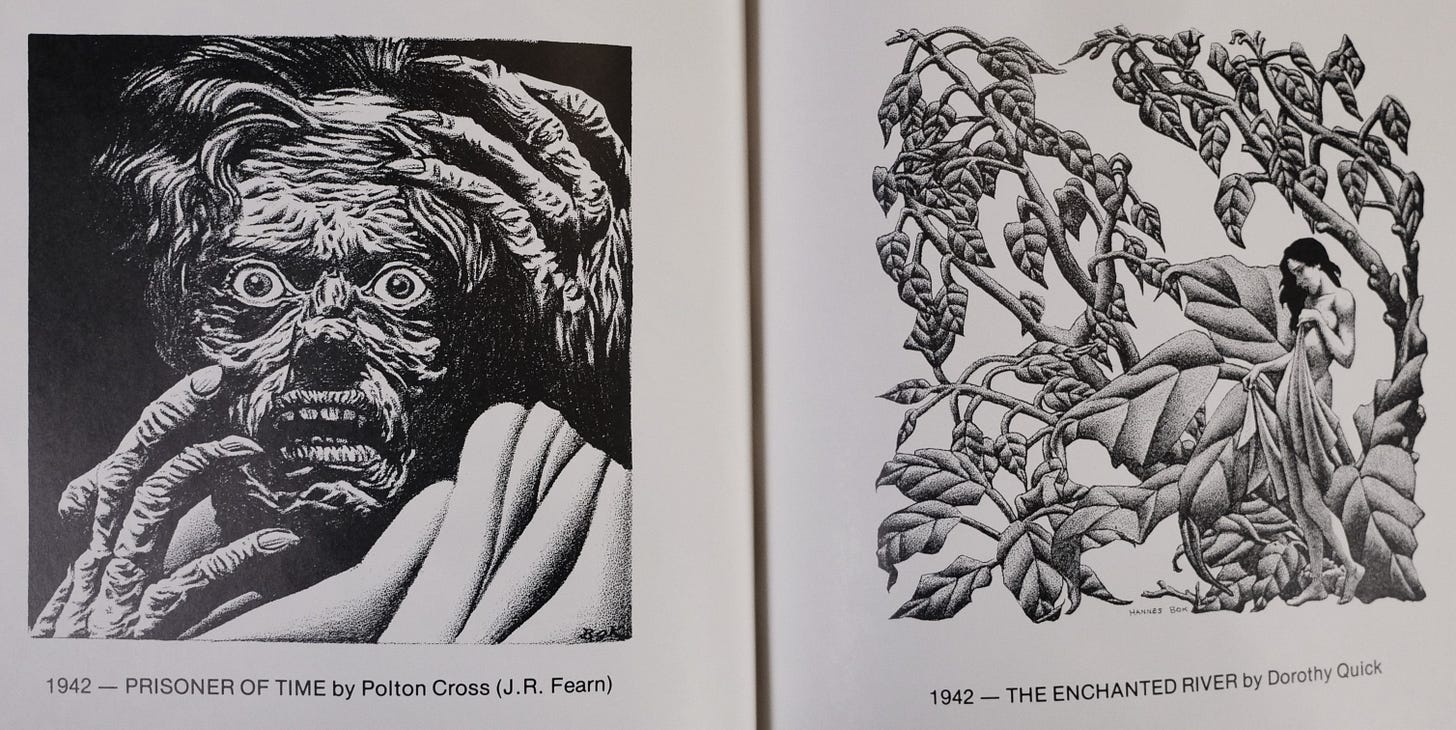

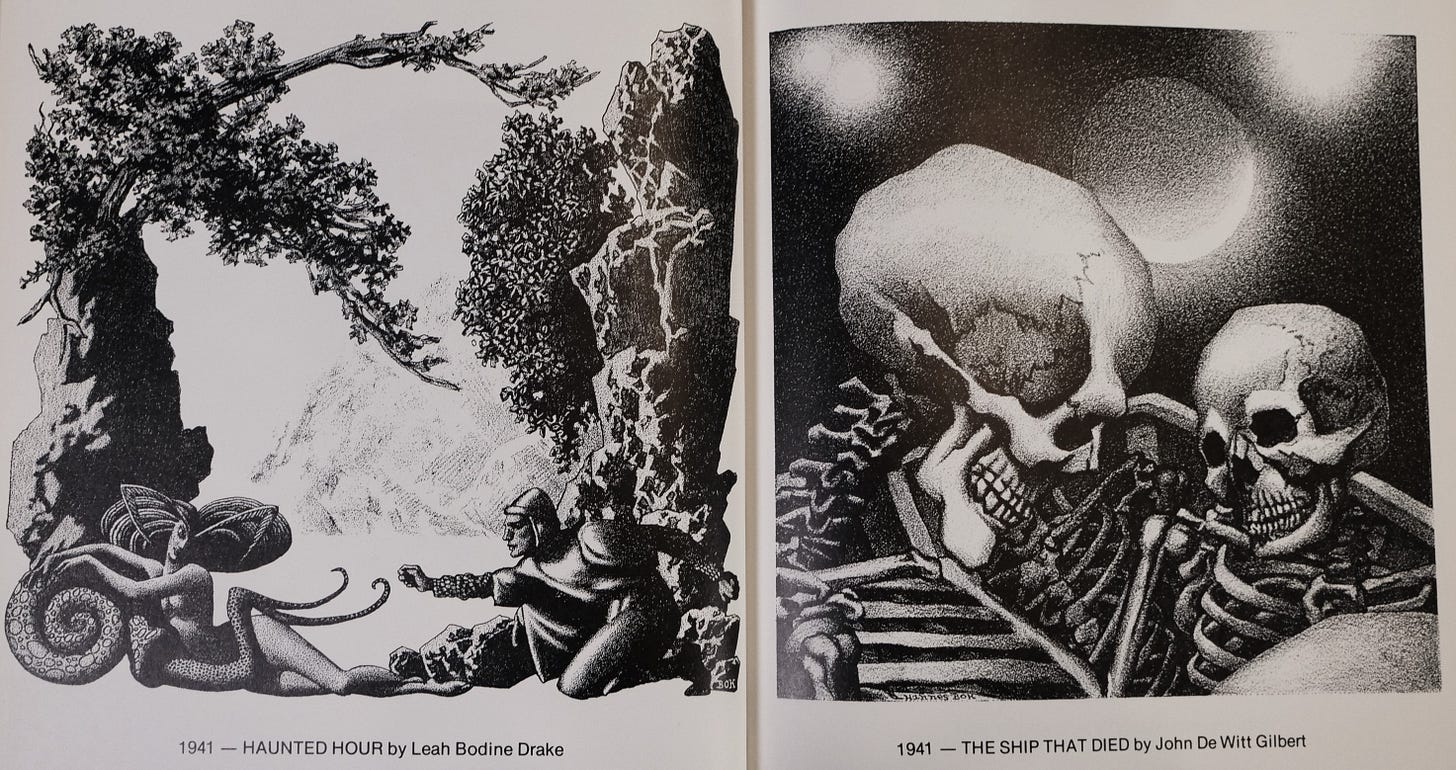

Hannes Bok is one of my favorite illustrators. He’s not a household name today, but to readers of science fiction, fantasy and horror stories in the 1940s and ‘50s, he was one of a handful of artists such as Virgil Finlay, Ed Emshwiller, Frank Kelly Freas and Edd Cartier, who were considered royalty.

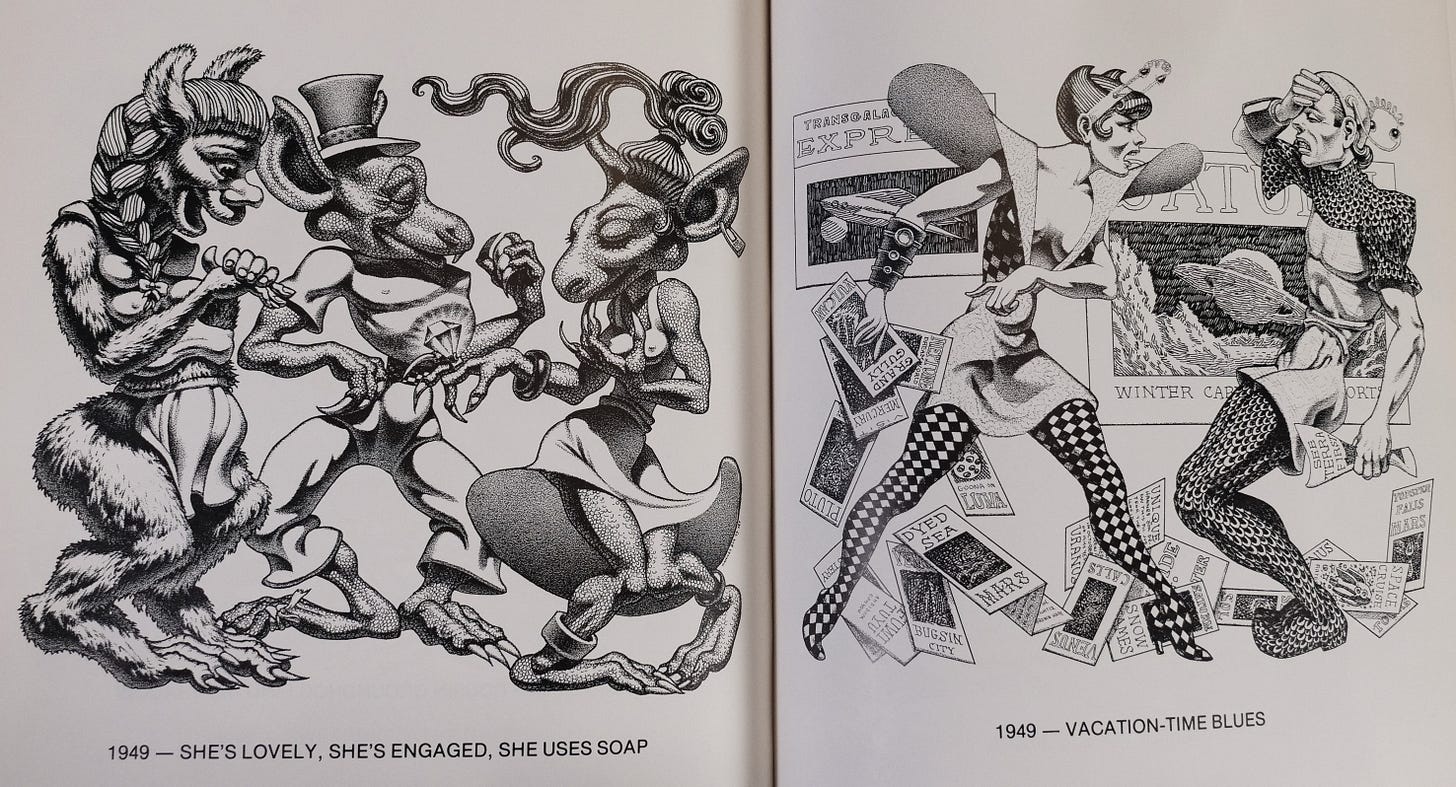

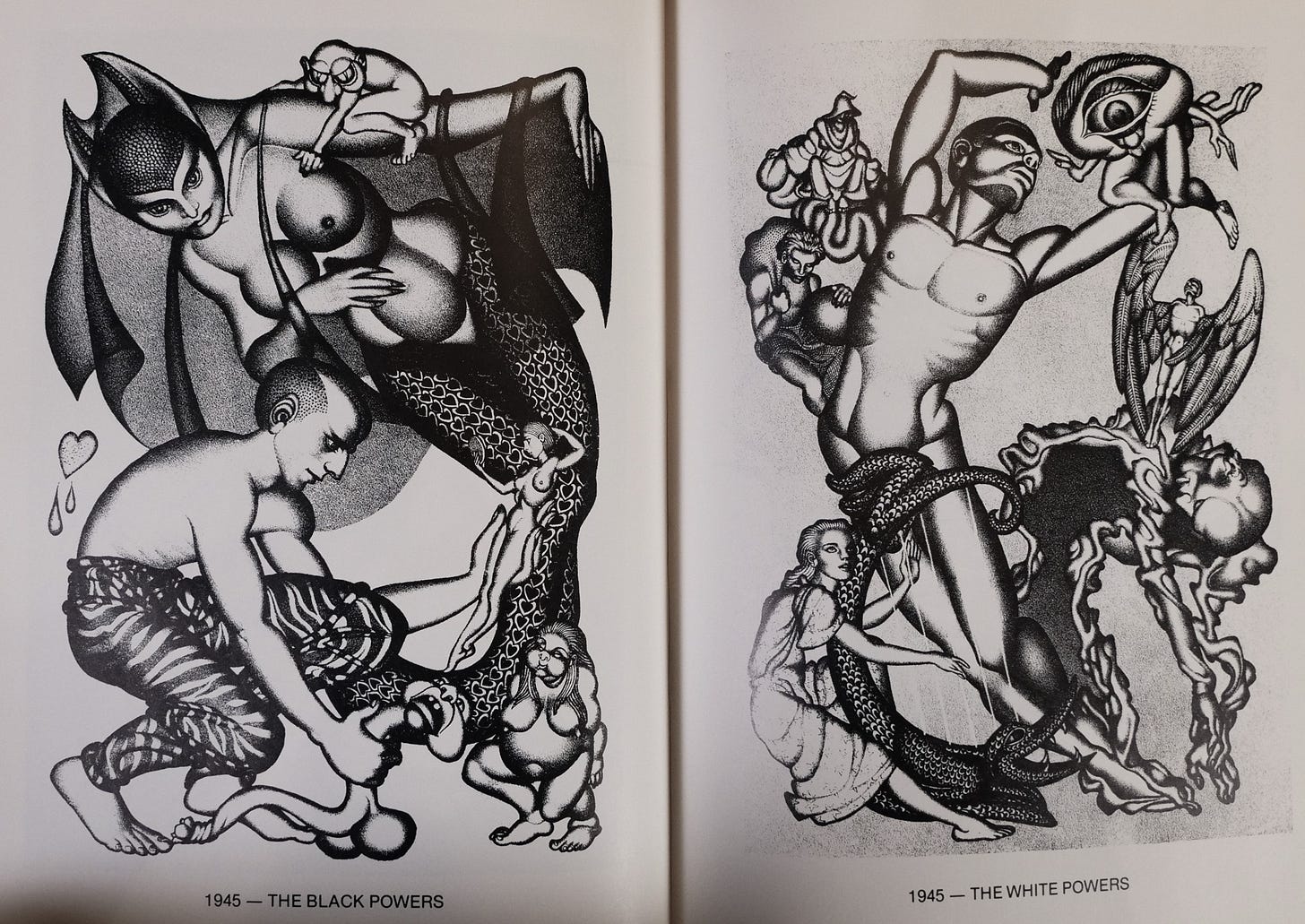

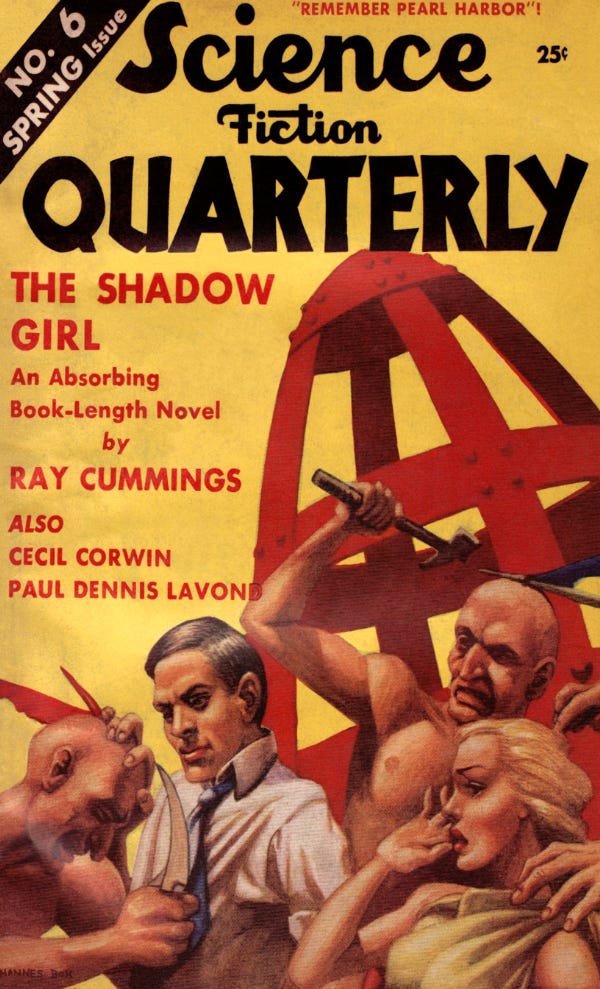

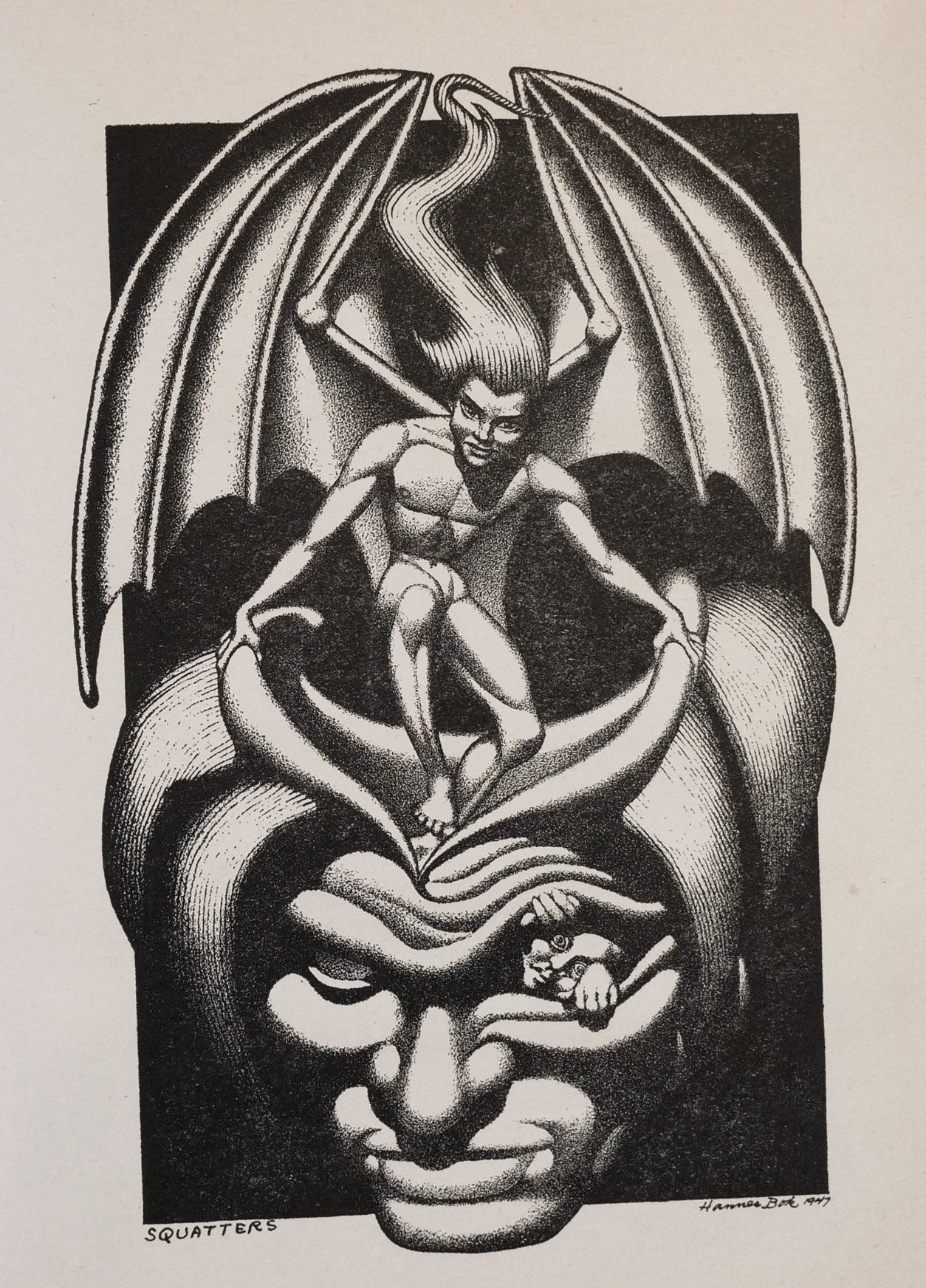

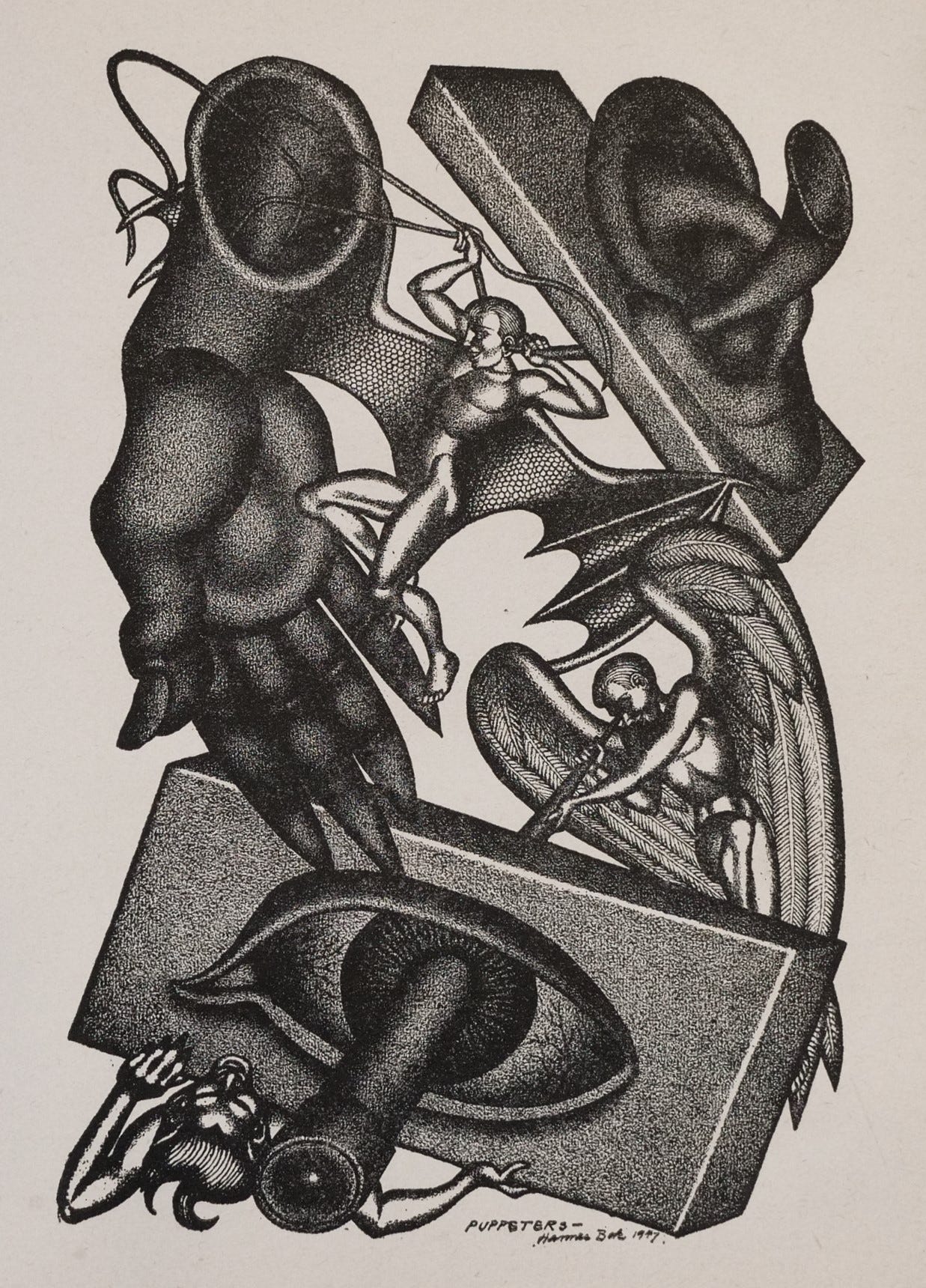

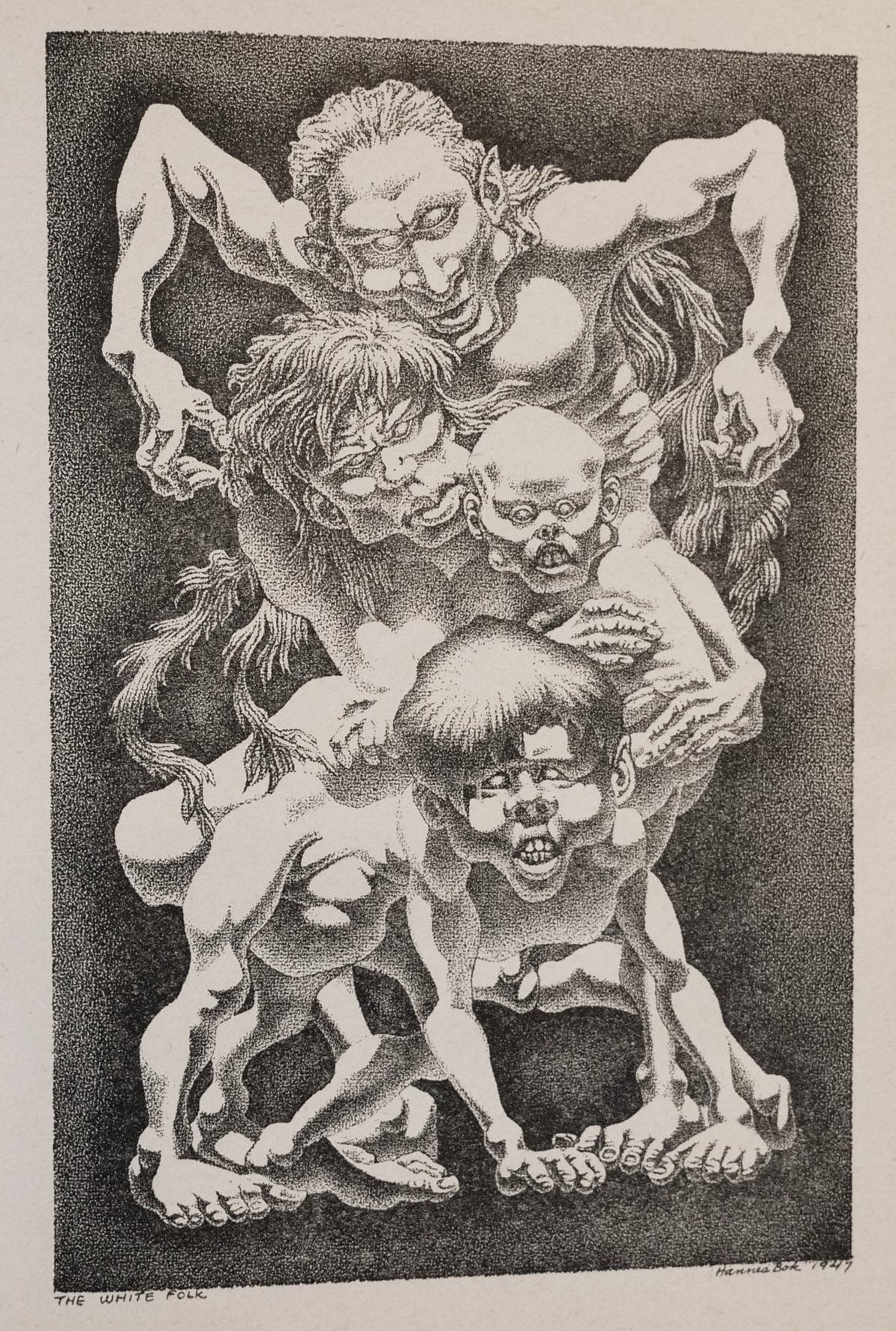

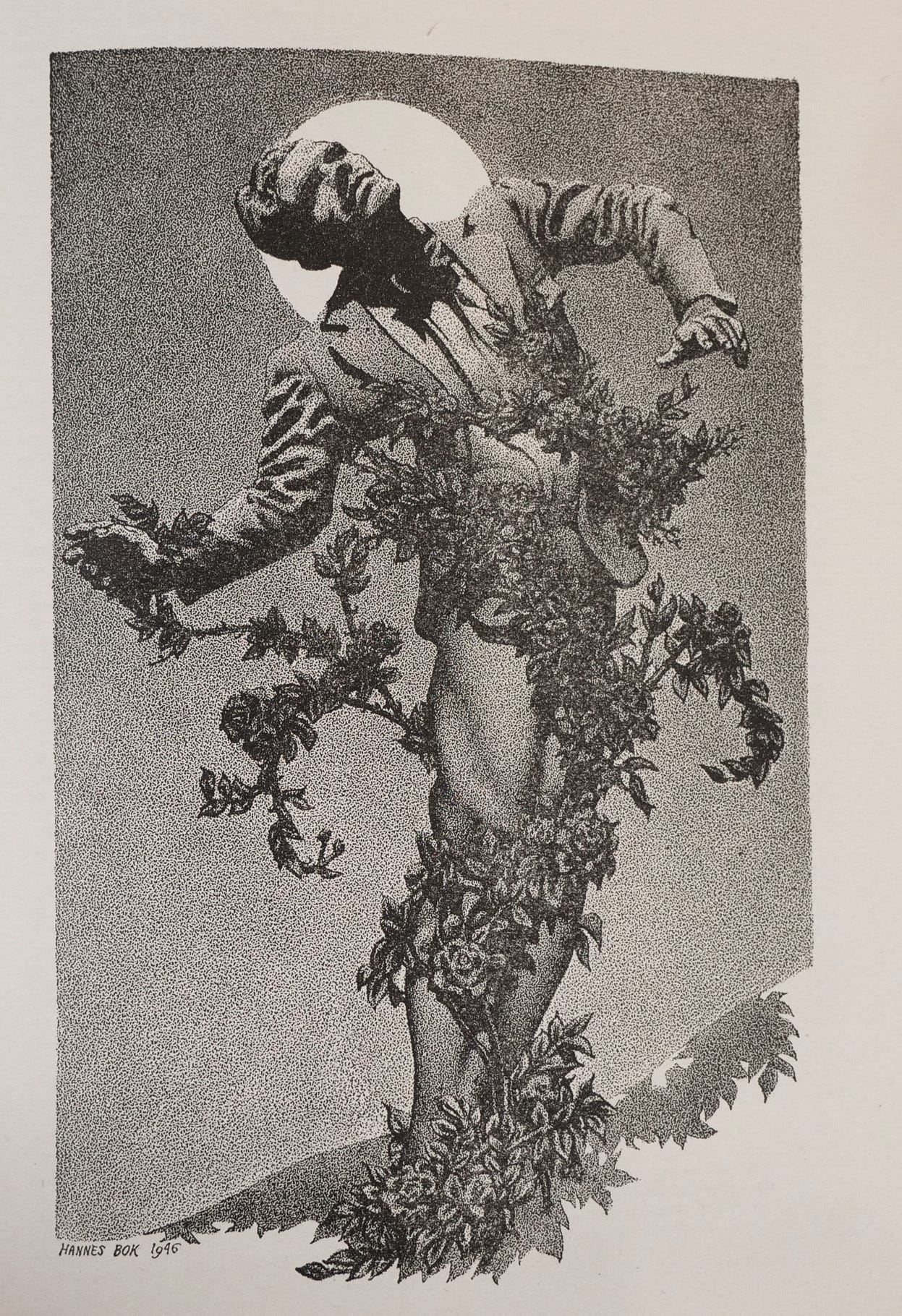

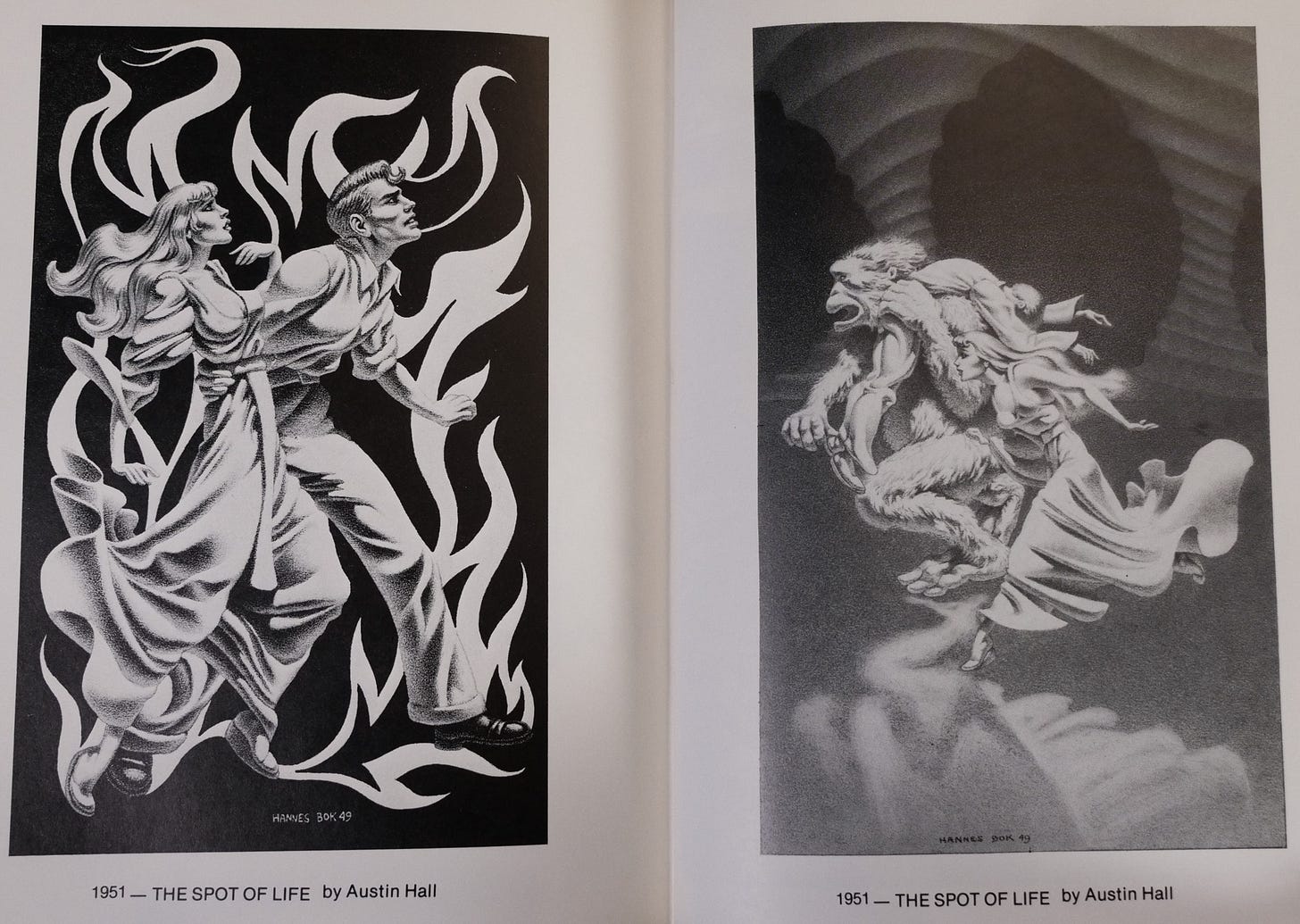

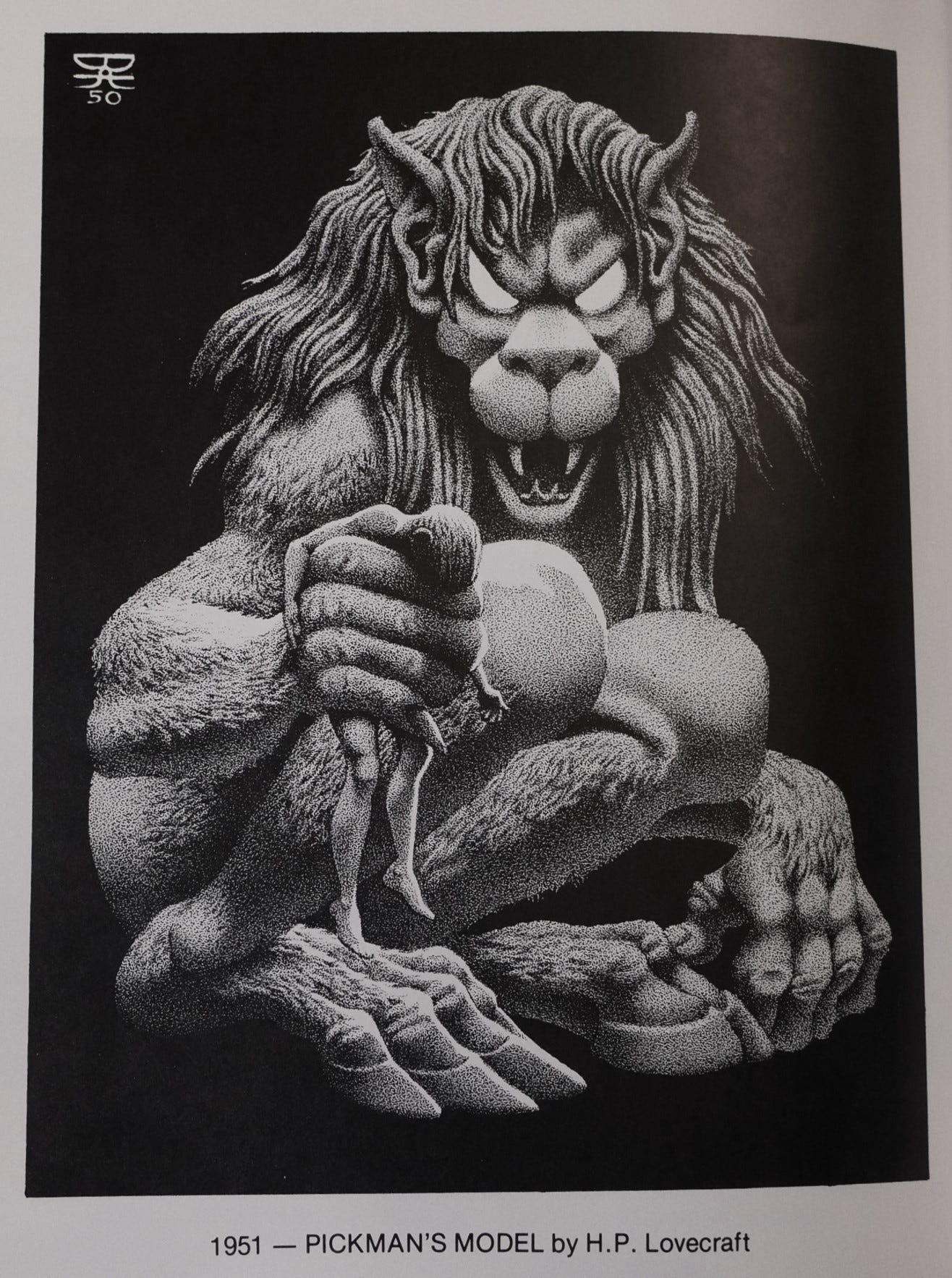

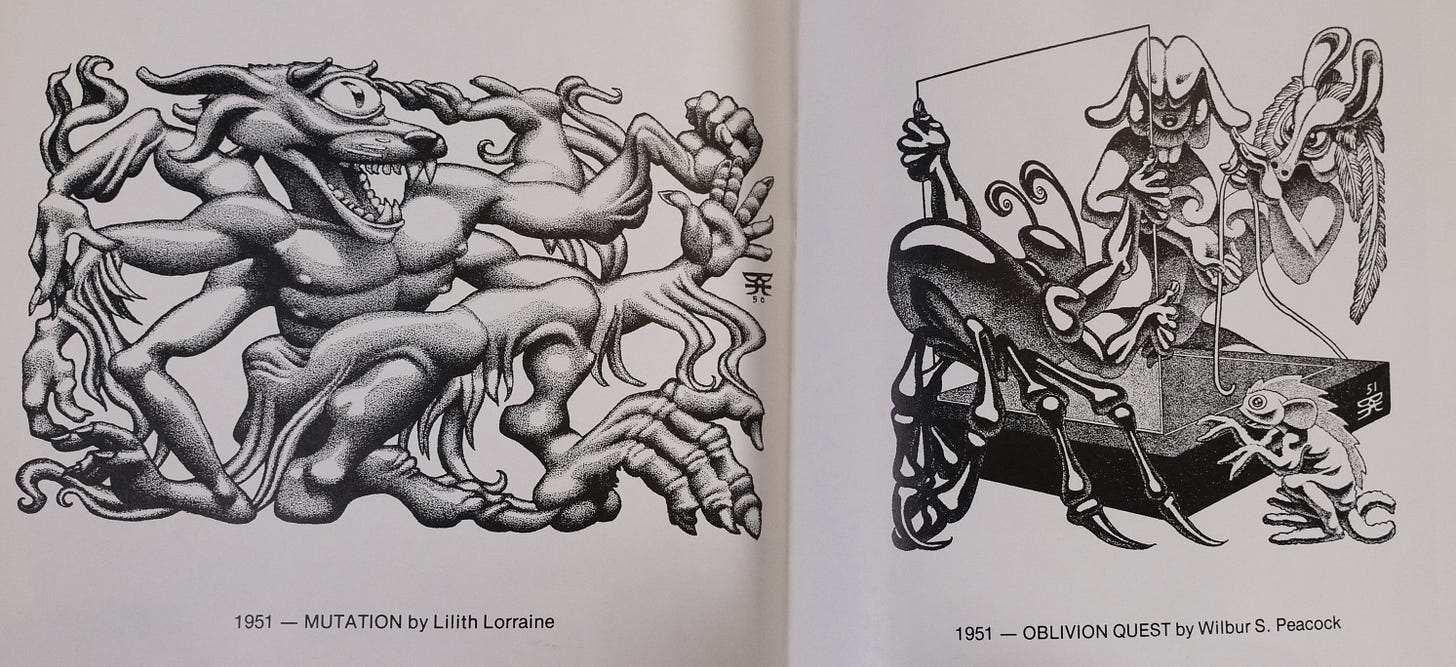

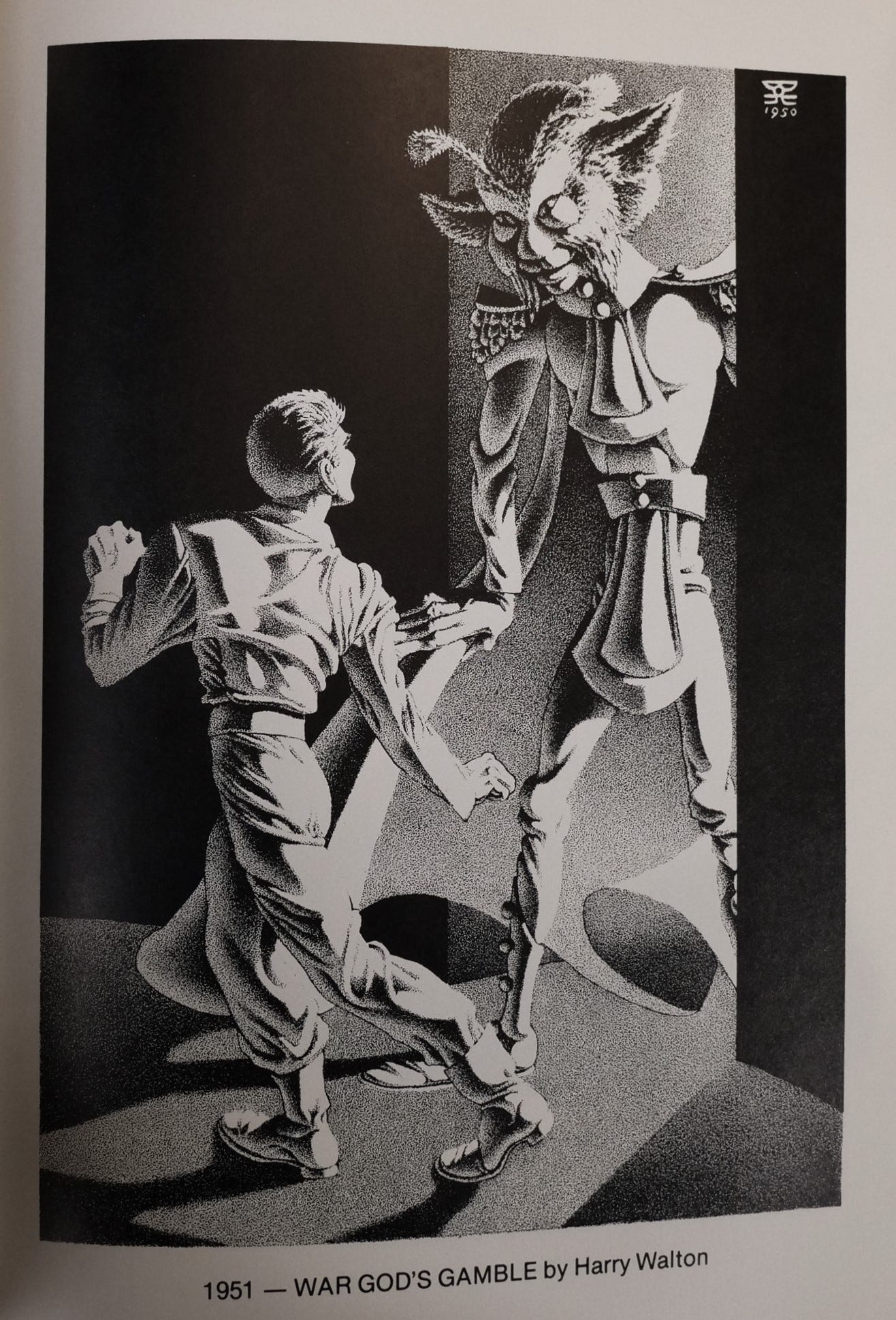

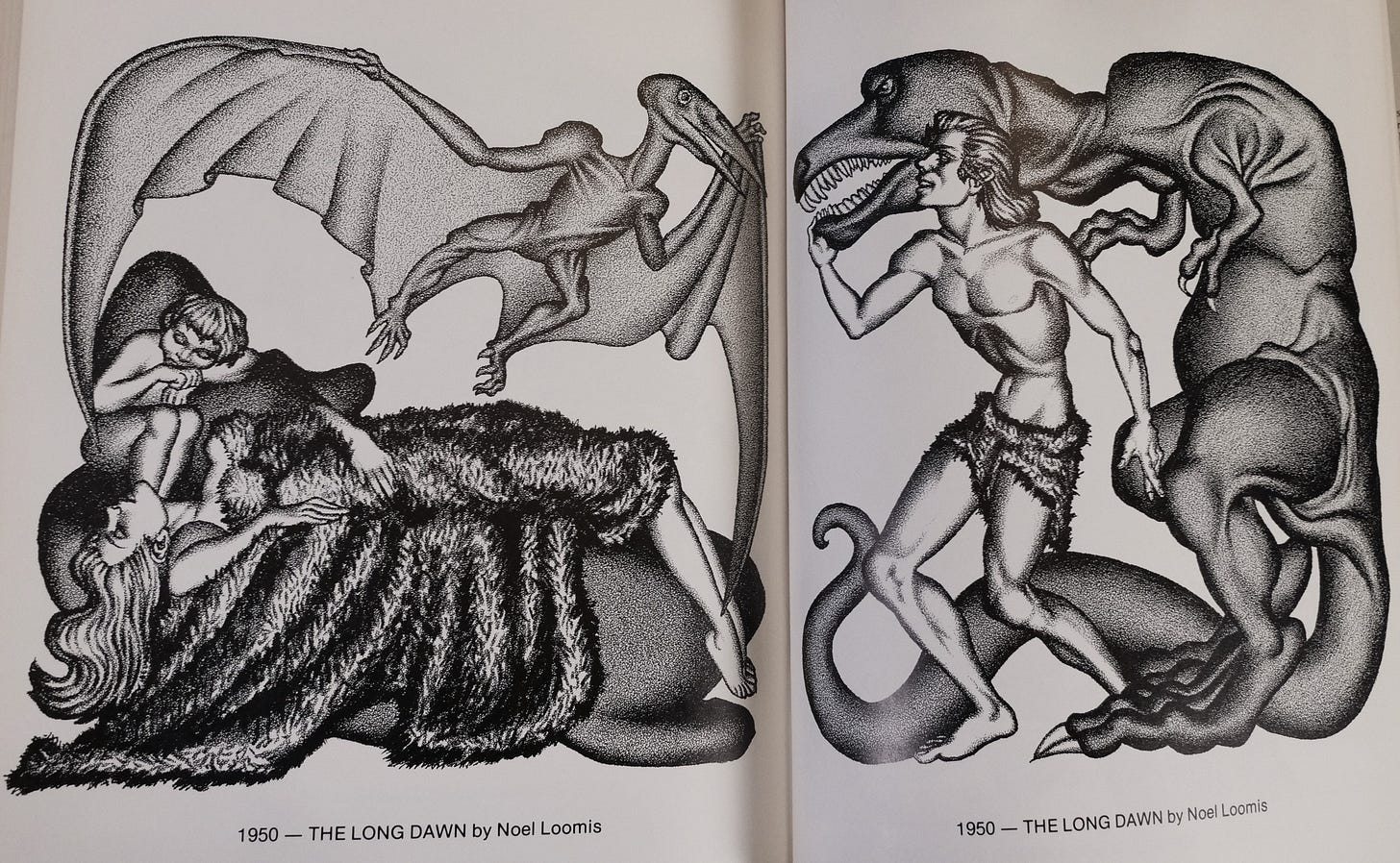

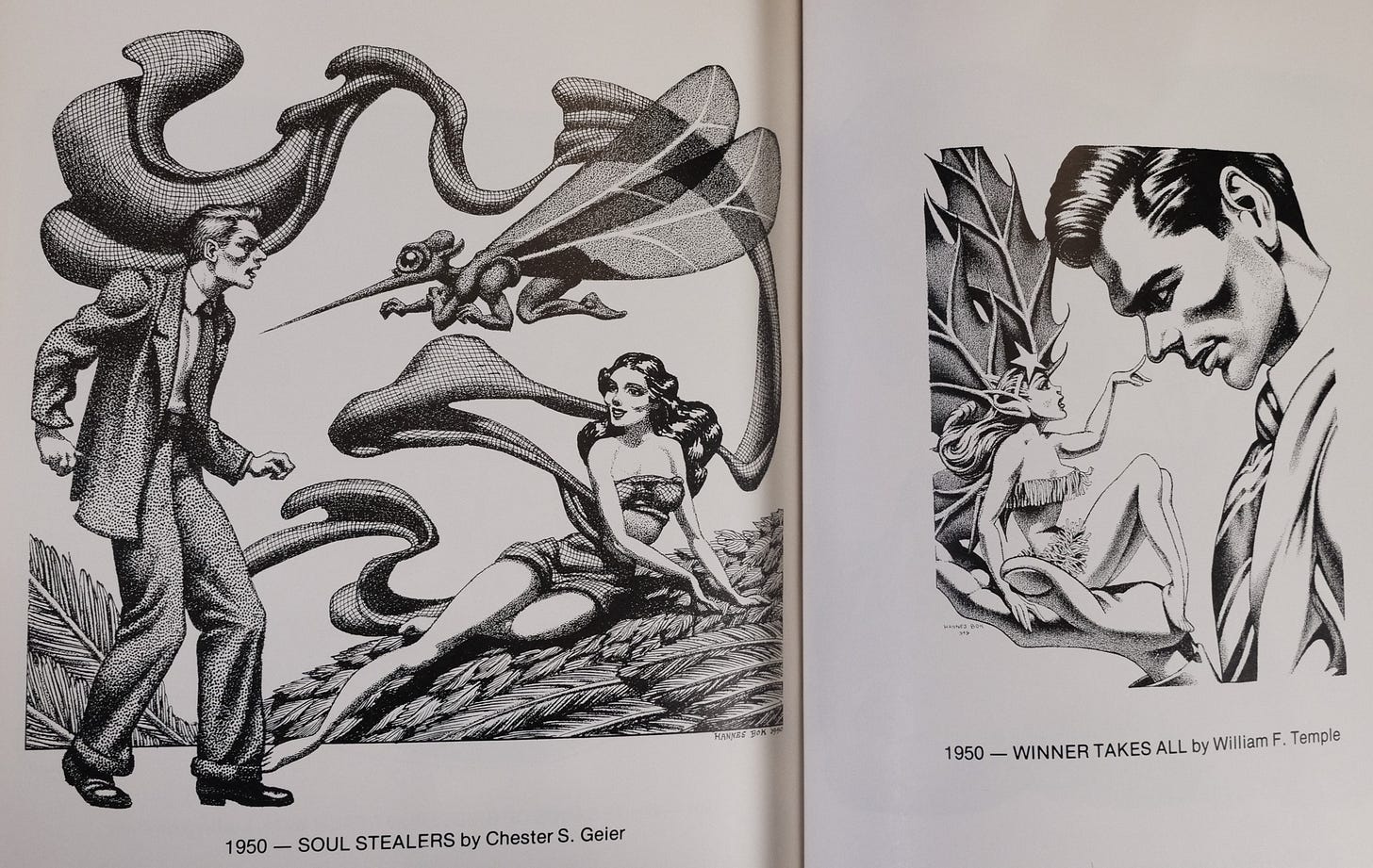

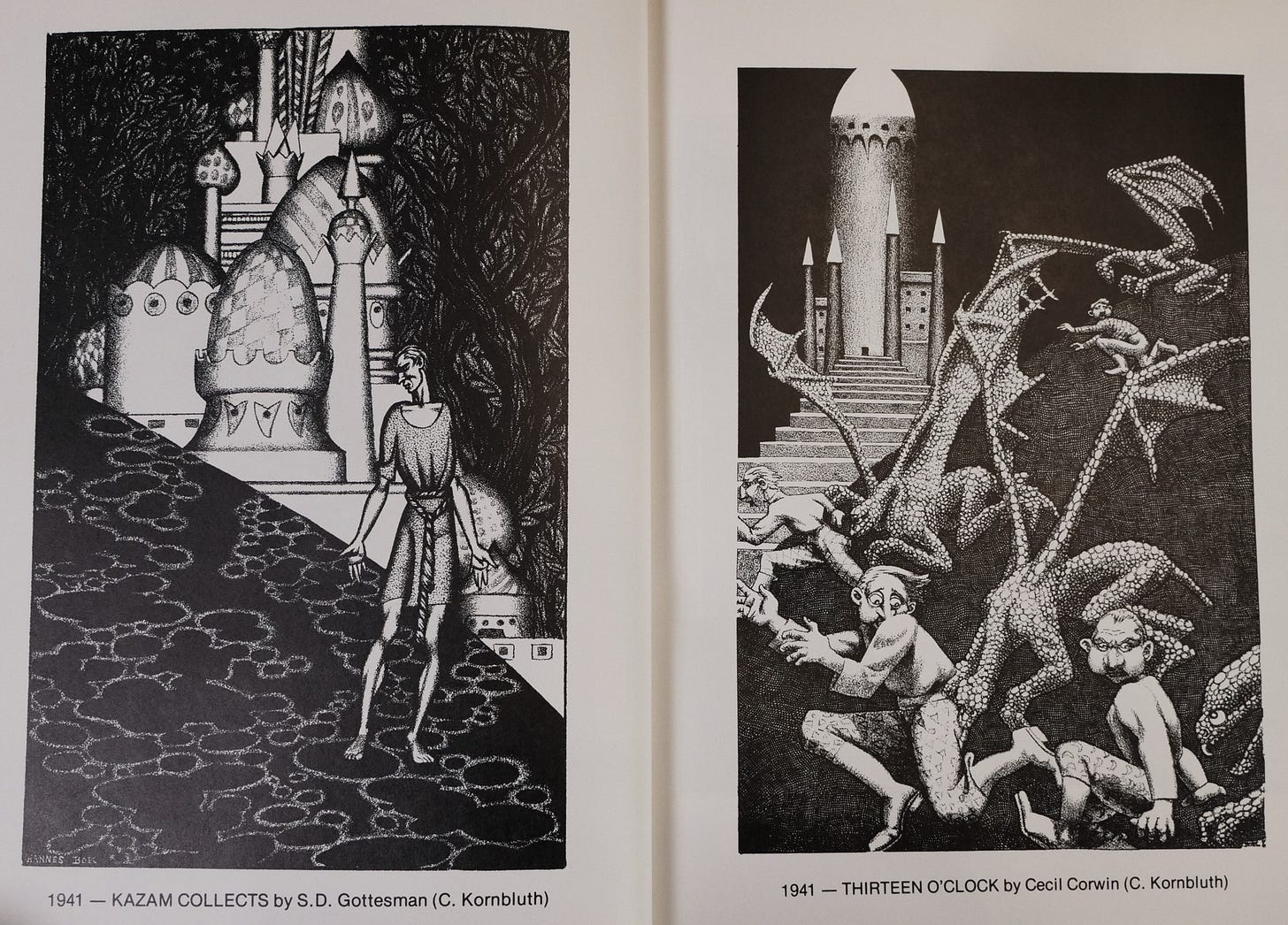

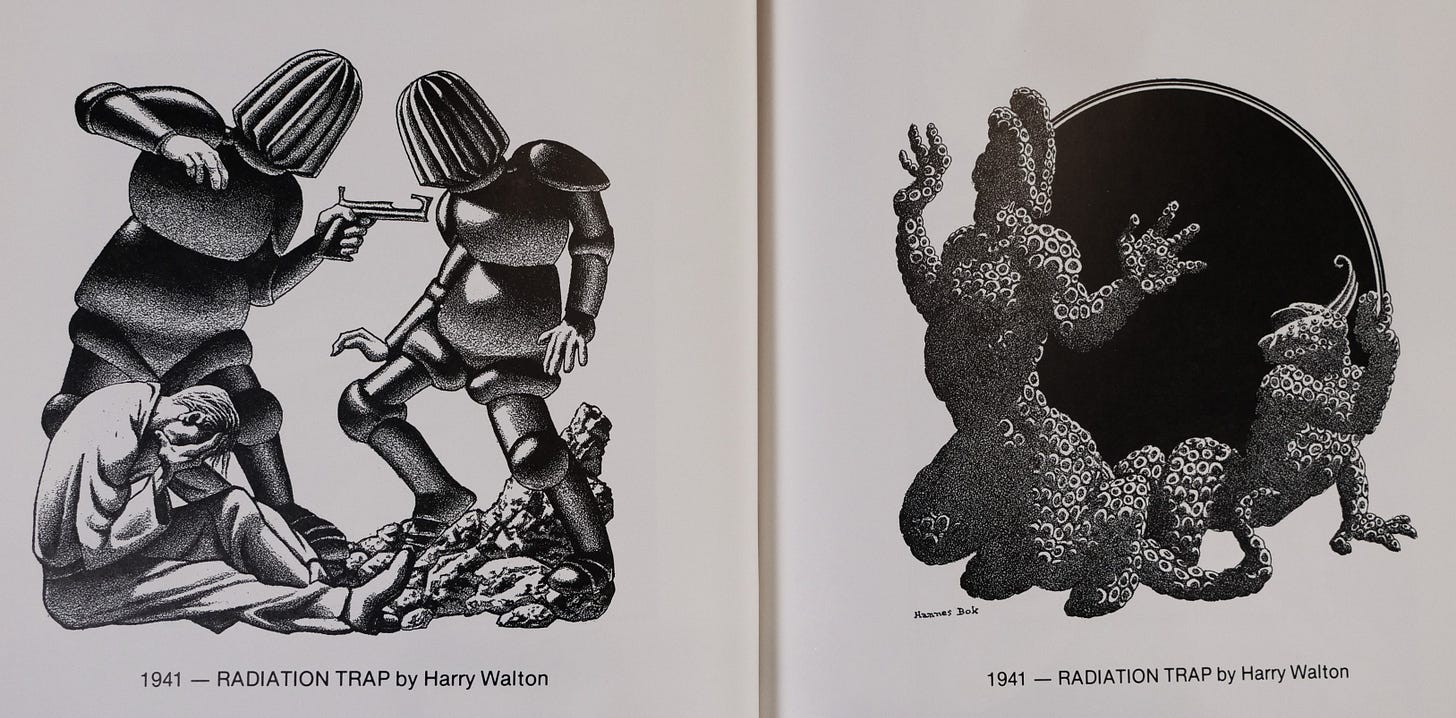

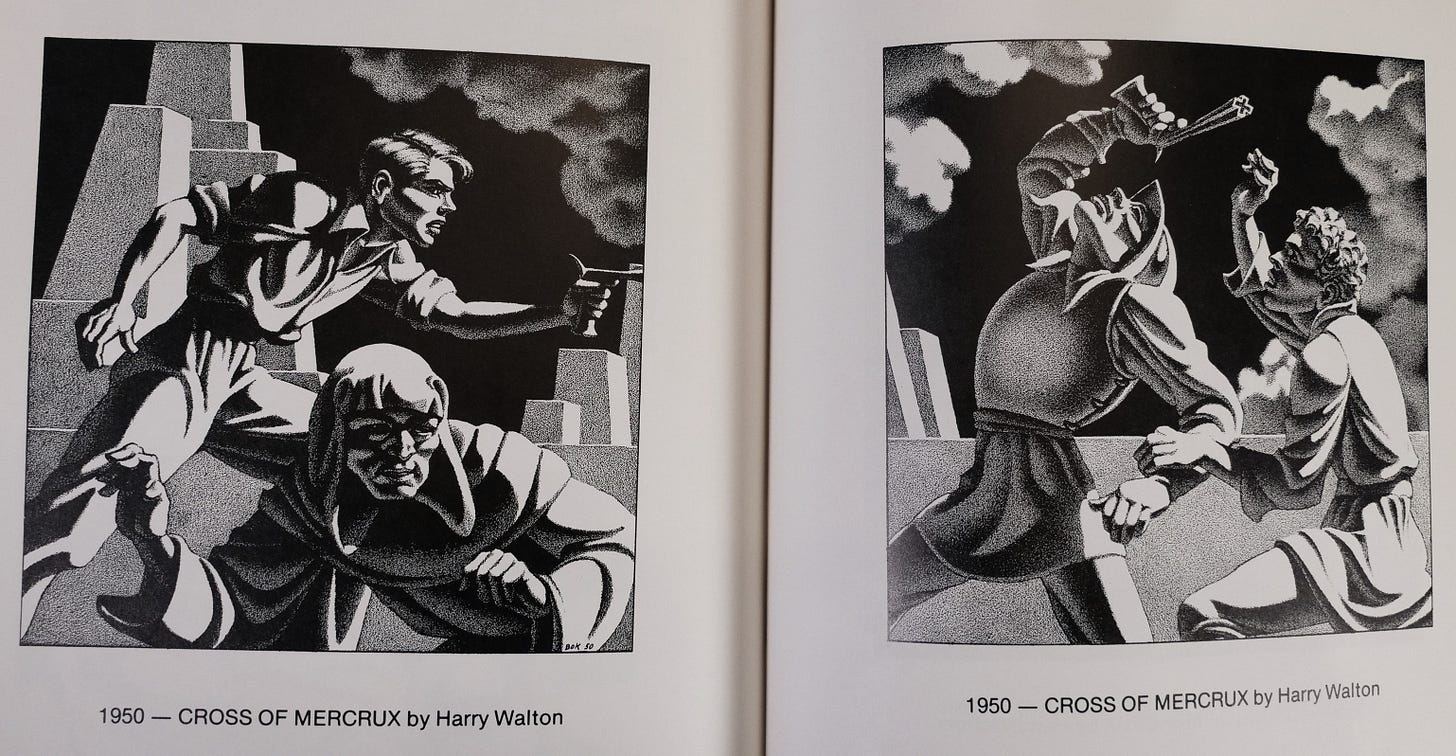

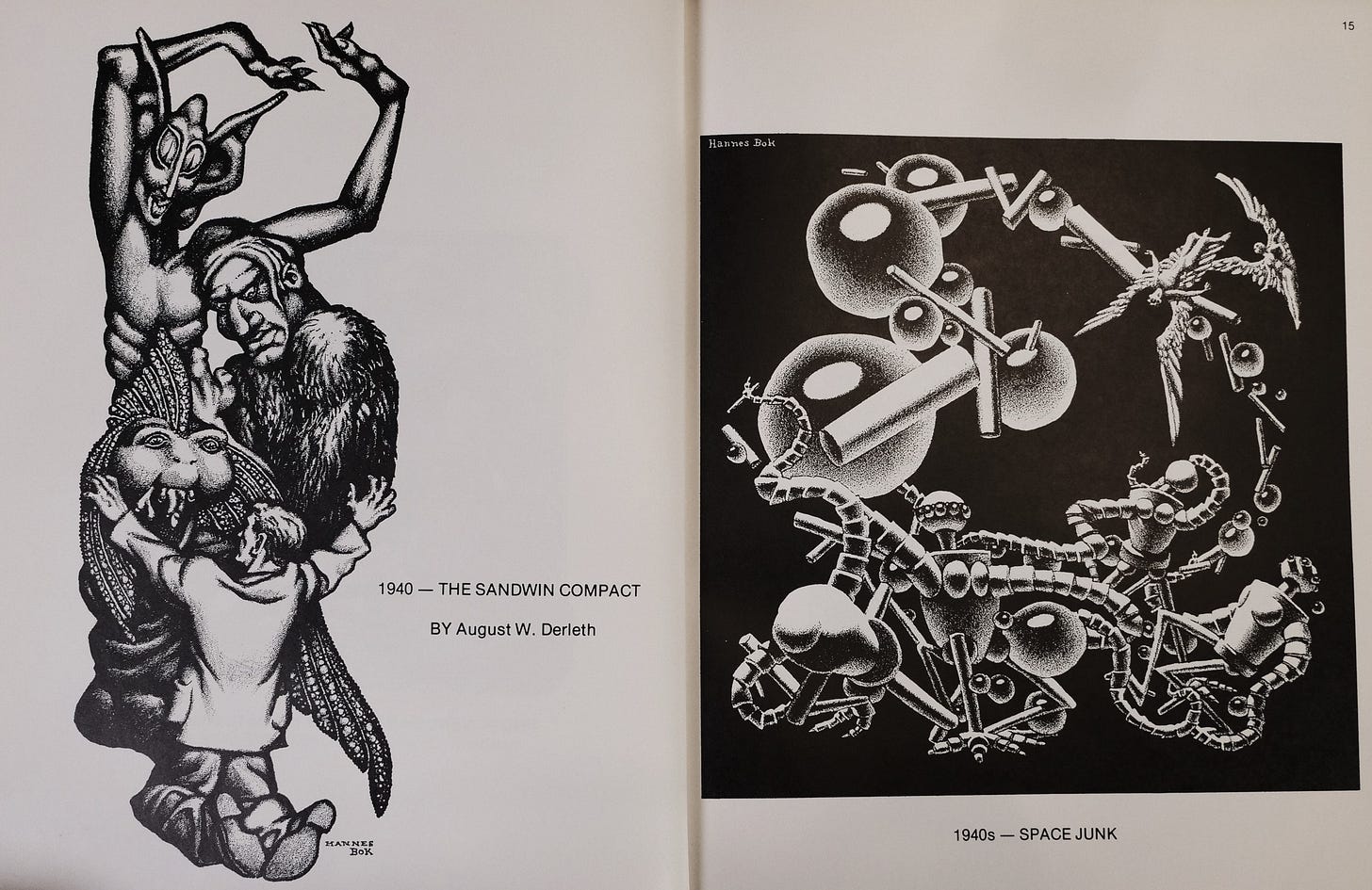

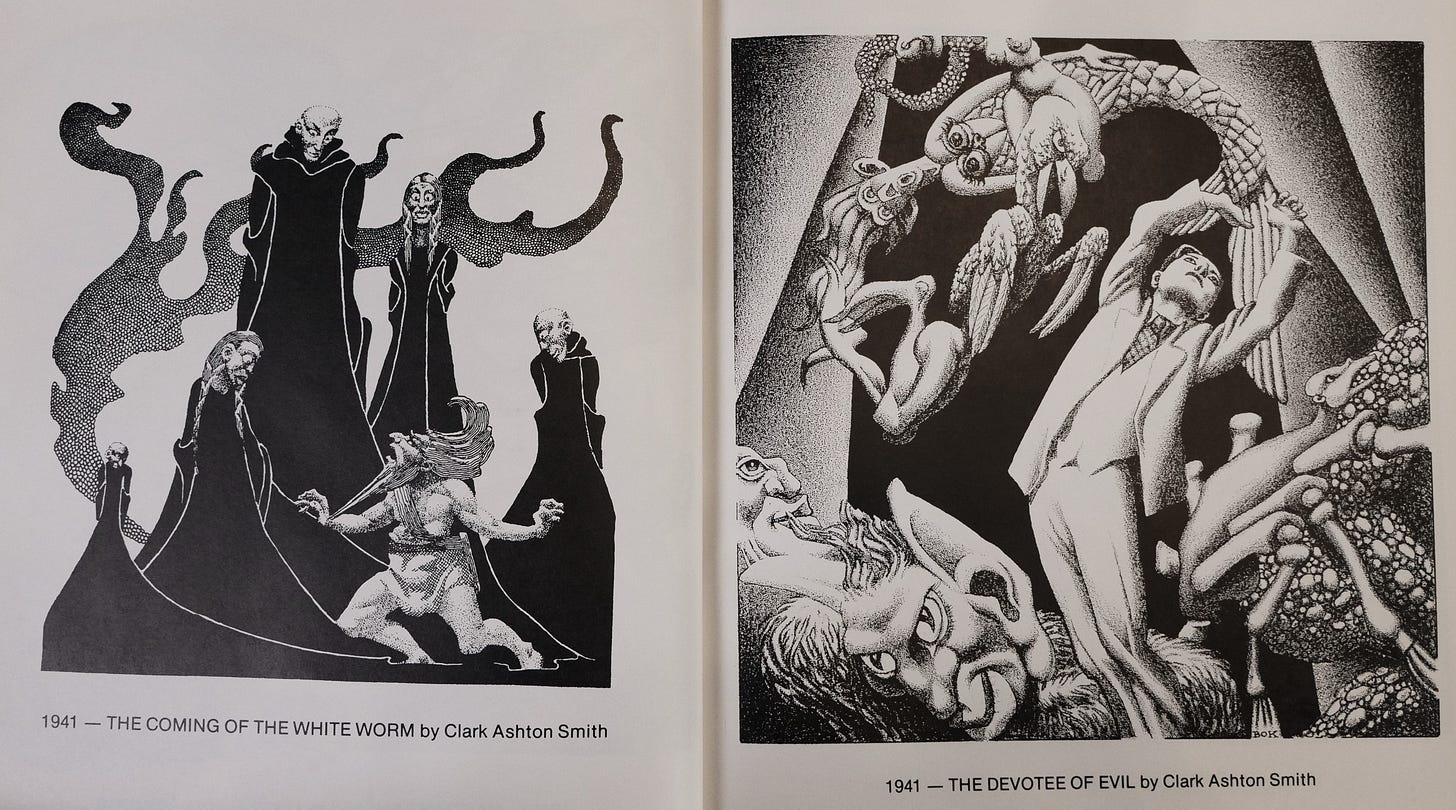

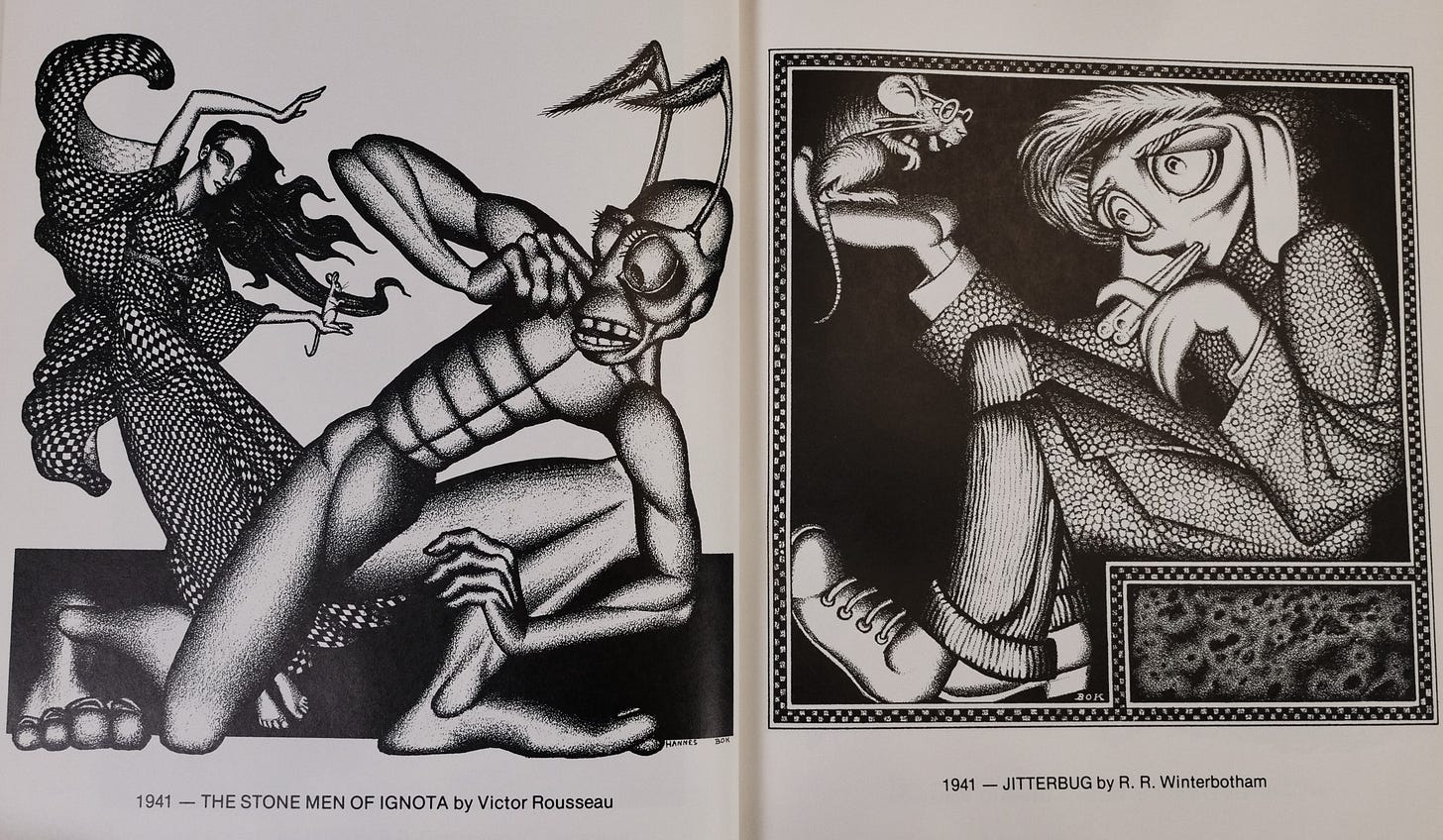

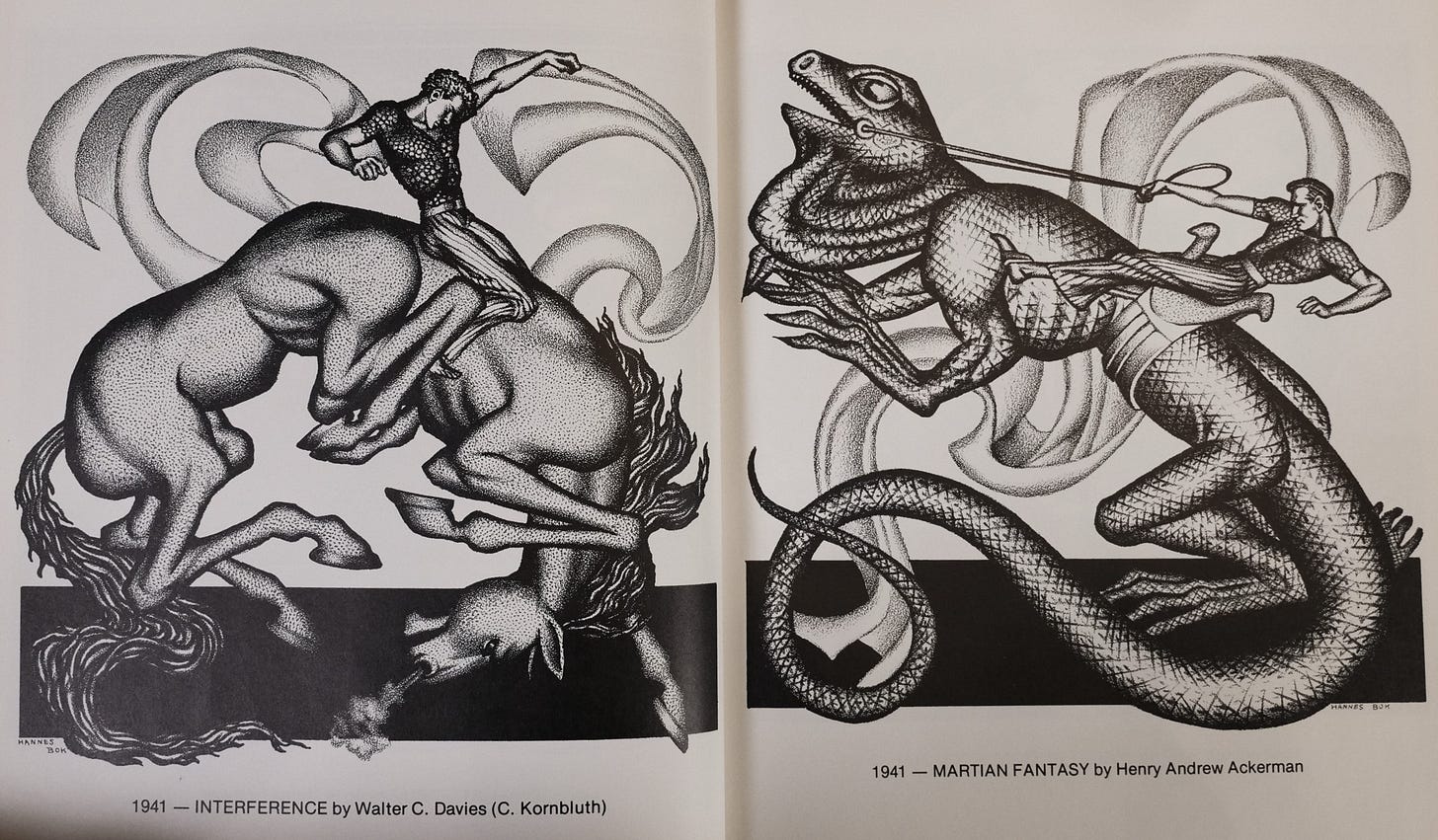

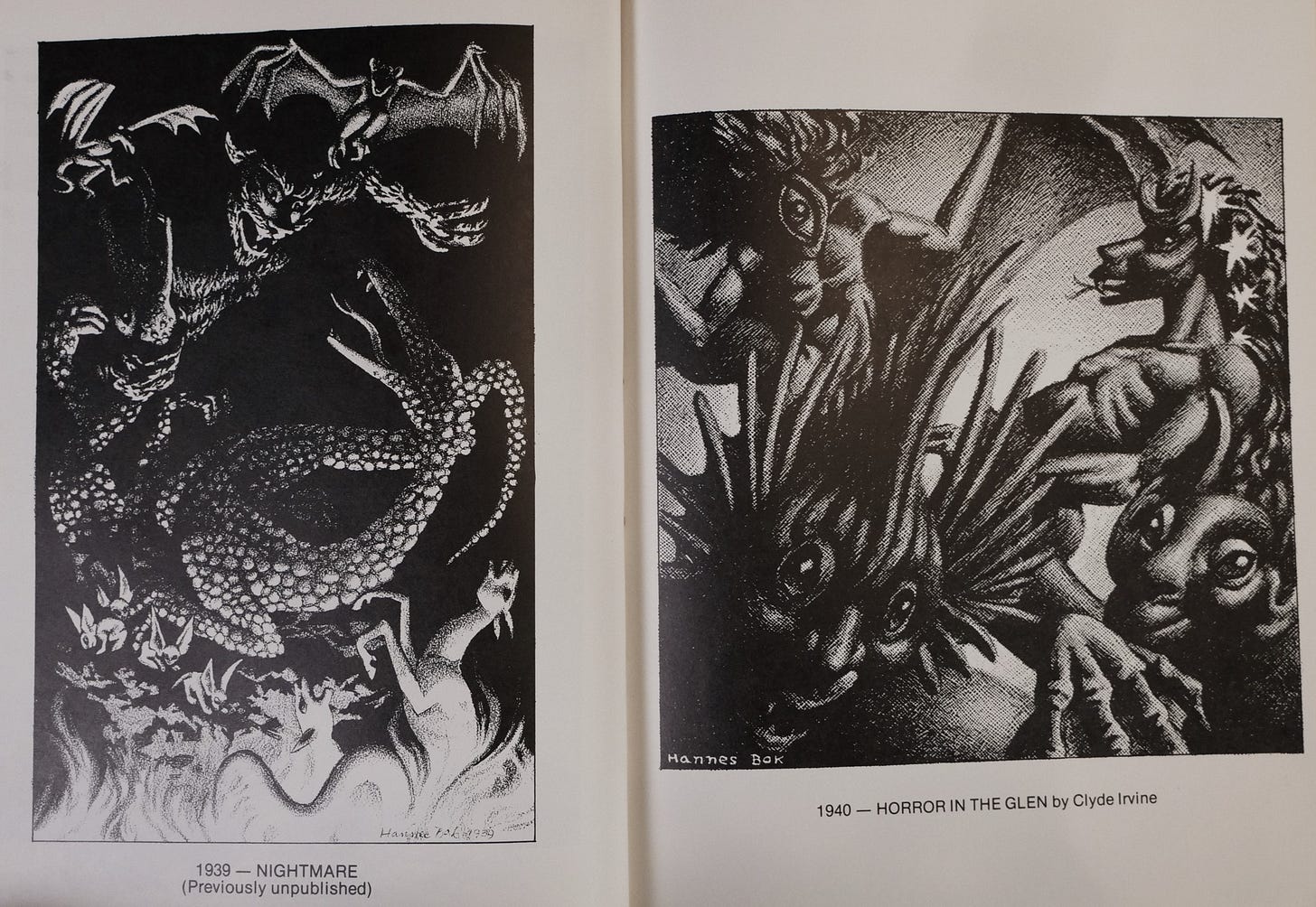

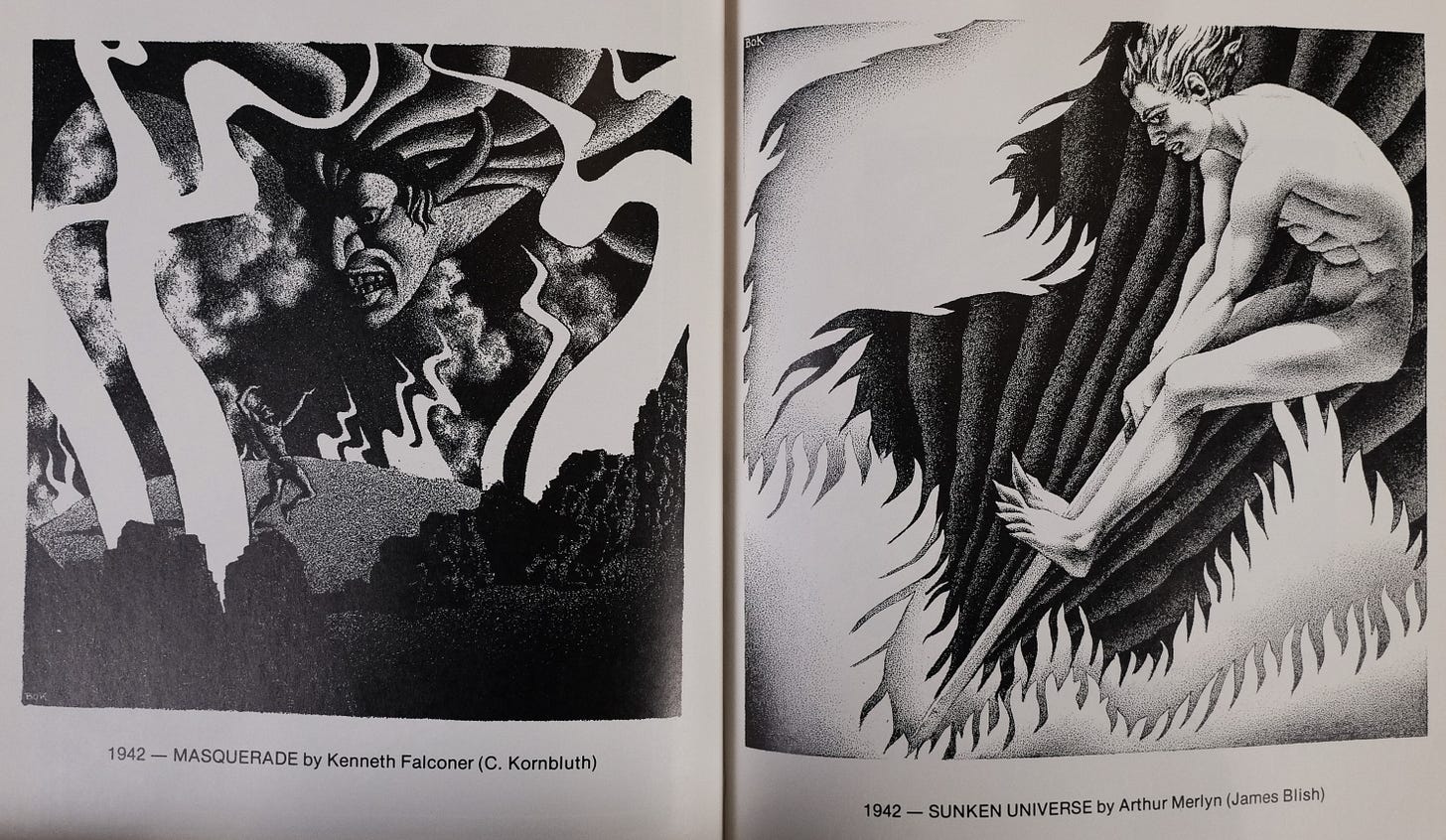

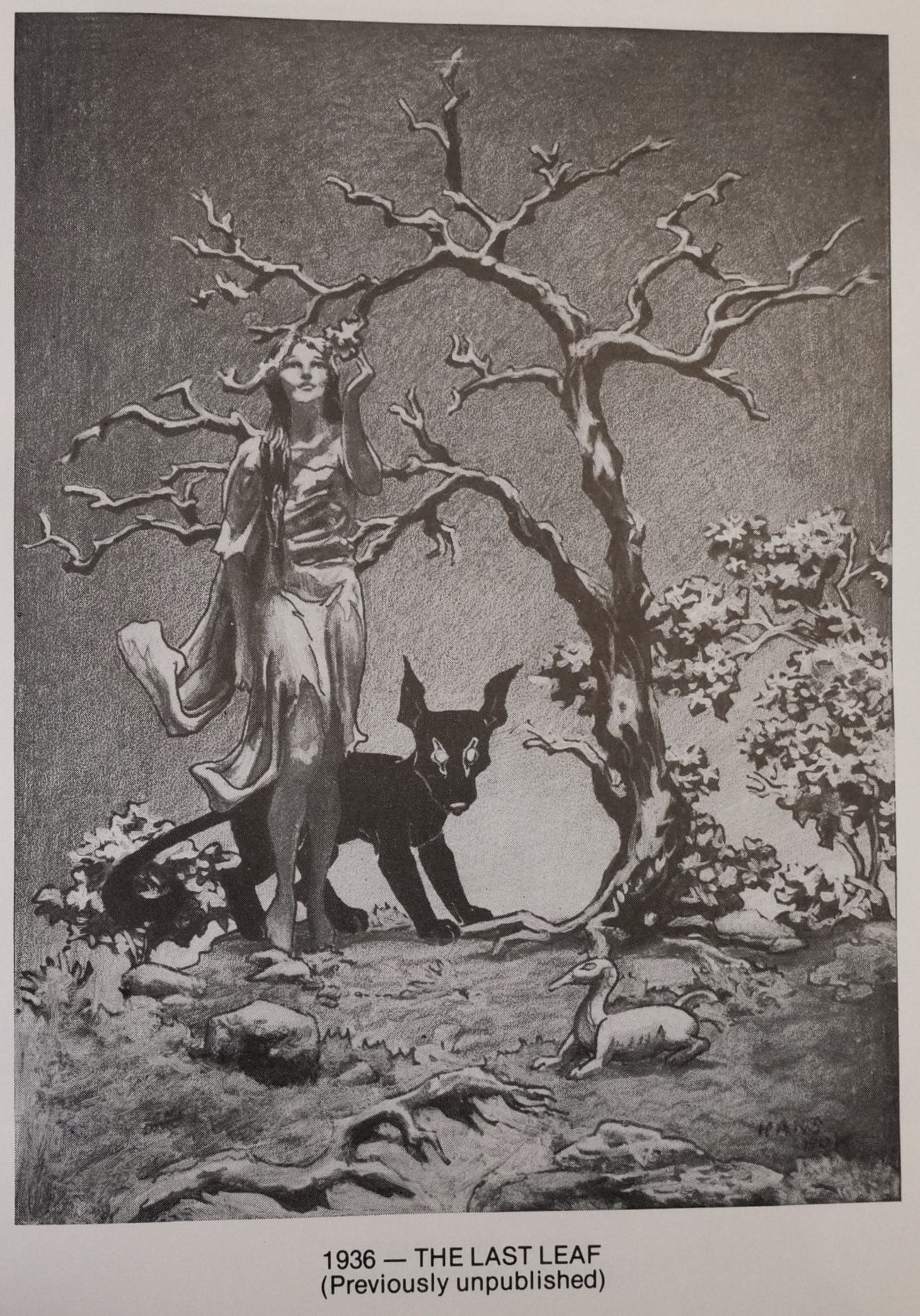

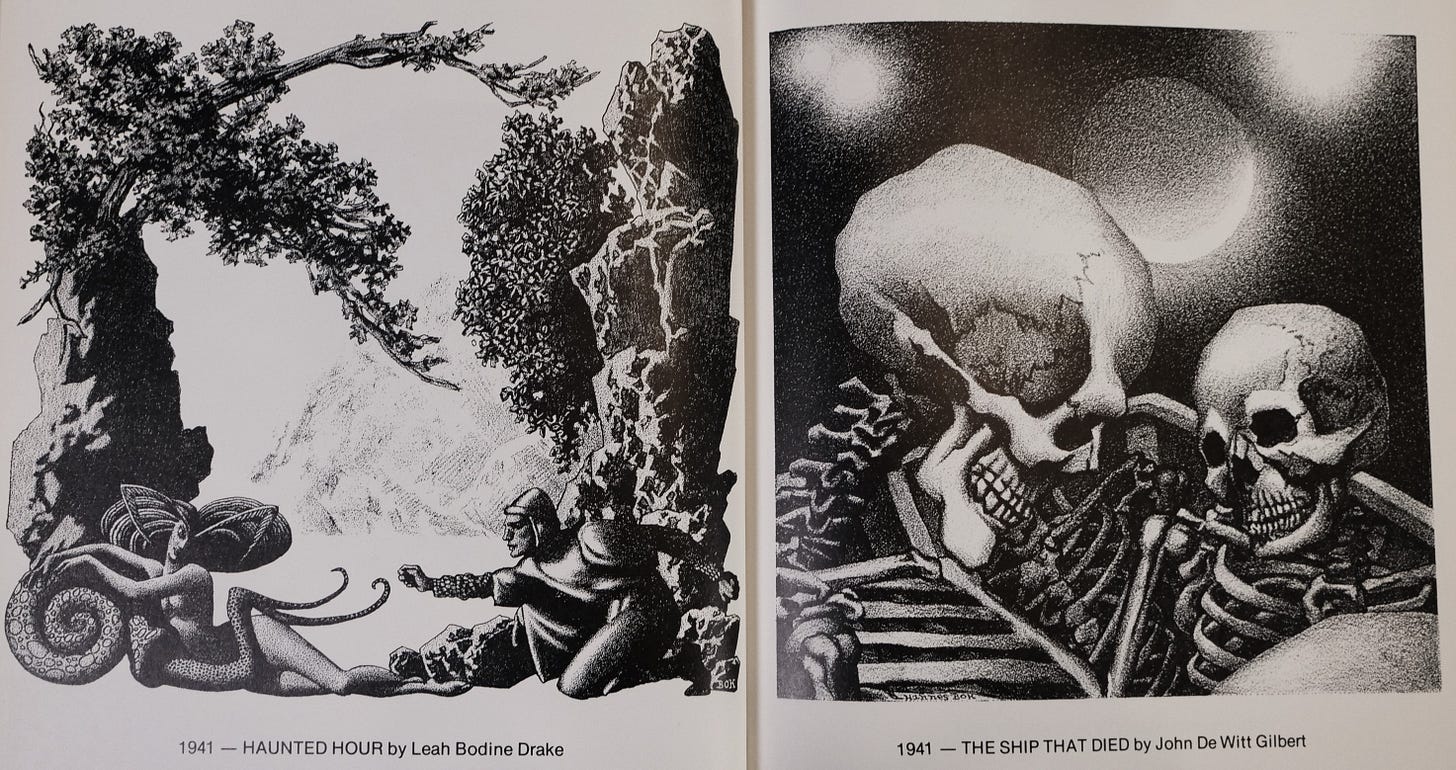

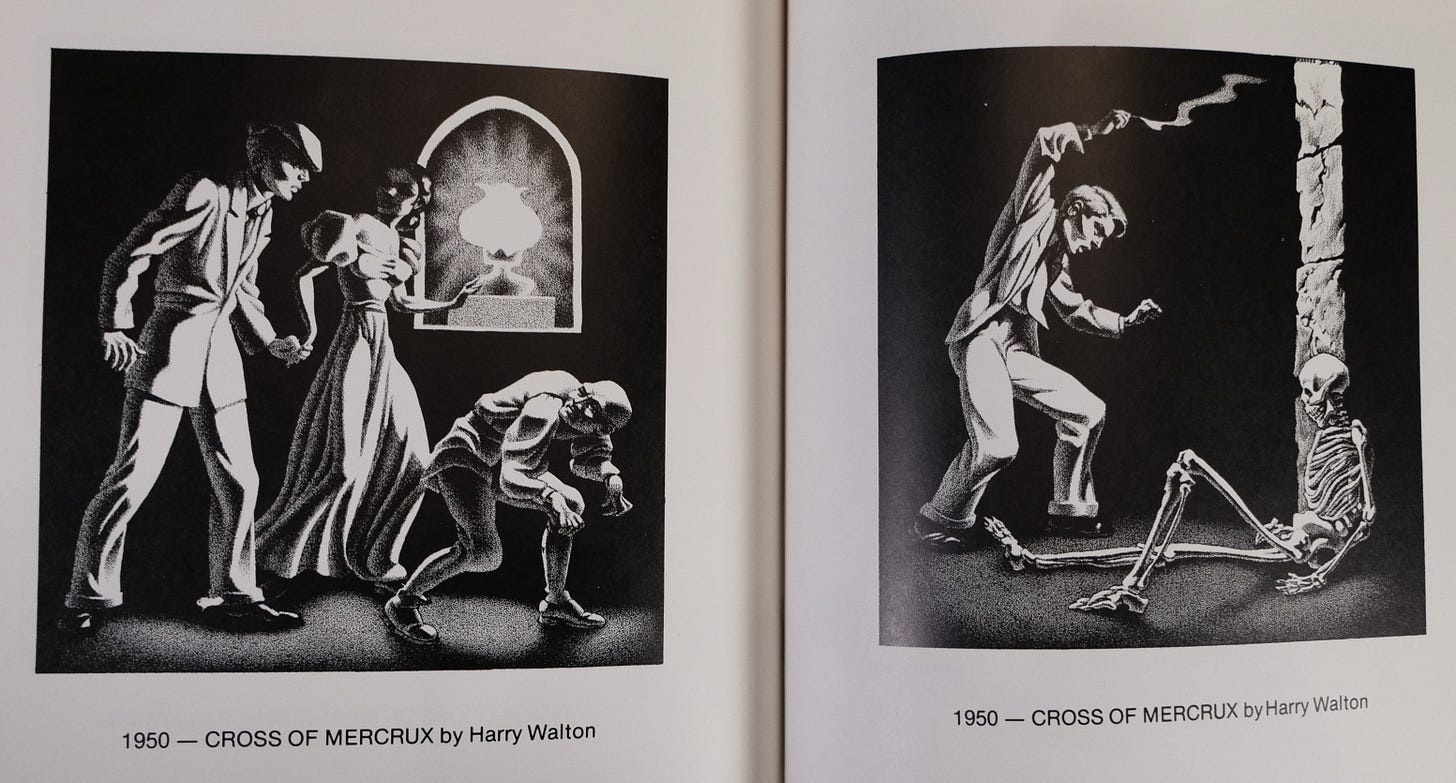

Bok’s surreal images and distinctive style were instantly recognizable. No one created pictures that made the grotesque look so beautiful (or the beautiful look so grotesque).

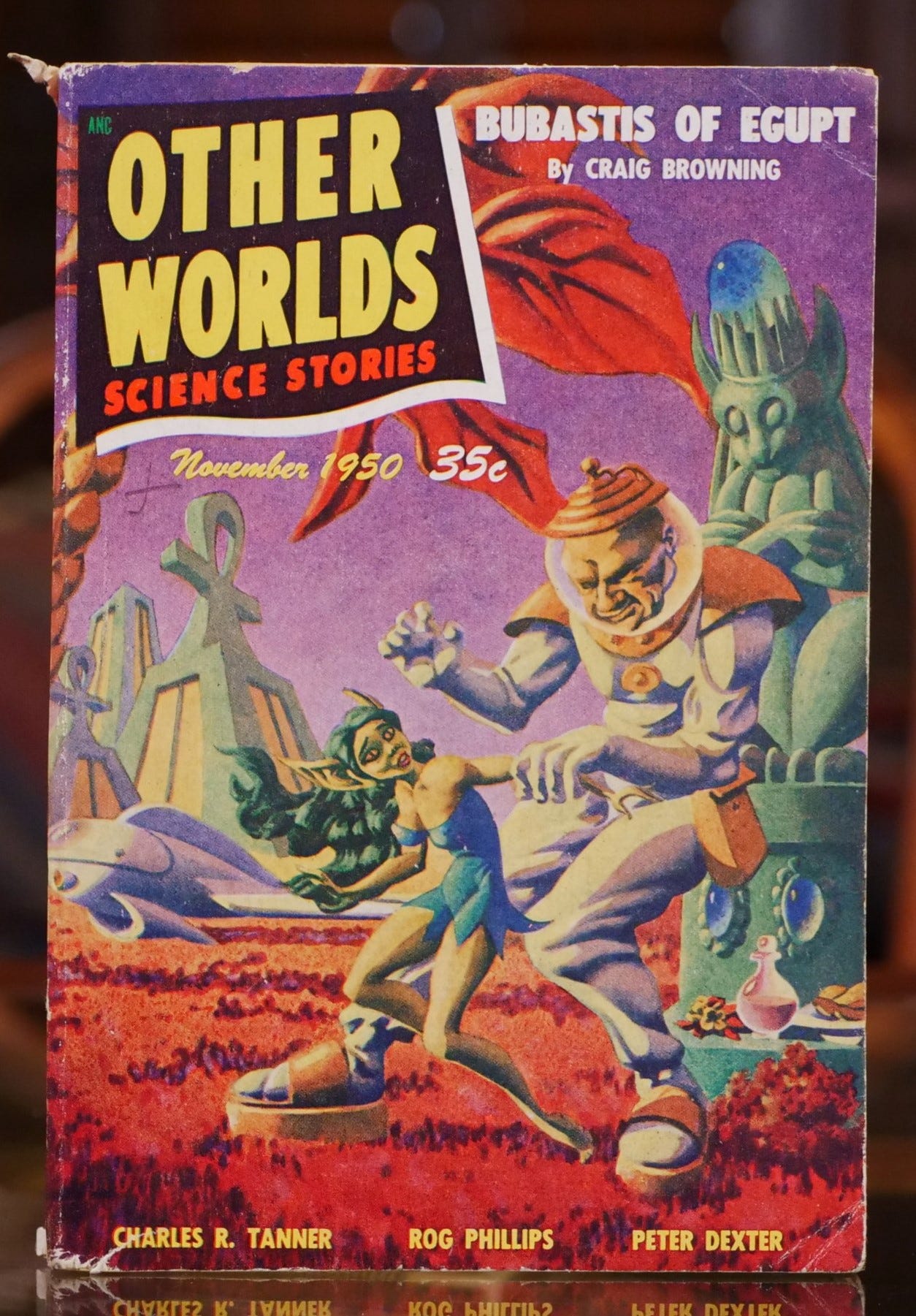

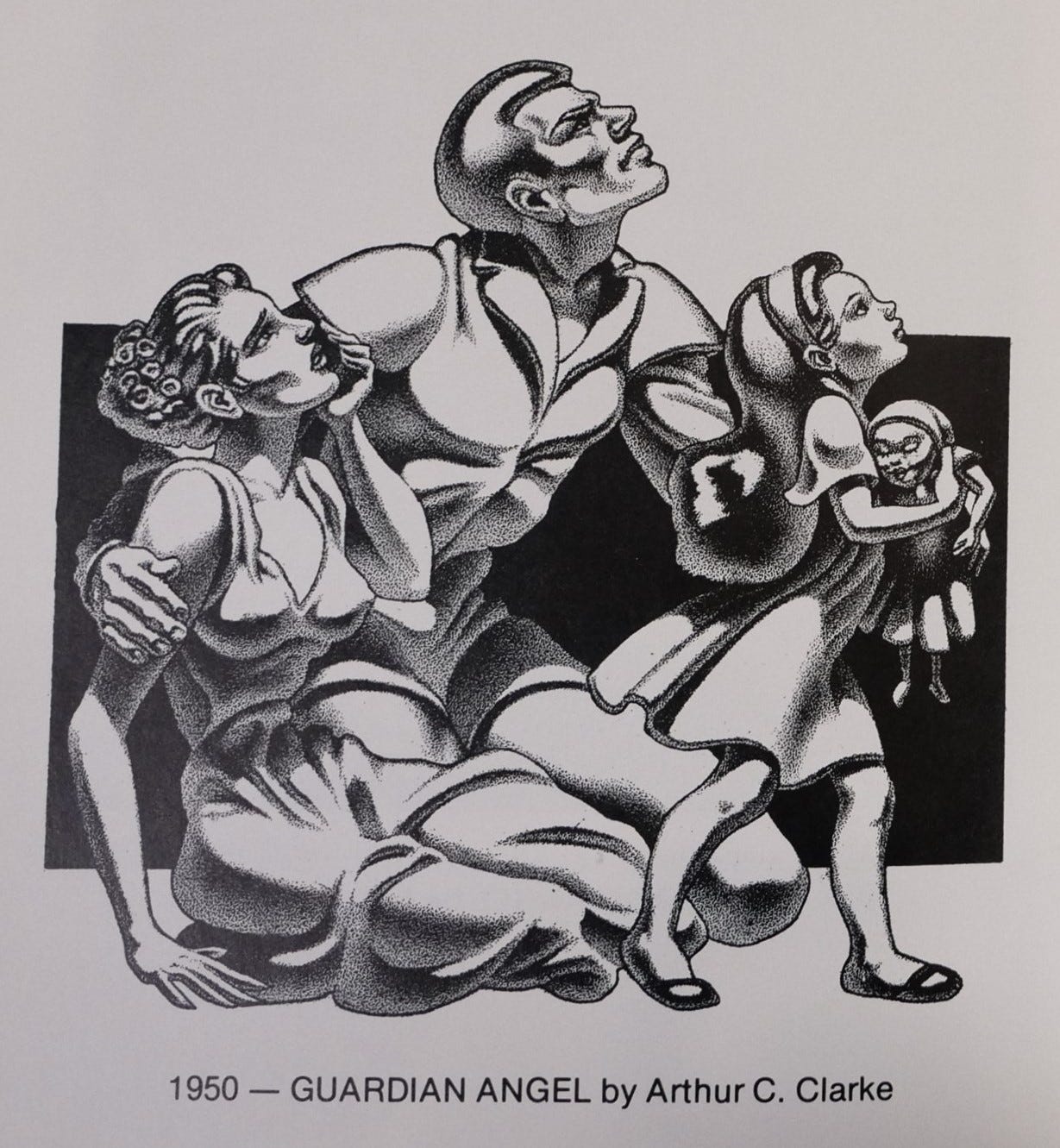

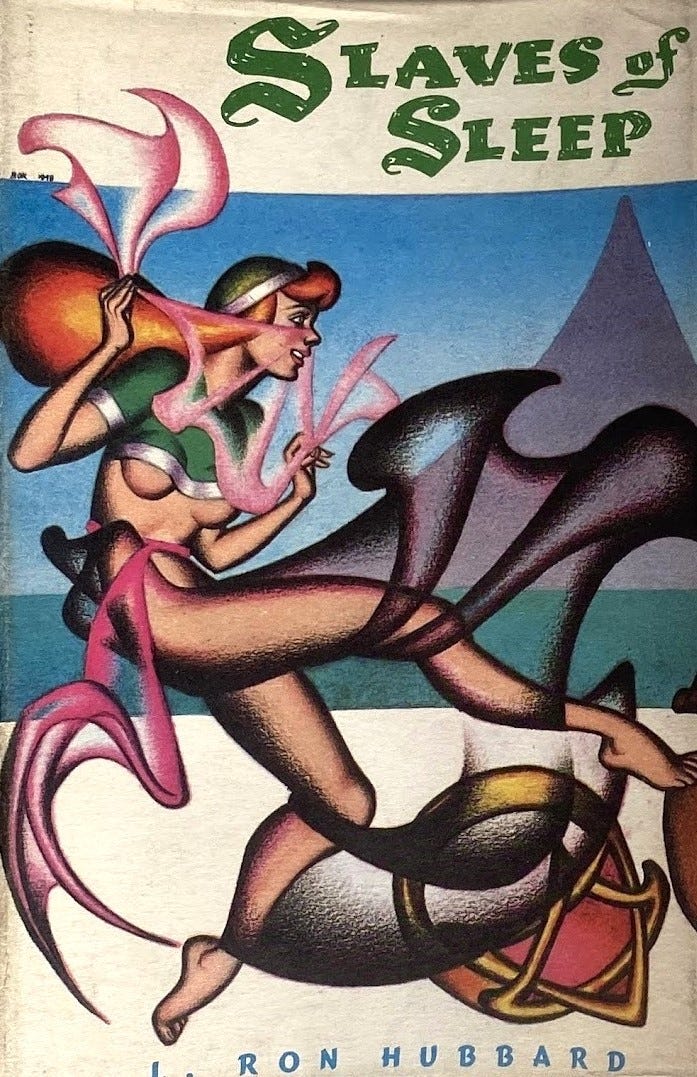

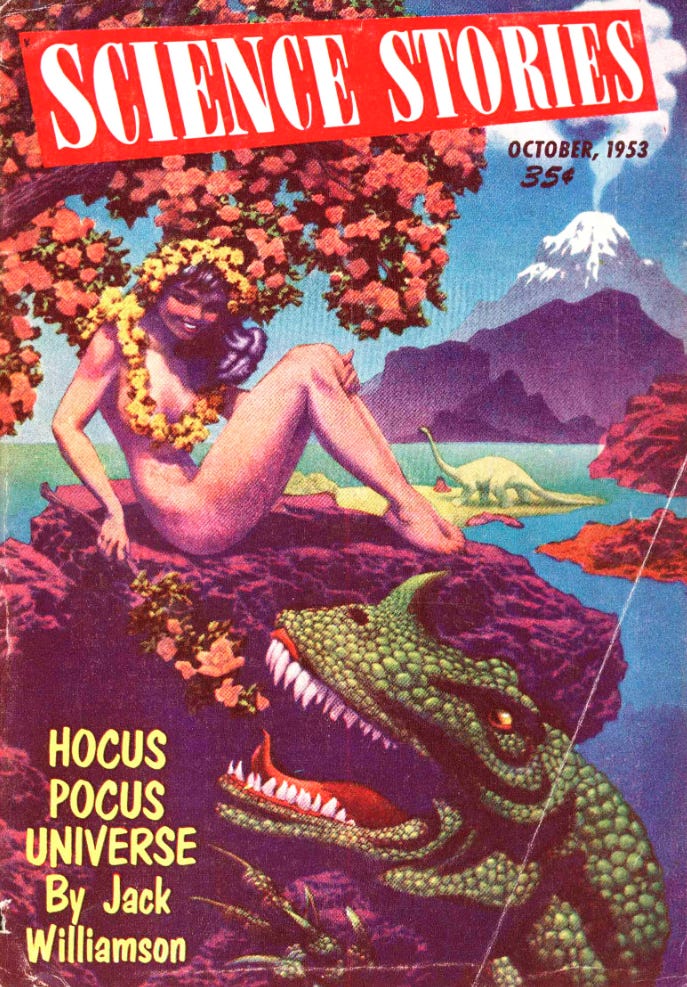

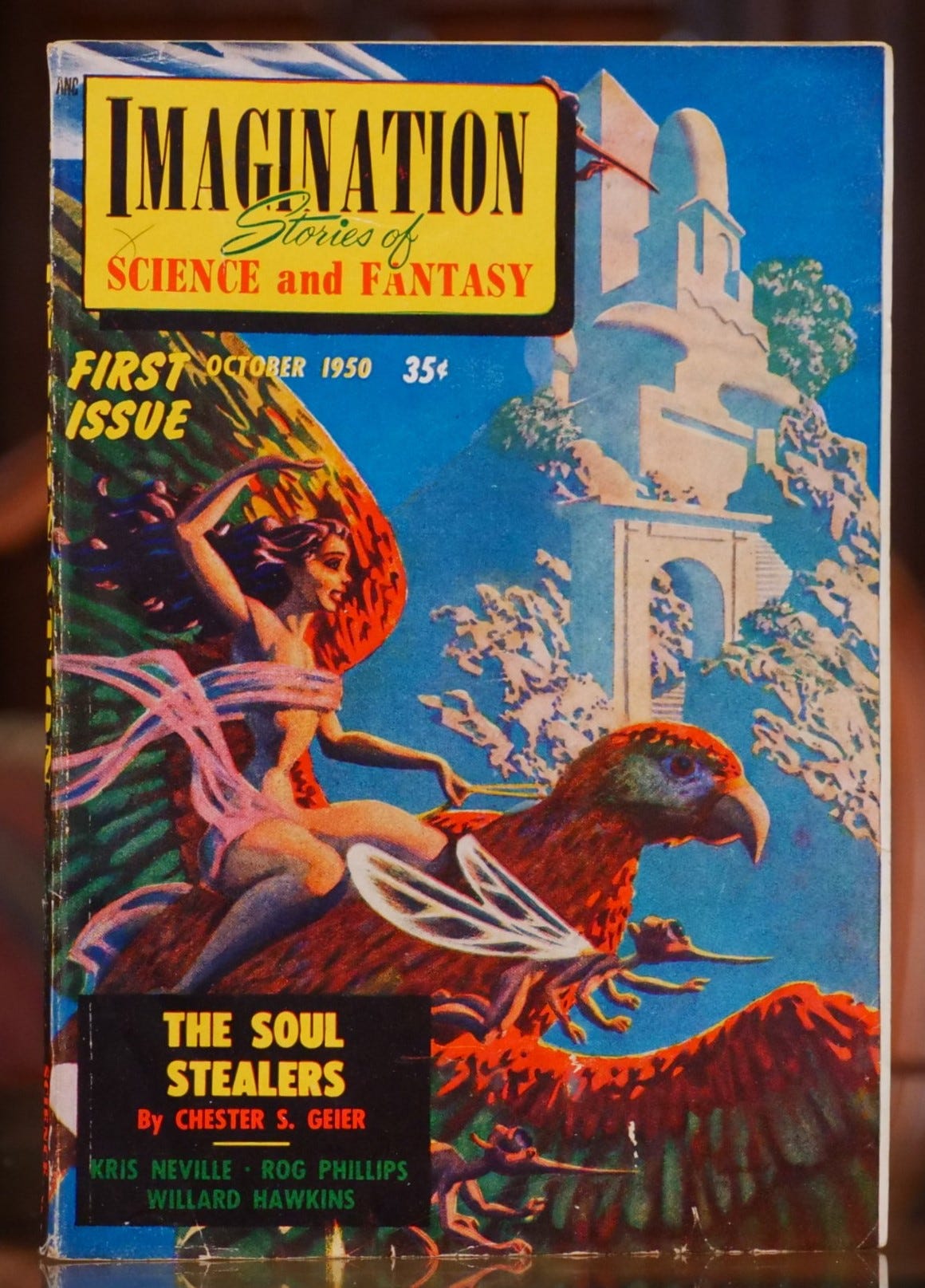

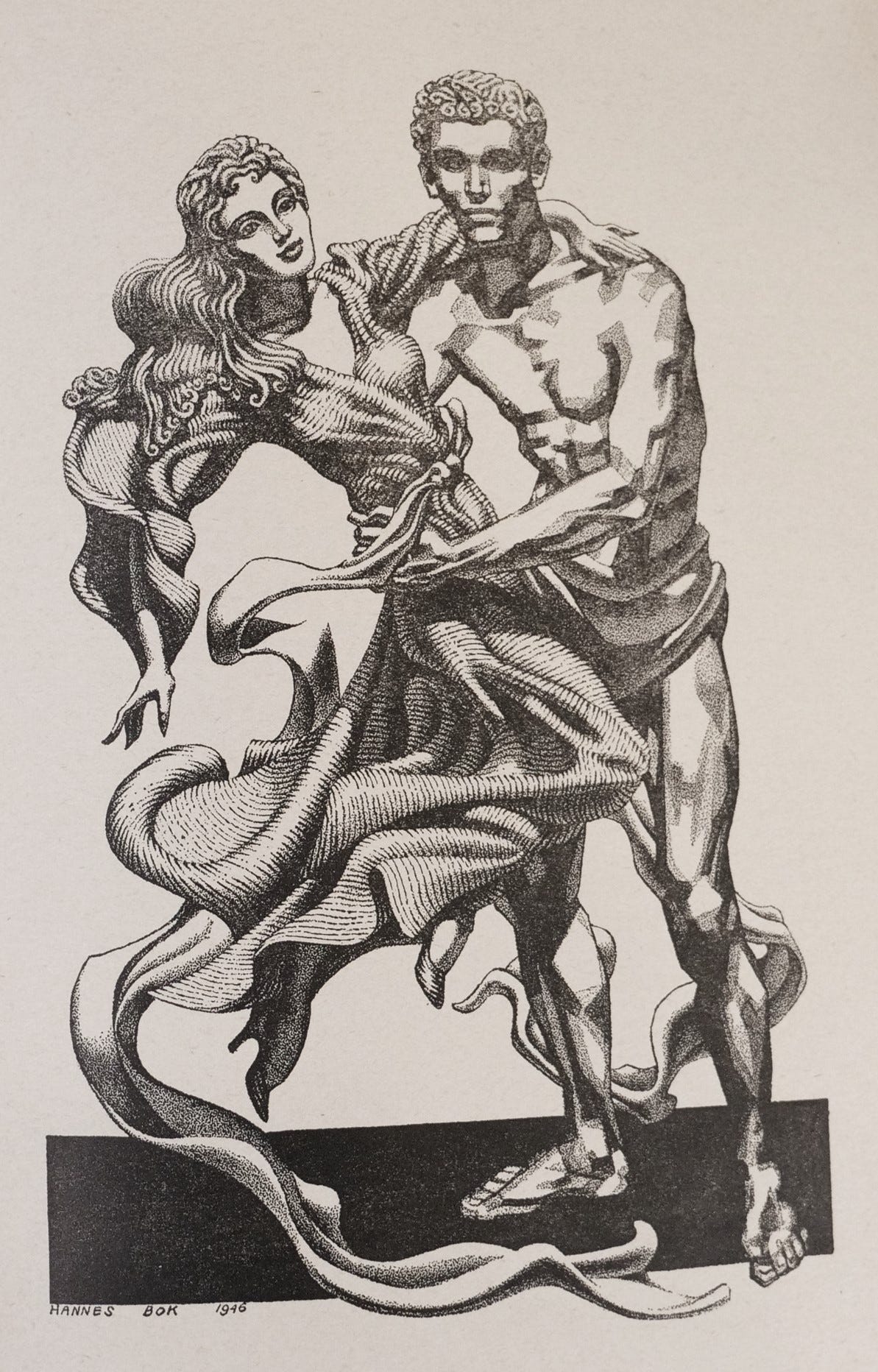

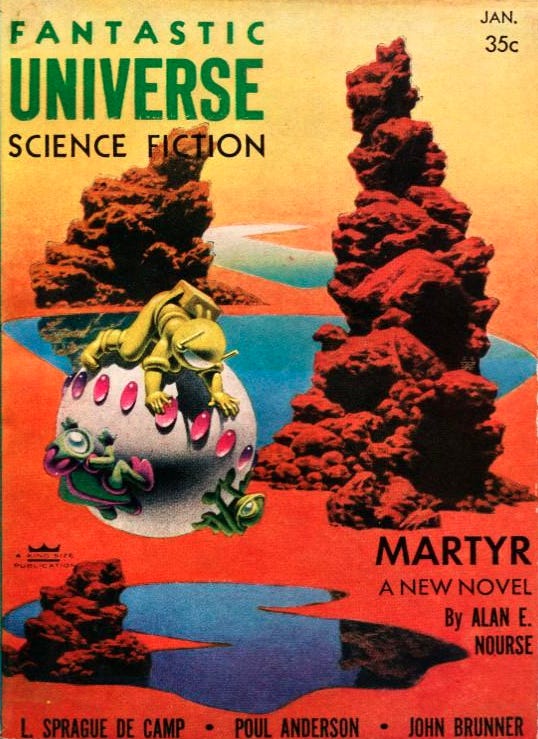

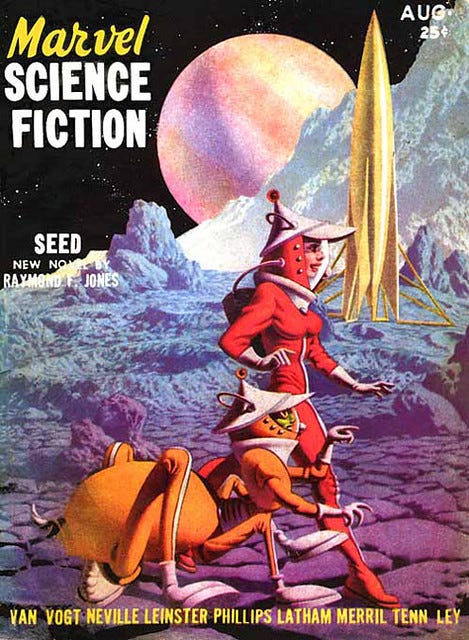

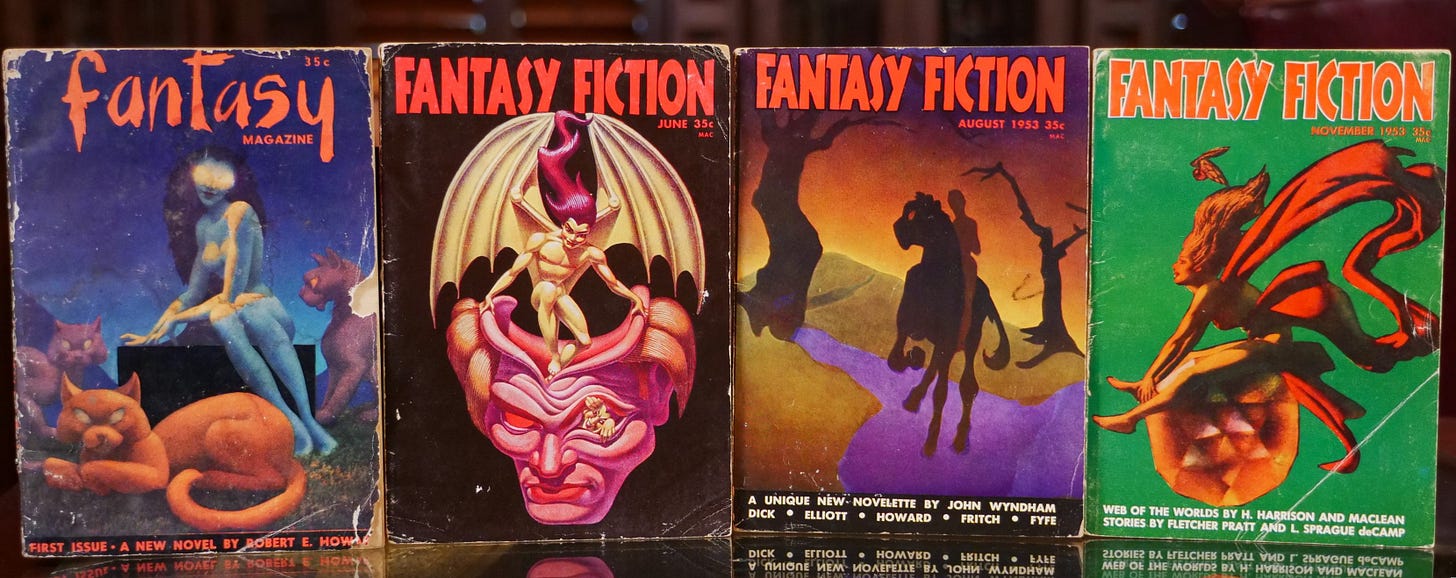

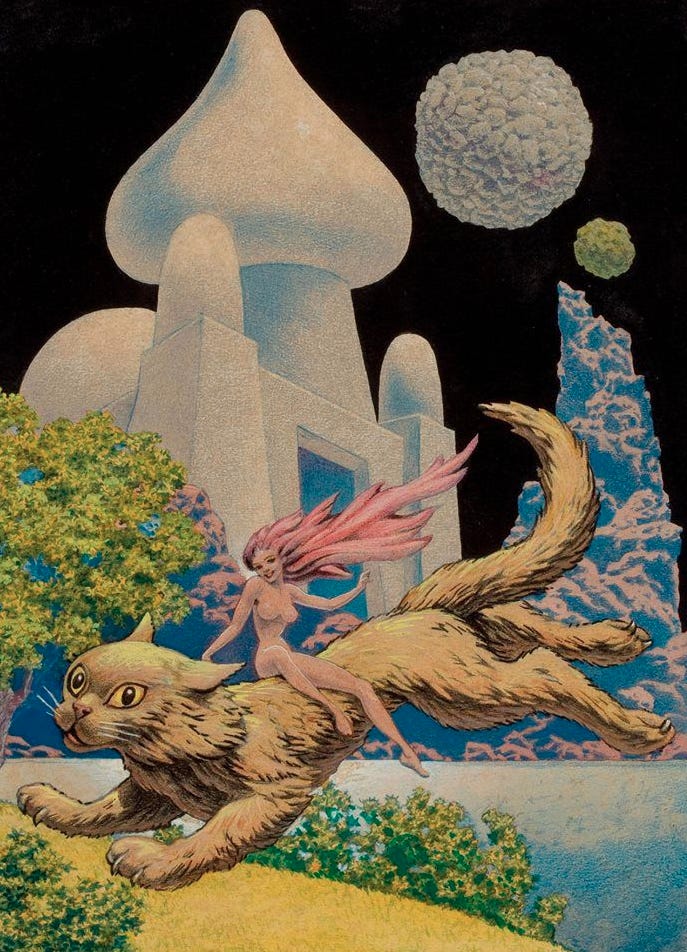

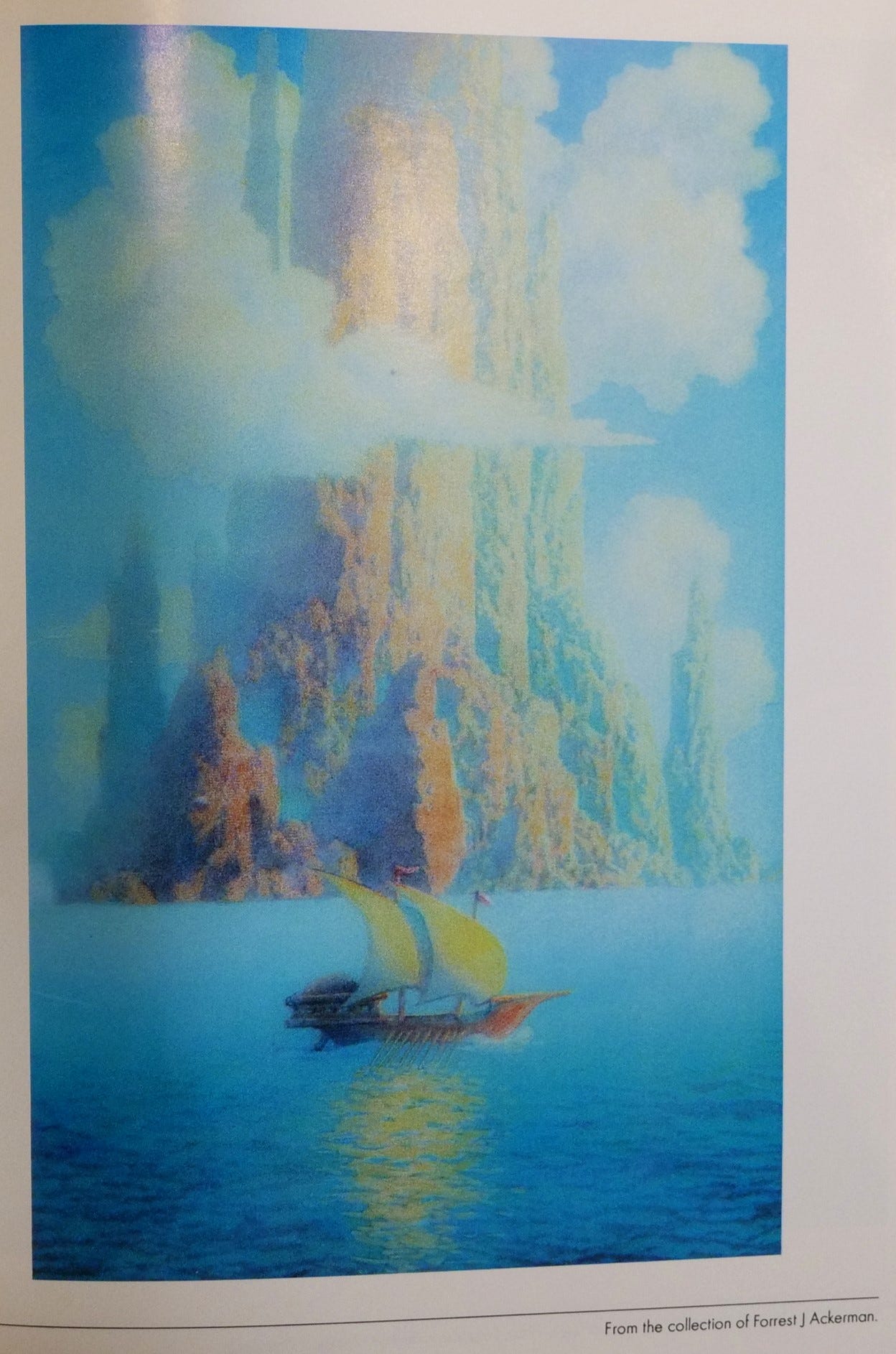

His cover art for books and magazines were famous for their vivid colors and bizarre, otherworldly imagery, while his black and white interior illustrations displayed his keen eye for shading and proportion.

There’s an uncanny suggestion of motion in his pictures, even when the people and other subjects are drawn in stationary poses. Some artists excel at depicting kinetic energy, but Bok filled his pages with potential energy, barely contained under the surface, that makes his subjects seem as if they’re just about to lunge forward, collapse, or start writhing in ecstasy or in pain.

A hallmark of his is the exaggerated proportions of his human subjects. Muscles never were so toned and pronounced. Breasts never looked so spherical and symmetrical. Enlarged facial features never looked so tortured with doubt or suffused with ennui.

Ironically, this wasn’t so much a stylistic choice for Bok as it was a practical one. Many of his early works were interior illustrations for pulp magazines that used coarse, uncoated paper unsuited to displaying fine details accurately. To compensate, he decided to draw his subjects with bold proportions to improve his control over how they’d appear on the page. As he became known for that style, he continued to use it even when illustrating glossy book and magazine covers.

There’s also a sexual suggestiveness that runs through many of his works – sometimes in the poses struck; sometimes in the Freudian symbols included; and sometimes in the tendency of his subjects to cavort in the nude (or close to it). It was quite daring for that time period.

Finally, the layering techniques he learned from his idol and mentor Maxfield Parrish give many of his paintings an ethereal and almost three-dimensional quality that no other speculative fiction artist at the time could match.

Two paintings by Bok and one by Parrish

Brief Biography

He was born Wayne Woodard in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1914. He moved to Duluth, Minnesota, during his childhood, where he caught speculative fiction fever in 1927 upon his first encounter with Abraham Merritt’s novel The Moon Pool serialized in Amazing Stories magazine. The illustrations by Frank R. Paul accompanying Merritt’s story inspired young Wayne’s decision to become an artist.

He had little formal art training other than an art class he took for two years in high school. At eighteen, he moved to Seattle during the worst period of the Great Depression. Unable to find work, he spent much of his time in museums, libraries and bookstores seeking ideas and insights as an aspiring artist trying to teach himself the fundamentals. In particular, he revered the artwork of Maxfield Parrish, with whom he corresponded and occasionally visited in the late 1930s, to learn Parrish’s distinctive techniques.

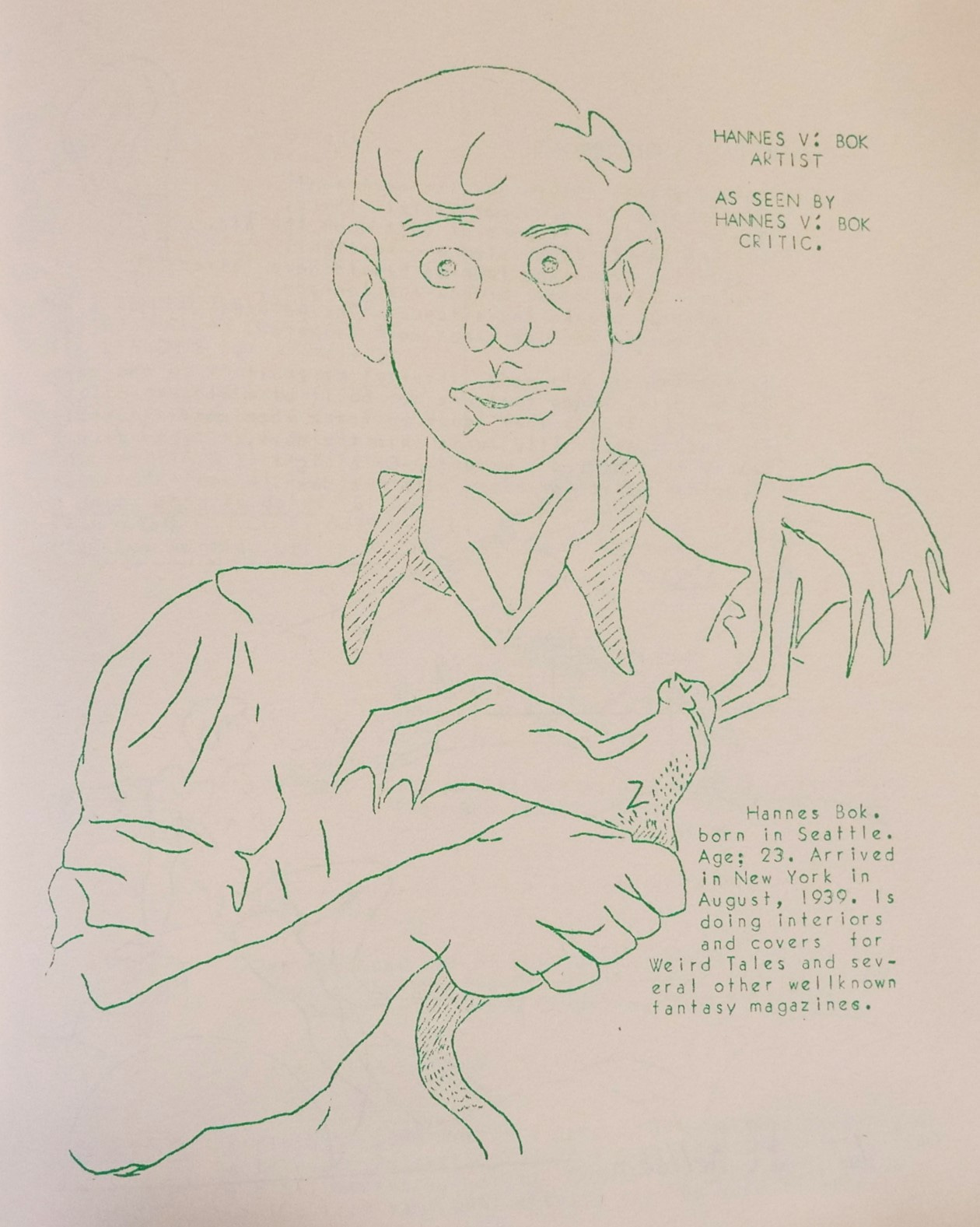

While in Seattle, he became close friends with budding speculative fiction author Emil Petaja. He also adopted the pseudonym Hans Bok, which he later changed to Hannes Bok. According to another close friend, SF author and editor Robert Lowndes, Bok chose the name because of his love for the music of German composer Johann S. Bach.

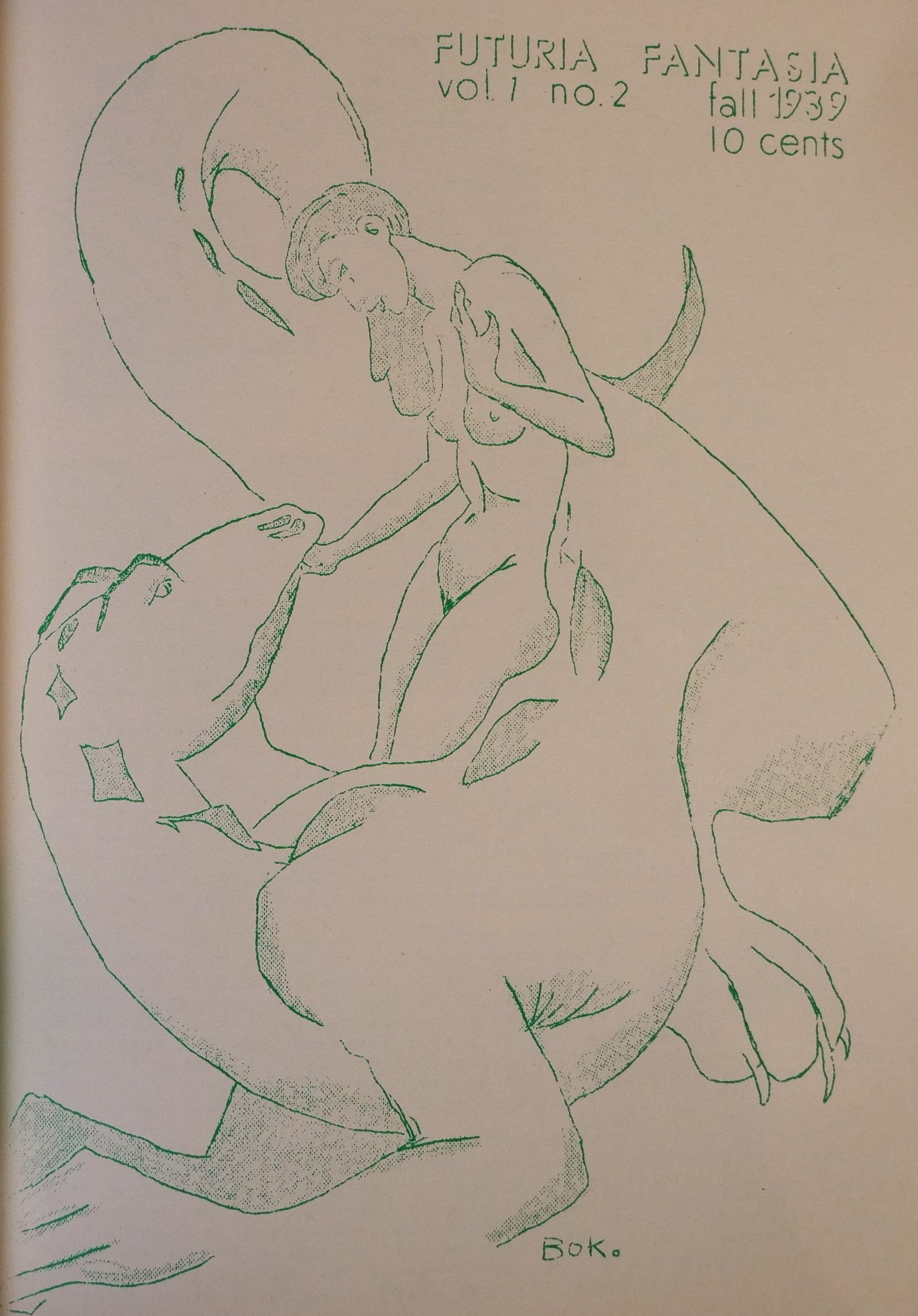

Petaja moved to Los Angeles in 1937 to join the burgeoning SF scene there, and he convinced Bok to accompany him. There, Bok befriended 18-year-old Ray Bradbury, who was planning an SF fan magazine called Futuria Fantasia containing original works of short fiction, poetry and commentary of his own and that of SF fans and authors such as Robert Heinlein, Henry Kuttner, Forrest Ackerman, Damon Knight, and Petaja. Bradbury loved Bok’s artwork and asked him to contribute to the fanzine.

Bok responded by giving Bradbury a collection of sketches and paintings he considered his ‘discards,’ and Bradbury used them in all four issues of Futuria Fantasia. The fanzine even published a few of Bok’s written works as well.

In return, Bradbury offered to bring a portfolio of Bok’s artwork to New York for the first World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon) in the summer of 1939. While there, Bradbury met with several pulp magazine editors on Bok’s behalf to interest them in Bok’s works, and Farnsworth Wright, editor of Weird Tales, offered Bok a job providing illustrations for the magazine.

Bok immediately moved to New York and lived there the rest of his life.

Once in New York, Bok produced seven cover paintings and 49 interior illustrations for Weird Tales between December 1939 and March 1942, quickly becoming one of the magazine’s primary artists. His work for Weird Tales slackened after 1944, but his art continued to appear in it for the next decade.

Bok also associated himself with the Futurians, an influential group of science fiction fans and authors in the New York area who embraced utopian goals and visions for SF, often tinged with communist sympathies. Club members included current and future luminaries such as Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, Damon Knight, James Blish, Cyril Kornbluth, Judith Merril, Robert Lowndes and Donald Wollheim.

Pohl, Lowndes and Wollheim worked as editors of several SF pulp magazines in the 1940s, and Bok’s friendship with them enabled him to get work producing dozens of illustrations for Super Science Stories, Science Fiction, Fantasy Fiction, Cosmic Stories and Stirring Science Stories, among others.

He needed the work, as the life of a pulp magazine illustrator was far from lucrative. In the early 1940s, he received only $50 for a magazine cover illustration, while interior drawings earned considerably less.

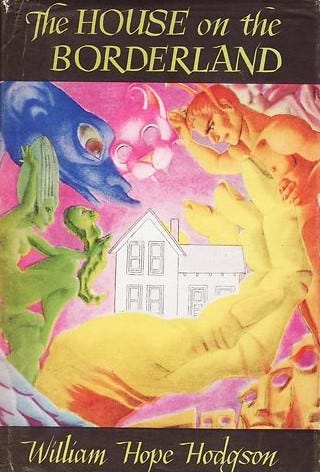

The emergence of small specialty presses such as Arkham House, Gnome Press, Fantasy Press and Shasta Publishers in the 1940s created new opportunities for Bok. He designed the covers of four of the most sought-after Arkham House titles—Clark Ashton Smith’s Out of Space and Time in 1942; and Frank Belknap Long’s The Hounds of Tindalos, William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland, and Robert E. Howard’s Skull-Face and Others, all in 1946. The Skull-Face cover is my favorite piece by Bok.

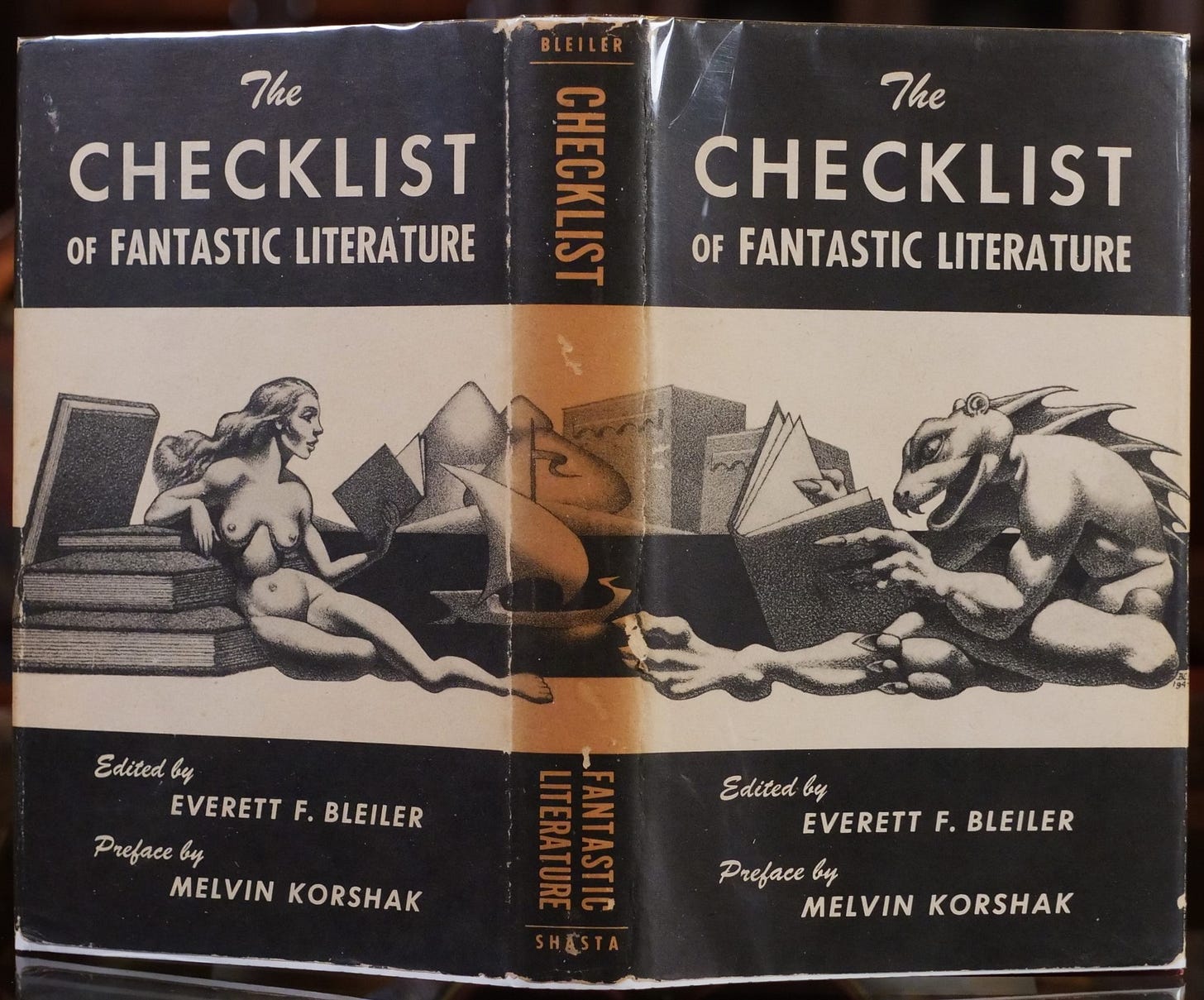

Bok provided artwork for the cover of Shasta Publishers’ first book, Everett F. Bleiler’s Checklist of Fantastic Literature in 1948, a sketch of which was also used as Shasta’s corporate logo.

Other Shasta covers he produced include:

Who Goes There?, by John W. Campbell (1948); Slaves of Sleep, by L. Ron Hubbard (1948); The Wheels of If, by L. Sprague de Camp (1948); Sidewise in Time, by Murray Leinster (1950); and Kinsmen of the Dragon, by Stanley Mullen (1951).

For Fantasy Press, he produced seven cover illustrations, including those for:

Seven Out of Time, by Arthur Leo Zagat (1949); Beyond Infinity, by Robert Spencer Carr (1951); The Moon Is Hell, by John W. Campbell (1951); The Crystal Horde, by John Taine (1952); The Titan, by P. Schuyler Miller (1952); Alien Minds, by E. Everett Evans (1955); and Under the Triple Suns, by Stanton Coblentz (1955).

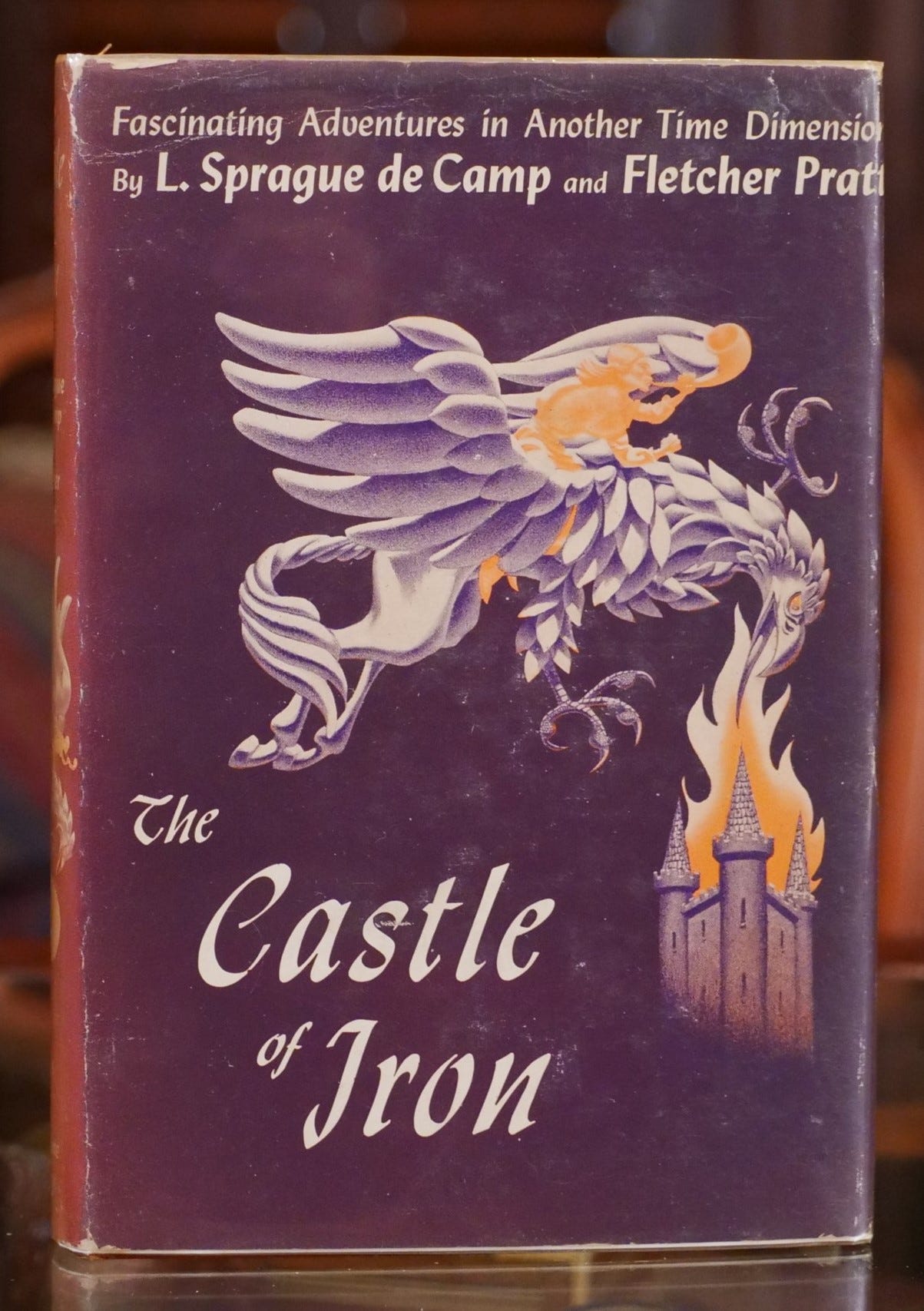

His work for Gnome Press included the cover of The Castle of Iron, by L. Sprague de Camp & Fletcher Pratt (1950), and several plates for the 1949 and 1950 Gnome Press calendars.

He also designed the cover art for The Green Man of Graypac, by Festus Bragnell; Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Camp (1949); and the cover and several interior plates for The Blind Spot, by Austin Hall & Homer Eon Flint (1951) from small publishers Greenberg and Prime Press.

Many of his book and magazine covers were actually only preliminary drafts of what were intended to be more polished works. His slow creative process led many publishers to insist on using unfinished works to meet their publication deadlines. Those unfinished works were still extraordinary, and it makes me wonder what they might have looked like when completed.

Bok was at the peak of his popularity in the early 1950s, and he won the very first Hugo Award for best cover artist in 1953, sharing the award with Ed Emshwiller.

However, that popularity took its toll on him. An outgoing person by nature (he was described as “elfin” by friends who knew him in the late 1930s), he became increasingly reclusive over the years. Toxic fans stalked him, invaded his home and workshop, and demanded free samples of his artwork, leading him to disengage from fan-led events and organizations and to live much like a hermit.

By the mid-1950s, he also was souring on his work for the speculative fiction industry. He considered himself an artist rather than an illustrator. He didn’t like creating art to fit someone else’s story. Instead, he preferred to create his pictures first and then let the publishers and authors craft stories to fit them. He enjoyed science fiction, but was frustrated by its increasing popularity, as it crowded out opportunities to create his preferred kinds of fantastical art that were more suitable for fantasy and weird fiction. And his unhappiness was compounded by bad experiences with unscrupulous publishers who failed to pay what they owed him.

In the final years of his life, he worked primarily as a writer publishing astrological commentary, although he still occasionally produced artwork for magazines. His final commercial illustration is one of his greatest—the November 1963 cover of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction depicting a scene from Roger Zelazny’s short story A Rose for Ecclesiastes.

He died a few months later at the age of 49.

Hannes Bok the Author

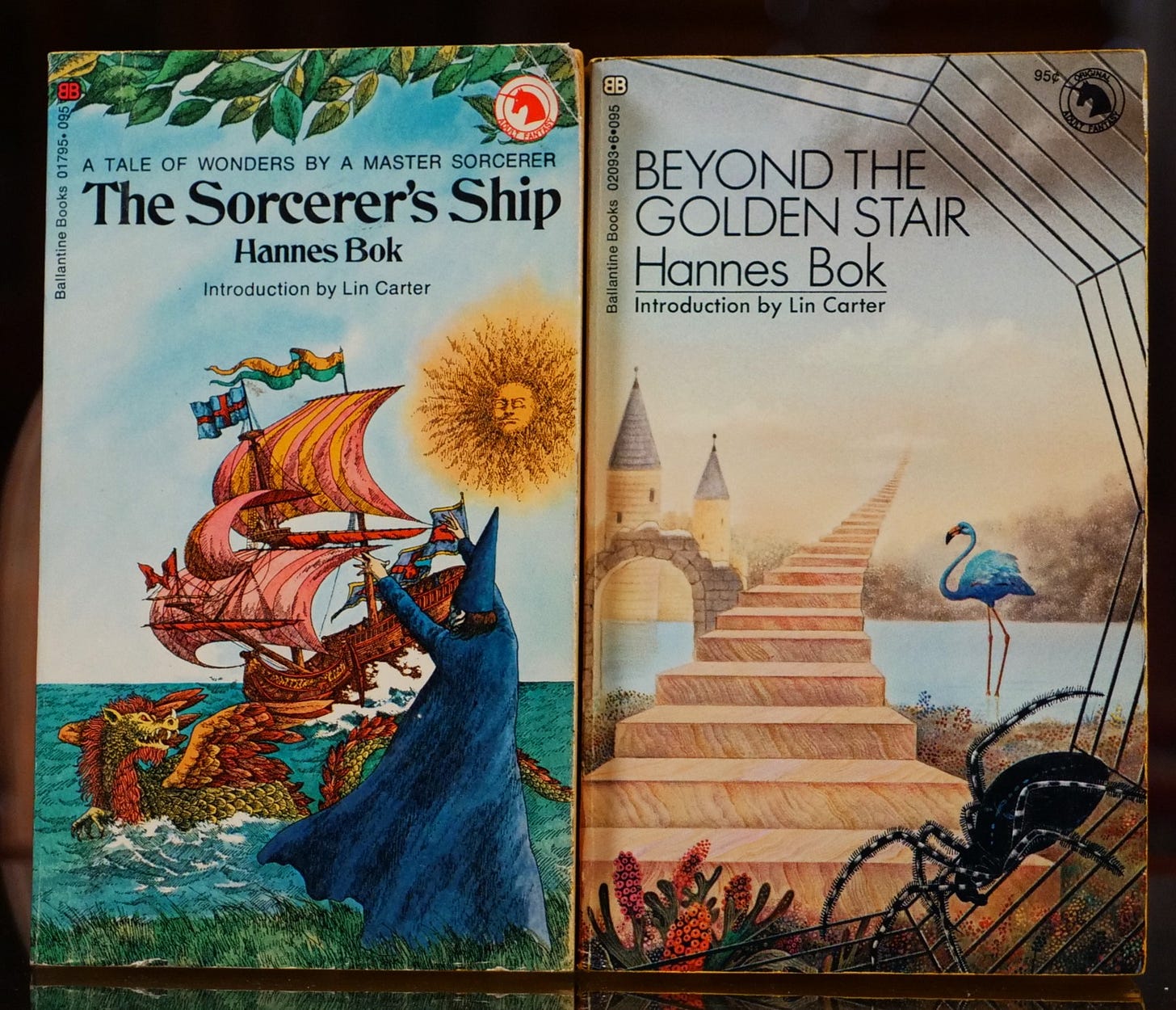

Bok wrote two novels, The Sorceror’s Ship and Beyond the Golden Stair, that were published in the pulp magazines Unknown and Startling Stories in the 1940s. Both were published in book form decades later as part of Ballantine Books’ Adult Fantasy Series.

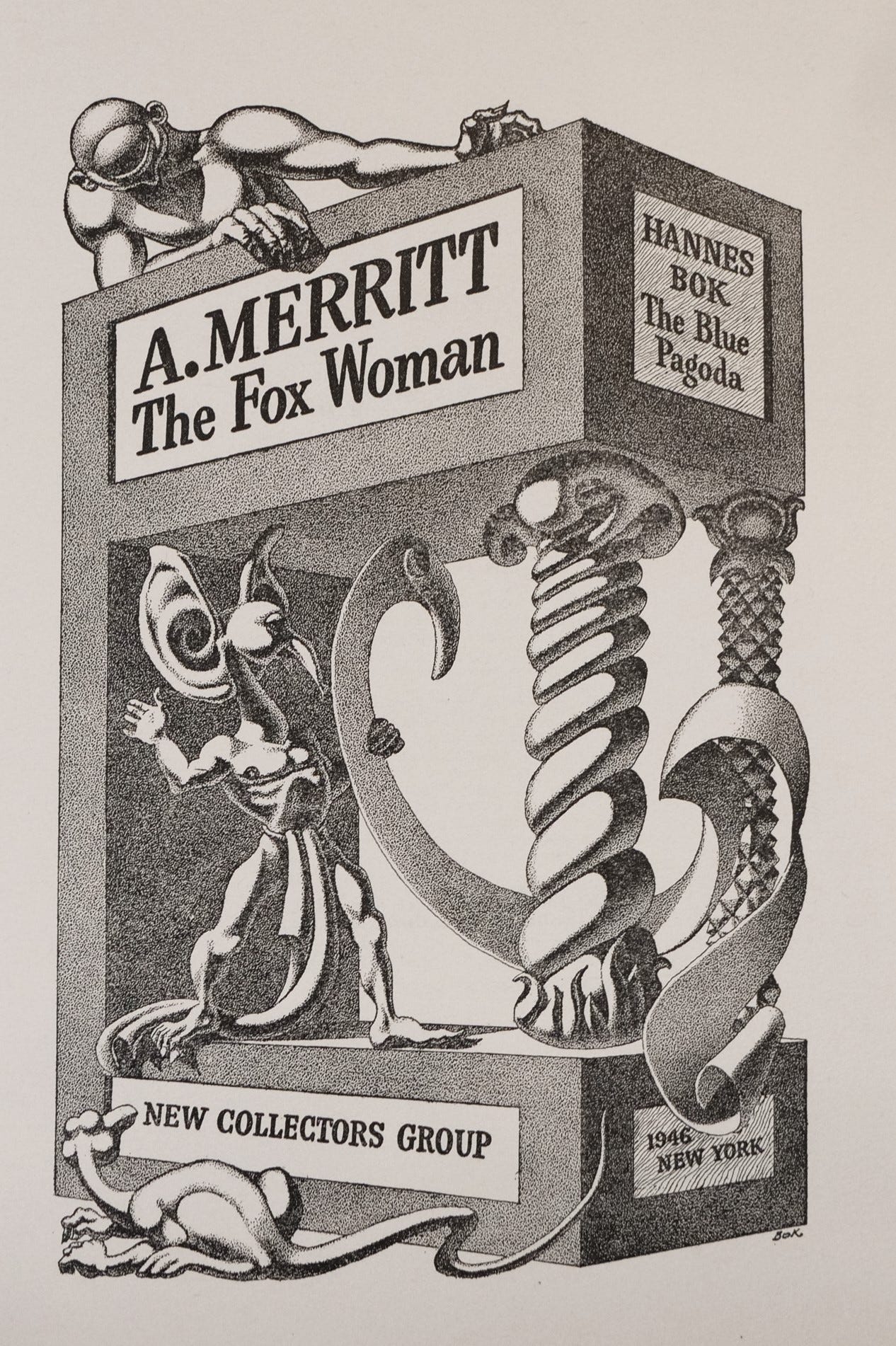

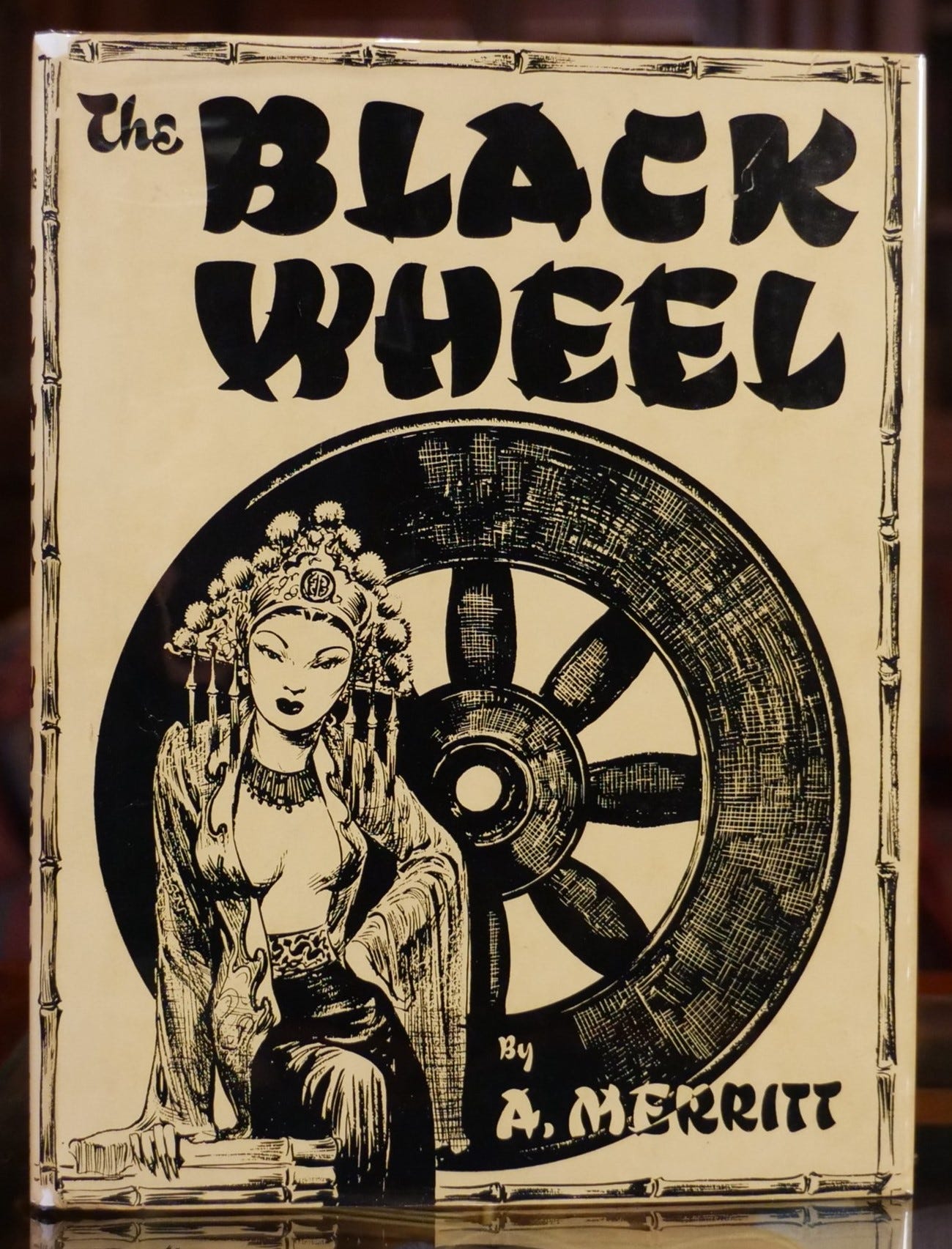

He was a fervent admirer of the fiction of Abraham Merritt, and upon Merritt’s death in 1943, Bok worked to complete two of the author’s unfinished novels–The Fox Woman, for which Bok wrote a concluding story titled The Blue Pagoda, published in 1946; and The Black Wheel, published in 1947. Bok illustrated both books.

He also wrote two dozen works of short fiction, most of which appeared in Bradbury’s Futuria Fantasia, Lowndes’ various pulp magazines, or Weird Tales prior to 1945. Few of them were ever anthologized. A collection of his poetry was published in 1972 under the title Spinner of Silver and Thistle.