Perry Mason exists in the public's imagination as a paragon of lawyerly skill and virtue, based on decades of popular radio, film and television portrayals of the iconic character. But that wasn’t how he was originally written by his creator, Erle Stanley Gardner.

He’s perhaps the most famous fictional trial lawyer of all time—the counsel of choice for criminal defendants with seemingly unwinnable cases. Through ingenuity, cagey lawyering and the help of his legal secretary, Della Street, and private investigator Paul Drake, he emerged victorious almost without fail.

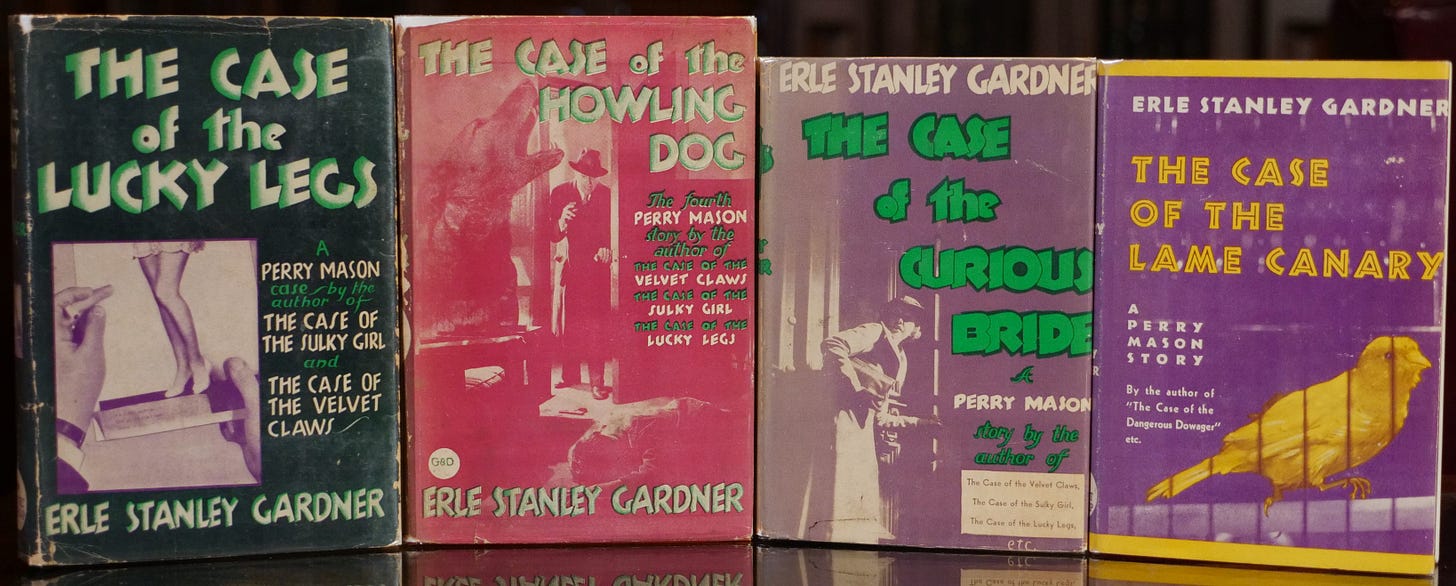

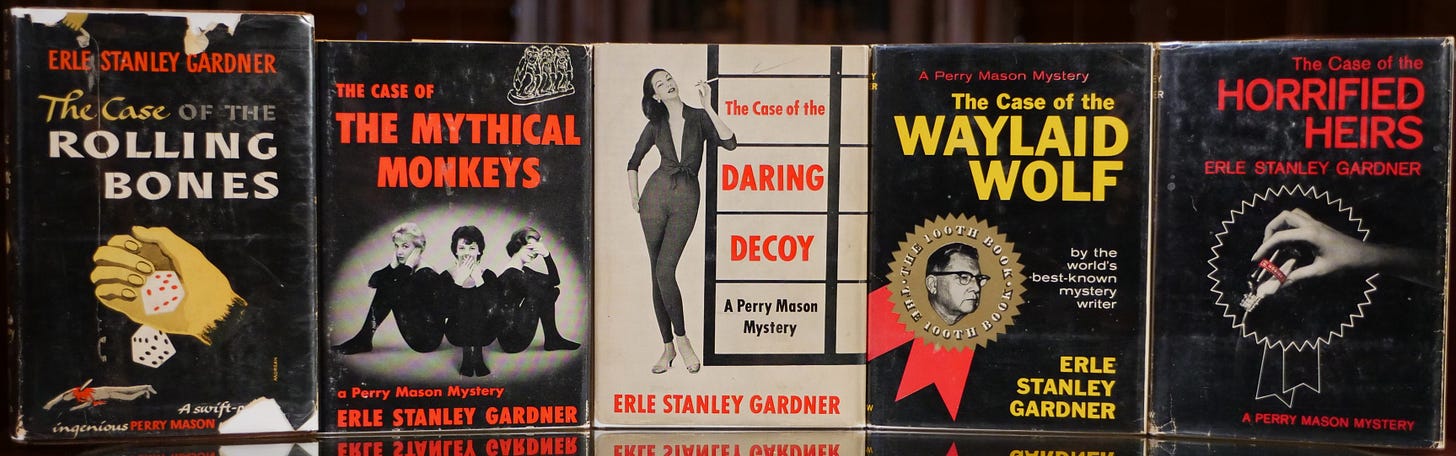

He was created by author Erle Stanley Gardner and made his debut in the 1933 novel The Case of the Velvet Claws. Over the next 40 years, Gardner published 81 more Perry Mason novels, and for several decades it was the bestselling book series of all time. Today it ranks as the third bestselling series ever, behind only the Harry Potter and Goosebumps books.

Gardner's Perry Mason novels were an instant success, with several of his early ones adapted by Hollywood into movies almost as soon as the books were published. A popular radio series featuring the character also aired from 1943 to 1956, after which it transformed into the television soap opera The Edge of Night, airing from 1956-1984 (with the characters’ names changed).

Today, the most popular and enduring image of the character is the version portrayed by Raymond Burr in the eponymous television show that ran from 1957 to 1966 and continues to be watched in syndication almost seven decades later.

Several generations who might not have read Gardner's novels were inspired to pursue legal careers after watching Burr's Mason perform his courtroom wizardry. Countless budding lawyers aspired to have the same confidence, poise, cleverness, ethical rigor and calmly urbane demeanor.

But that version of Mason is a far cry from how Gardner originally wrote the character.

Pulp Fiction Perry

In the books, most of what we know about Mason is gleaned from his actions, rather than from a detailed description of him. Only the very first book, The Case of the Velvet Claws, provides significant clues about how Gardner initially imagined the character.

In it, Mason is described essentially as a street brawler with a law degree. He's burly, physically intimidating, hot-tempered and prone to fisticuffs (or at least aggressive threats to punch someone). He's also ethically very flexible. His approach to representing criminal defendants is almost Machiavellian in his embrace of legally and ethically questionable tactics to win a 'not guilty' verdict for his clients.

He lies to law enforcement authorities. He tampers with evidence and sometimes manufactures false evidence to obstruct police investigations. He bribes authorities for inside information or access to evidence. He engages in improper ex parte communications with judges. He has clear conflicts of interests in his simultaneous representation of multiple persons involved in his cases.

In other words, he's an anti-hero straight out of the crime pulp magazines of that era.

To him, a little misconduct is perfectly acceptable in pursuit of his clients' exoneration. Were he to engage in those kinds of actions today, he would risk his own arrest and disbarment, as well as malpractice lawsuits for his cavalier attitude toward the risks he imposes on his clients.

Despite the risks, Perry does whatever it takes to win his cases, and he rationalizes it by arguing that the police and prosecuting attorneys are more unethical than he is. His operating assumption in the early books is that most law enforcement officials play dirty by manufacturing evidence, coercing confessions, and stacking the deck in various other ways against criminal defendants. He asserts that he's simply leveling the playing field by using similar tactics.

This was a clear expression of the ethos found in many of the crime pulps of that era, which isn't surprising, since Gardner started his literary career writing short stories for cheap crime and mystery magazines such as Gang World and Dime Detective Magazine.

Keep in mind this was decades before landmark legal rulings by the US Supreme Court establishing basic rights for criminal defendants, such as the right to remain silent and the right to have a lawyer present when questioned by police. Police and prosecutorial abuse were common back then.

Gardner had first-hand knowledge and experience with that unfortunate side of the law. In his day job, Gardner was a practicing trial attorney who frequently sought out and represented clients who were poor, illiterate or otherwise unable to defend themselves against a law enforcement process that routinely railroaded them to jail without a fair trial.

In the 1940s, he founded The Court of Last of Resort in Southern California, the first nonprofit organization in the US dedicated to advocating on behalf of the wrongly convicted. It was a precursor to later organizations and initiatives such as The Innocence Project.

Perry’s Character Shift

Over the course of the first decade of the book series, Gardner's Perry Mason character gradually evolved into something more closely resembling his popular image today. Some of that evolution can be attributed to the rising popularity of detective fiction featuring sympathetic and ethical supersleuths created by Golden Age mystery writers such as Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen.

Gardner recognized the trend and embraced it.

Some of the change in Perry’s character might also have been the result of a growing push within the legal profession for stronger ethical standards for lawyers, which Gardner sought to promote.

And some of the transformation likely was an effort to satisfy public expectations created by the movie and radio adaptations of the 1930s and 40s. You see, those film and radio productions reached far larger audiences than the original books on which they were based, so most potential readers of the series were primed to expect book Perry to be much like his portrayal on the silver screen or over the airwaves.

Regrettably, his early film portrayals were not very consistent...or very good...and they differed substantially from the books.

Popular 1930s leading man, Warren William, played Mason in several of the films, and he was badly miscast, in my opinion. I think of Warren William as the American equivalent of English actor Basil Rathbone (who famously played Sherlock Holmes in several films a few years later). Both actors conveyed airs of snooty, cultured elitism, which was a far cry from the rough-and-tumble origins and persona of Gardner's Perry Mason.

Even worse, after the enormous success of the 1934 film adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's The Thin Man, the producers of the Perry Mason films tried to recreate the magic of Nick and Nora Charles by transforming Mason's character into a comical, lovable lush who marries his long-suffering secretary Della Street, who then tries to keep him upright, sober and on track.

The comic twist was a bad fit, and the plots of the films deviate substantially from those of the novels on which they're based. Nevertheless, audiences responded positively, resulting in six Perry Mason films from 1934 to 1937.

Other Character Shifts

Gardner also abandoned the original incarnations of his other main characters.

Della Street, Mason's legal secretary, initially is portrayed in the books as highly intelligent, possessing more people savvy and common sense than Mason. Perry relies on her abilities a lot as she helps him think through problems and assess people and situations. She's like a true partner to Mason.

However, after the first couple of books, Della loses much of her individuality and sense of agency, becoming more of a prop that Gardner and Mason use to advance the plot. I suspect this shift in Della's character was partly influenced by her extremely shallow film portrayals. I also wonder if Gardner worried about showing Mason in a less than perfect light.

Della was an effective foil for Mason's character flaws in the early books, chiding him for his ethical failings and questioning his judgment. But as Mason gradually transformed from a scrappy fighter into a polished superlawyer, it appears that Gardner eliminated those aspects of Della's character that undermined Mason's idealized image.

A similar thing happened to Paul Drake, the private investigator Mason frequently retains for assistance on cases. In the early books, Drake is very independent and somewhat mistrustful of Mason and his legally and ethically dubious practices. Drake doesn't want to lose his investigator's license as a result of Perry’s corner-cutting, so their relationship is far more transactional than friendly.

Again, over time, Drake's character gradually changes to become a regular comrade and compatriot of Mason, sometimes bending the rules on his own in order to keep Perry's hands and reputation clean.

These character shifts culminated in the long-running TV series of the 1950s and '60s, in which Mason is unflappably calm, cool and collected; Della is the supportive, but generally inconsequential, secretary; and Drake is practically a business partner and best friend of Mason.

I grew up watching syndicated reruns of that show, and it formed my initial impressions of the characters. When I later discovered the book series as an adult, I was a little dismayed by his brazen character flaws, particularly in the early books, but I also enjoyed the change of pace, and they gave me a different (and probably more realistic) perspective on the character.

HBO’s 2020 adaptation starring Matthew Rhys as Mason is far closer to the original version of Gardner's character than any other film adaptation. It takes a few liberties with Mason's backstory, history and motivations, filling in some of the gaps in Gardner's very sparse character descriptions. But it also presents Perry as scrappy, combative and flawed, and willing to cut ethical corners to help his clients, much like he is in the early books. The show has a very seedy and pulpy feel to it, which matches his literary origin.

Reading the books

So, are the books any good, and are they worth reading today?

Absolutely!

The mysteries at the heart of most of the books are surprisingly good and well thought out. Many of the books seem like a cross between a modern legal thriller by John Grisham or Greg Iles, a Golden Age locked room mystery by Ellery Queen or John Dickson Carr, and crime stories from the pulp magazines (in their tone, style and dialogue). The early books are more akin to pulpy legal thrillers, while later books often resemble the manor house mysteries of Agatha Christie and the baroque and soapy intrigues of Ross MacDonald.

The basic plots tend to follow a similar formula:

Mason is approached by a prospective client. A murder occurs. The client is accused of the crime and faces overwhelming evidence against them. Mason searches for new evidence to exonerate his client. And a courtroom showdown demonstrating Mason's brilliance concludes the story.

The description of legal procedure and analysis is quite detailed and pretty accurate for the time period. Gardner, through Mason, provides a good primer on the adversarial nature of trial advocacy.

Also, the mystery elements in the books generally follow Ronald Knox's rules of Golden Age mystery fiction, most notably the requirement that readers be presented all the evidence needed to solve the crime on their own. Sometimes, Gardner hides Mason's plans and legal stratagems from readers so that Mason can pull a proverbial rabbit out of a hat in the climactic courtroom scene, but I rarely felt cheated by those tricks by the author. The underlying evidence typically was always available.

Finally, the books can be read in any order. They're essentially standalones, although sometimes with opening and closing paragraphs that connect loosely to the preceding and following books in the series. I recommend starting at the very beginning and reading the first four or five books in the series in chronological order (The Case of the Velvet Claws, The Case of the Sulky Girl, The Case of the Lucky Legs, The Case of the Howling Dog, and The Case of the Curious Bride) to get a good sense of where Perry Mason started as a character. From there, feel free skip around in the series.

They’re fun, quick reads that make a great change of pace between longer and weightier tomes commonly found in other genres.

I'll be featuring more classic mystery authors and stories in future posts.