Shasta Publishers: The Little SF Press That Could

In videos I made for my YouTube channel a couple of years ago, I traced the histories and impact of Gnome Press and Arkham House, two of the most influential small publishers of all time. Those tiny presses are legendary today for their pivotal roles in popularizing the science fiction, fantasy and horror genres in the mid-20th century. They helped some of the most famous authors in the histories of those genres—Asimov, Heinlein, Clarke, Bradbury and Lovecraft, among others—escape the disreputable confines of pulp magazines and reach wider, mainstream audiences.

The 1940s and 50s saw the rise (and demise) of many small publishers that left their marks on speculative fiction. In almost every case, they were passion projects led by enthusiastic fans rather than well-planned and well-capitalized business ventures.

Arkham House was one of the first, and Gnome Press was the most prolific, during that two-decade period before competition from cheap paperbacks and Doubleday’s Science Fiction Book Club drove most of those pioneering presses into bankruptcy.

However, one tiny publisher, the brainchild of a group of teenaged pulp magazine collectors, came very close to achieving the kind of lasting success that could have served as a model for other small presses.

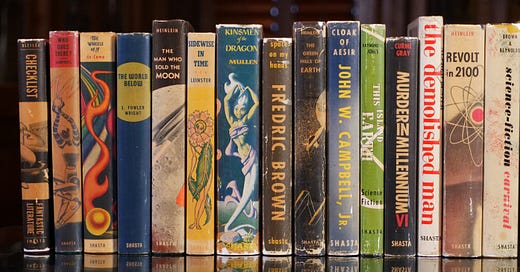

Shasta Publishers, founded in 1947, printed only 19 titles in its nine-year history, but the lack of quantity was more than offset by the quality of the works.

Among them were:

the first three volumes of Robert Heinlein’s highly influential Future History series;

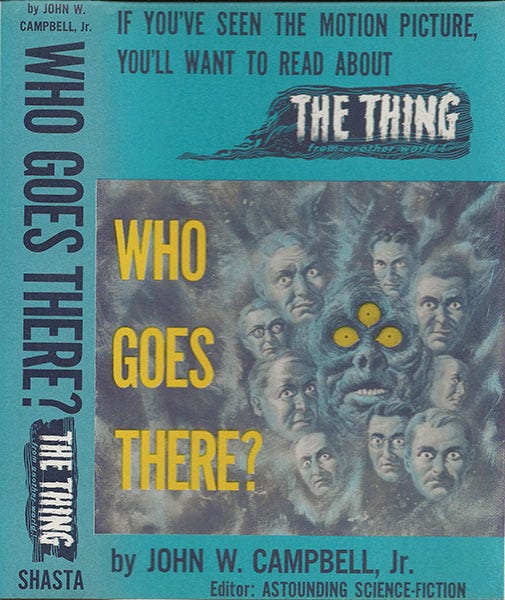

two collections of short fiction by legendary editor John W. Campbell, including the story ‘Who Goes There?’ that was adapted for film multiple times as The Thing;

the novella that essentially created the alternate history subgenre;

the winner of the first ever Hugo Award for best novel; and

perhaps most consequentially, the first comprehensive bibliography of English language science fiction, fantasy and weird fiction published prior to 1949.

Six of the books had iconic dust jackets designed by Hannes Bok, the winner of the very first Hugo Award for best cover artist.

[Note: The sixth book (not pictured) is L. Ron Hubbard’s Slaves of Sleep. I discuss Hannes Bok’s artwork and career in another essay here.]

Most of Shasta’s books reprinted noteworthy speculative fiction at risk of being forgotten because it had appeared previously only in pulp magazines with a short shelf life. A few, though, were original works published for the first time.

Their publication in hardcover format gave those authors and works credibility and marketability the pulps couldn’t, enabling them to reach wider audiences, mainly through public libraries, which were target customers of small presses such as Shasta.

Unlike the large publishing houses that dominated the market, Shasta lacked the working capital and sales and distribution infrastructure needed to supply a nationwide network of booksellers and department stores. Instead, it produced only small print runs of 1,500-5,000 copies of each title, and prioritized libraries as a reliable way to maximize their exposure to a broad range of readers.

It also had a mail-order option for speculative fiction fans, which it advertised in the pulp magazines.

Shasta’s Origins

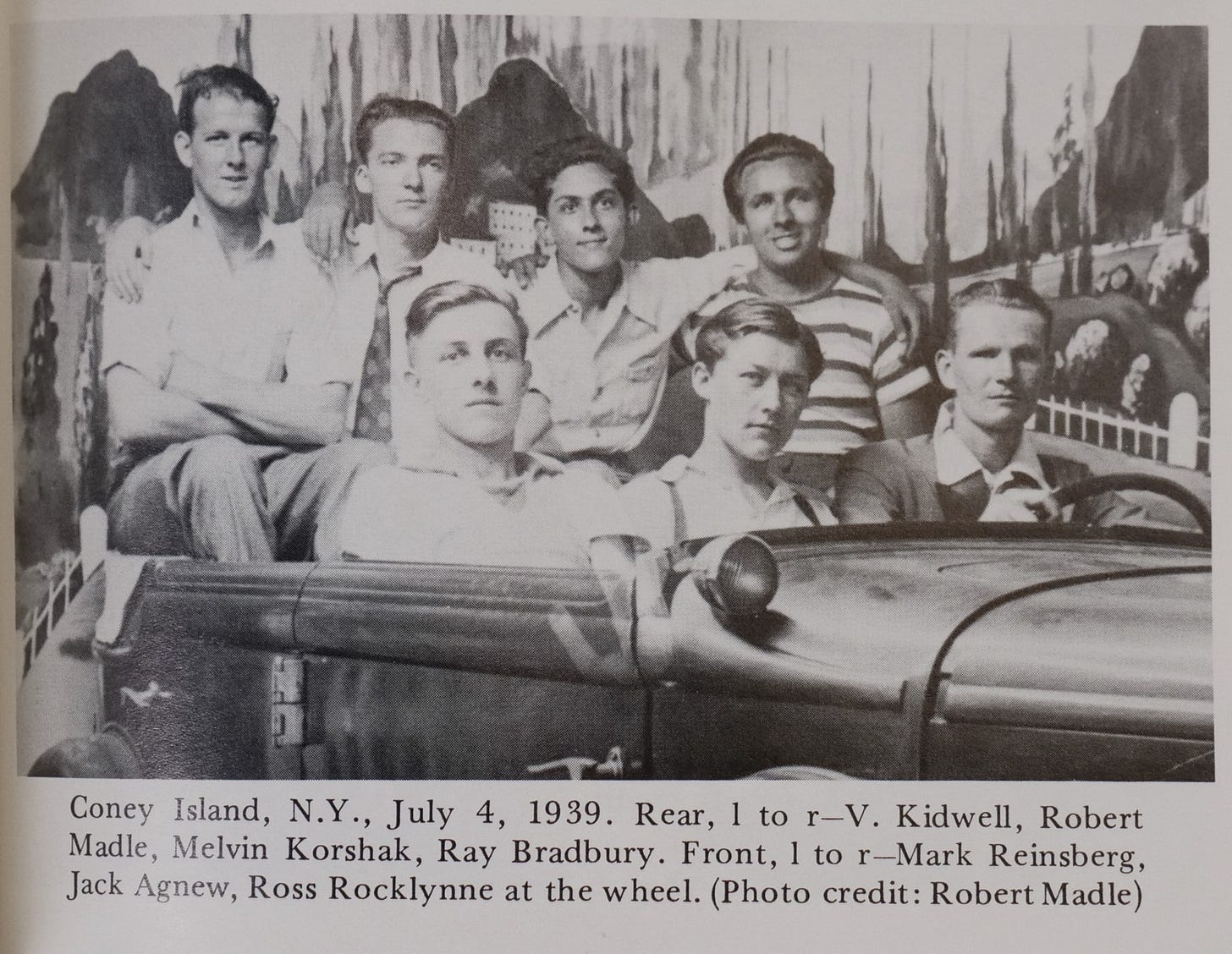

In the summer of 1939, two Chicago teens, Mel Korshak and Mark Reinsberg, traveled to New York to attend the very first World Science Fiction Convention, or Worldcon. Along the way, they stopped to visit two Indiana acquaintances, Ted Dikty and Fred Shroyer, who were SF fans as well. Three of them were teenagers, with Korshak the youngest at 16, while Shroyer was the oldest at 23.

Korshak was an entrepreneur. An avid collector of science fiction, fantasy and horror titles from an early age, he had financed his own extensive SF collection through a successful side hustle reselling used speculative fiction books and magazines to other collectors. He was organized and methodical in the mail-order business he ran, advertising in Chicago-area newspapers and printing catalogs of his inventory that eventually found their way to collectors in other parts of the country – all by the time he was 15 years old.

Nineteen-year-old Ted Dikty had been an SF collector since he was nine, when he began saving his money to acquire back issues of his favorite pulp magazines. His dedication to the task was impressive. He walked home from high school 25 blocks rather than ride the streetcar, because it allowed him to visit the thrift shops, Salvation Army, and furniture and clothing stores along the way, where he could salvage discarded magazines. He also was an occasional correspondent and customer of Korshak’s mail-order business, which is what led them to get together that summer with Reinsberg and Shroyer.

During that fateful visit, the young men lamented the lack of a list or index of published speculative fiction works they could use to help them build their collections. How would they know what authors and titles to look for, or what magazine back issues contained them, without a comprehensive index to use as a reference guide?

Keep in mind that pulp magazines at the time generally were considered cheap, disposable entertainment for the lower classes. Libraries didn’t include them in their collections, and many of the magazines’ publishers operated on shoestring budgets without the staff or desire to maintain or publish detailed bibliographic records. In many cases, once a pulp magazine issue was published, it was largely forgotten by the publisher as its attention turned to producing the next issue.

Over the next few months, the four youths decided to create such an index on their own. They wrote letters to other SF fans and to literary magazines such as the Saturday Review of Literature asking for help, seeking lists of authors, titles and publication histories.

The responses they received were encouraging, and by 1941, they had amassed a shoebox full of index cards and other notes. They had to shelve the project, though, while the four of them served in the military during World War Two.

After the war, Korshak and Dikty were eager to resume work on the index, but the shoebox and notes, which had been stored in Dikty’s home, were nowhere to be found—the victim of an overzealous house cleaning while he was away.

Undaunted, they started over, sending out new rounds of letters to fans and publications seeking their input. They also had their own impressive book and magazine collections from before the war to use as a starting point.

They were aided in this effort by Shroyer, who supplied more than 2,000 index cards documenting his own extensive collection, most of which he acquired in bulk at the end of the war from English-language bookshops in Japan that still had plenty of old inventory after being closed for years.

Korshak resumed his used bookselling business in Chicago, and Dikty joined him as a partner in the venture. By 1947, they were a success, but they struggled to find time to work on their checklist of fantastic literature, which is what they were calling their indexing effort.

Enter Everett F. Bleiler, a hardcore speculative fiction fan and graduate student in anthropology at the University of Chicago, who met Korshak and Dikty through their bookselling efforts. His academic background had taught him bibliographic skills that the others lacked, and he offered to help compile and organize the checklist.

Before long, Korshak and Dikty put him in charge of the project as its editor.

Around that time in 1947, Shasta Publishers was founded by Korshak and Dikty to produce the checklist. The fourth original collaborator, Mark Reinsberg, participated in the planning of Shasta’s launch and even suggested the company’s name, but he decided to pursue a career in academia instead of joining them as a partner.

By this point, their speculative fiction indexing project had become more than just an attempt to catalog titles and publications for other collectors and booksellers. As Korshak put it in his preface to the Checklist of Fantastic Literature when it was published in early 1948, the effort served four purposes:

to assist speculative fiction readers, collectors and booksellers in identifying and locating such works;

to help librarians more accurately classify works of speculative fiction;

to serve as a resource for research scholars and literary historians studying the evolution of fiction and its impact on society; and

to provide psychologists with suggestions for using fantastical fiction as a tool in psychoanalysis, replacing dream analysis as means of revealing unconscious mental processes.

That last one might have raised some eyebrows.

All told, around 70 people contributed information for Bleiler to compile and organize, including listings of the holdings of major collections and records from the US Library of Congress and the British Museum.

Owing to the significance of Shasta’s efforts, the Library of Congress later recognized the Checklist for its “lasting contribution to American letters in the field of the humanities.”

Not bad for a project started by a few teenaged fans.

[Side note: For more information about the Checklist of Fantastic Literature, see my related essay about the roots of the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (isfdb.org) linked here.]

The Checklist also was a financial success — a rarity for small publishers at the time. Shasta kept its production costs low by not having to pay royalties to an author (Bleiler was paid a modest fee for his editorial efforts) and by using a cheap, local printing company with no experience in bookbinding.

The printing company was nearly a disaster for Shasta. Its printing press was an antiquated model that used jets of flame to dry the ink on the pages. With alarming frequency, pages would ignite, and only a little over 1,900 of the 2,200 printed copies survived the process.

[Note for collectors: In a money-saving effort, Shasta initially bound only the first 1,000 copies from that print run and held off binding the remaining 900+ to see if the first batch would sell. It sold quickly and a month later Shasta bound the remaining copies for sale. The second batch was listed as a second printing on the book’s copyright page, but in reality, those copies were part of the initial print run.]

Despite the fire-related losses, Shasta cleared a profit of almost $8,000 on the Checklist, which gave Korshak and Dikty the working capital to lease office space, to find a better printing company, and to begin publishing works of speculative fiction by some of their favorite authors.

The First Pivot

Although originally intended simply as a vehicle for publishing the Checklist and similar reference guides for collectors, Shasta pivoted rapidly in 1948 to works of fiction, perhaps inspired by the post-war proliferation of small presses such as Fantasy Press, FPCI, Prime Press, Hadley Publishing, Buffalo Book Company, and the New Collectors Group that specialized in speculative works. (Gnome Press didn’t arrive until 1948; however, its founders were friends of Korshak and Dikty and might have influenced Shasta’s pivot.)

By the end of 1948, Shasta had published John W. Campbell’s Who Goes There?, a collection of short fiction originally published in Astounding magazine in the 1930s under Campbell’s pseudonym Don A. Stuart, as well as the L. Ron Hubbard novel Slaves of Sleep, which had first appeared in Unknown magazine in July 1939. A second printing of Who Goes There? in 1951 changed the dust jacket to capitalize on the popularity of the film adaptation of the title story that year.

Two more books followed in 1949: L. Sprague de Camp’s short fiction collection The Wheels of If, and S. Fowler Wright’s The World Below, an omnibus edition of his science fiction novels The Amphibians (from 1925) and the title story (from 1929).

Due to the prominence of the authors, and Korshak’s and Dikty’s previous experience advertising and selling books by mail order, each title sold well, leading Shasta to increase its print run sizes for each title. But the company needed more capital to keep growing.

Late in 1948, Dikty and Everett Bleiler came up with the idea of publishing an anthology of SF stories they considered to be the year’s best. They wanted Shasta to publish it, but the company didn’t have sufficient resources at the time. So instead, they turned to Frederick Fell, a small publisher of self-help books and how-to manuals with no experience in speculative fiction, for help.

Frederick Fell saw an opportunity to enter a new market and agreed to publish the anthology, splitting the proceeds with Dikty, Bleiler and Korshak. Bleiler pocketed his share while Dikty and Korshak invested theirs back into Shasta to strengthen its balance sheet.

Thus was born an influential series of twelve Year’s Best SF anthologies published by Frederick Fell and edited by Dikty and Bleiler jointly or individually over the next decade that provided financial support to Shasta.

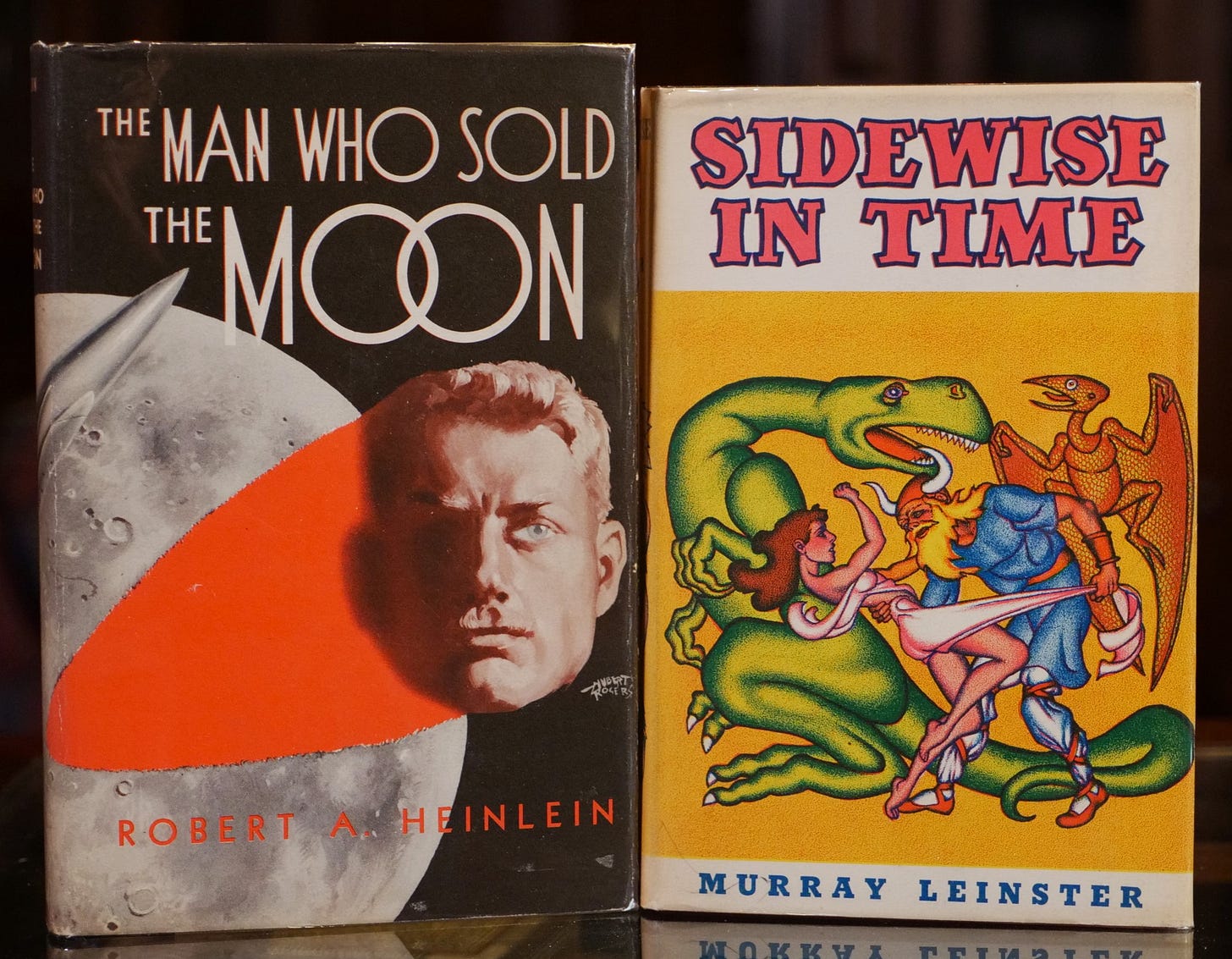

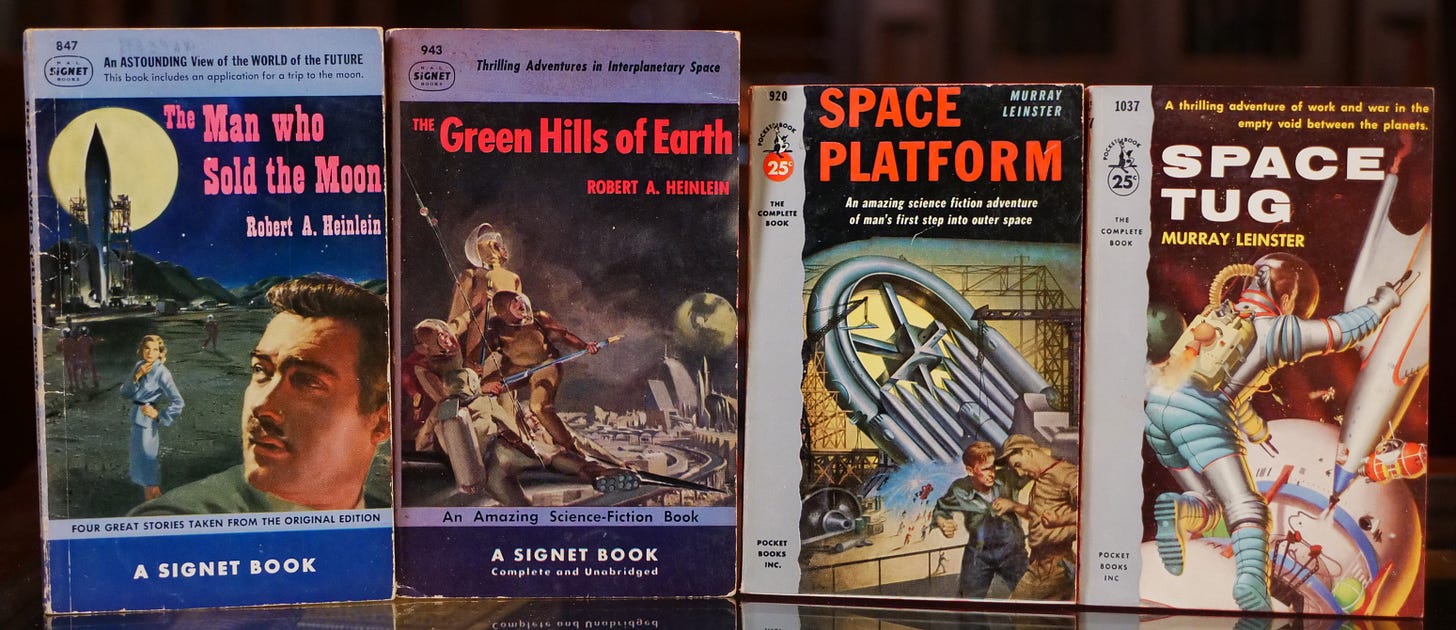

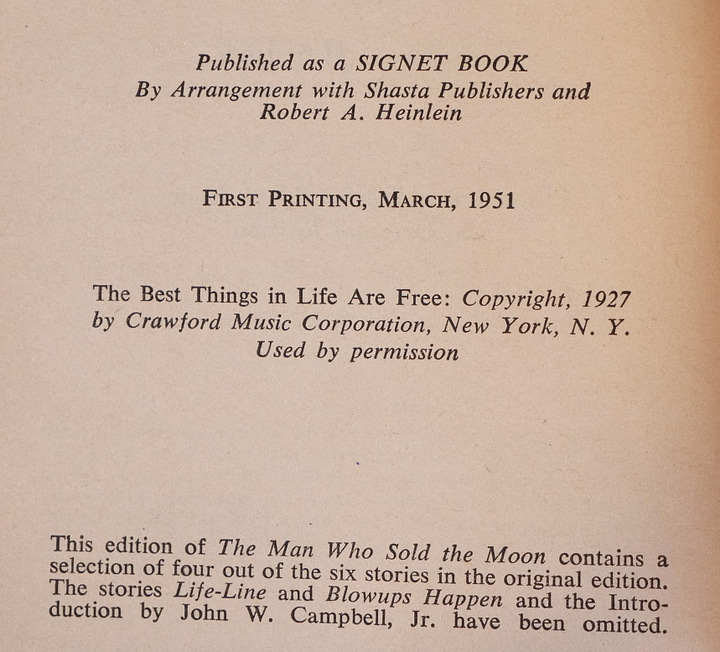

With a fresh infusion of cash from the first Frederick Fell anthology, Shasta launched its highest-profile effort to date – publishing the first hardcover editions of Robert Heinlein’s Future History series of stories, beginning with The Man Who Sold the Moon in 1950. This widely praised collection of short stories, most of which were published in the pulps a decade earlier, contains classics such as ‘The Roads Must Roll,’ ‘Requiem,’ and the title story.

Getting a multi-book commitment from Heinlein, perhaps the most popular SF author at that time, was a real coup for Shasta. (Heinlein’s doubts about Gnome Press’s business practices following its publication of his novel Sixth Column in 1949 might also have influenced his decision.)

1950 also saw Shasta publish Sidewise in Time, a collection of science fiction short stories by Murray Leinster from the 1930s and ‘40s, including famous works such as ‘A Logic Named Joe’ and the title story. The Sidewise Award for Alternate History given out each year at Worldcon alongside the Hugos takes its name from Leinster’s story.

The following year, Shasta published three titles:

a fantasy novel by Stanley Mullen, The Kinsmen of the Dragon, that might be most noteworthy for its stunning dust jacket by Hannes Bok;

an excellent collection of short stories by science fiction and mystery author Fredric Brown titled Space on My Hands; and

the second collection of stories in Robert Heinlein’s Future History series, The Green Hills of Earth.

1952 saw three more titles published:

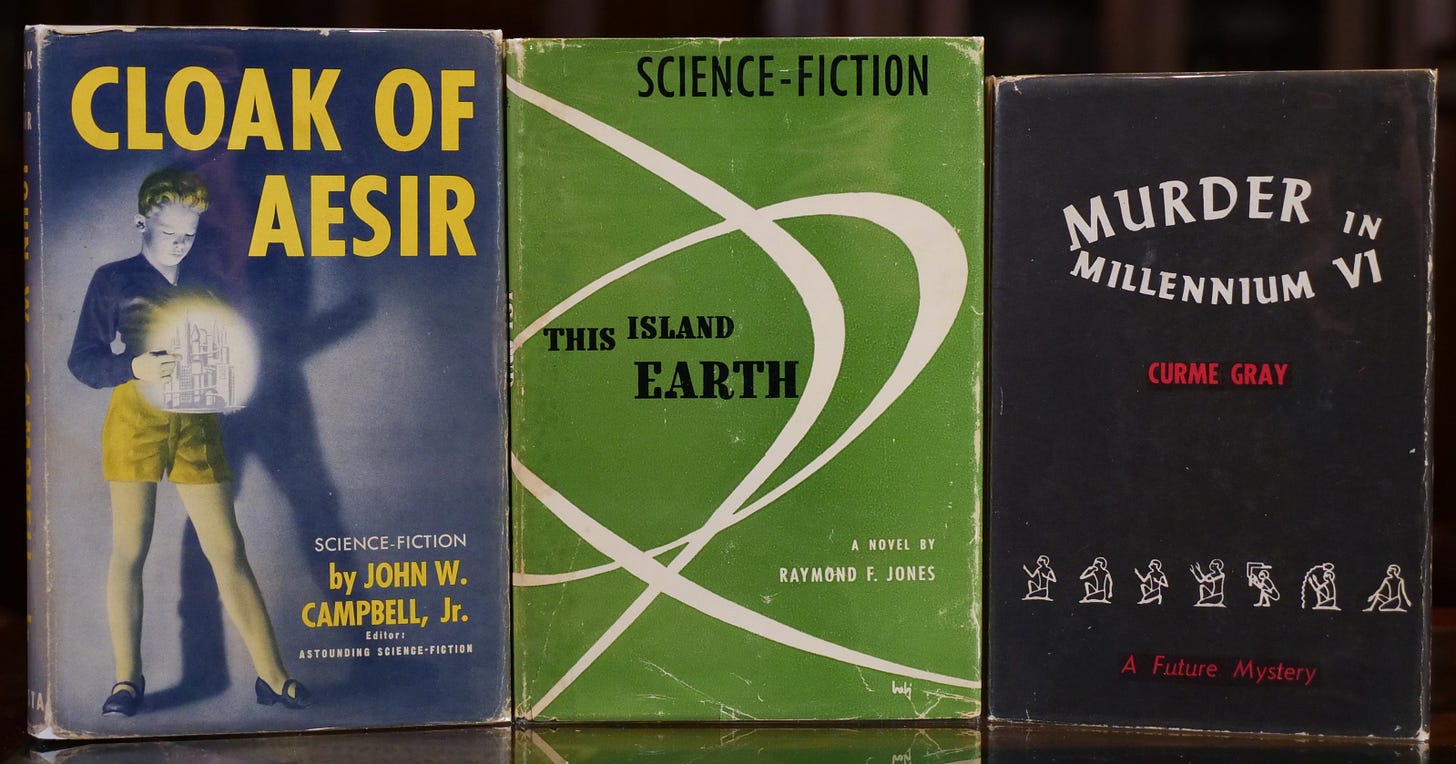

John W. Campbell’s short fiction collection Cloak of Aesir featuring seven more of his best stories previously published in his own Astounding Science Fiction magazine;

Raymond F. Jones’ influential novel This Island Earth, a fixup of three novelettes published in Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1949 and 1950. The novel features Earth as a galactic backwater caught up without its knowledge in a pan-galactic war between alien civilizations. It was loosely adapted into the 1955 film with the same name; and

Curme Gray’s Murder in Millennium VI, a mystery novel set thousands of years in the future that experiments with its narrative form, challenging mystery readers and SF readers alike by bucking conventions of both genres. This is the scarcest title Shasta published, as only 1,500 copies were printed, but copies of it are surprisingly easy to find, due to its relative obscurity.

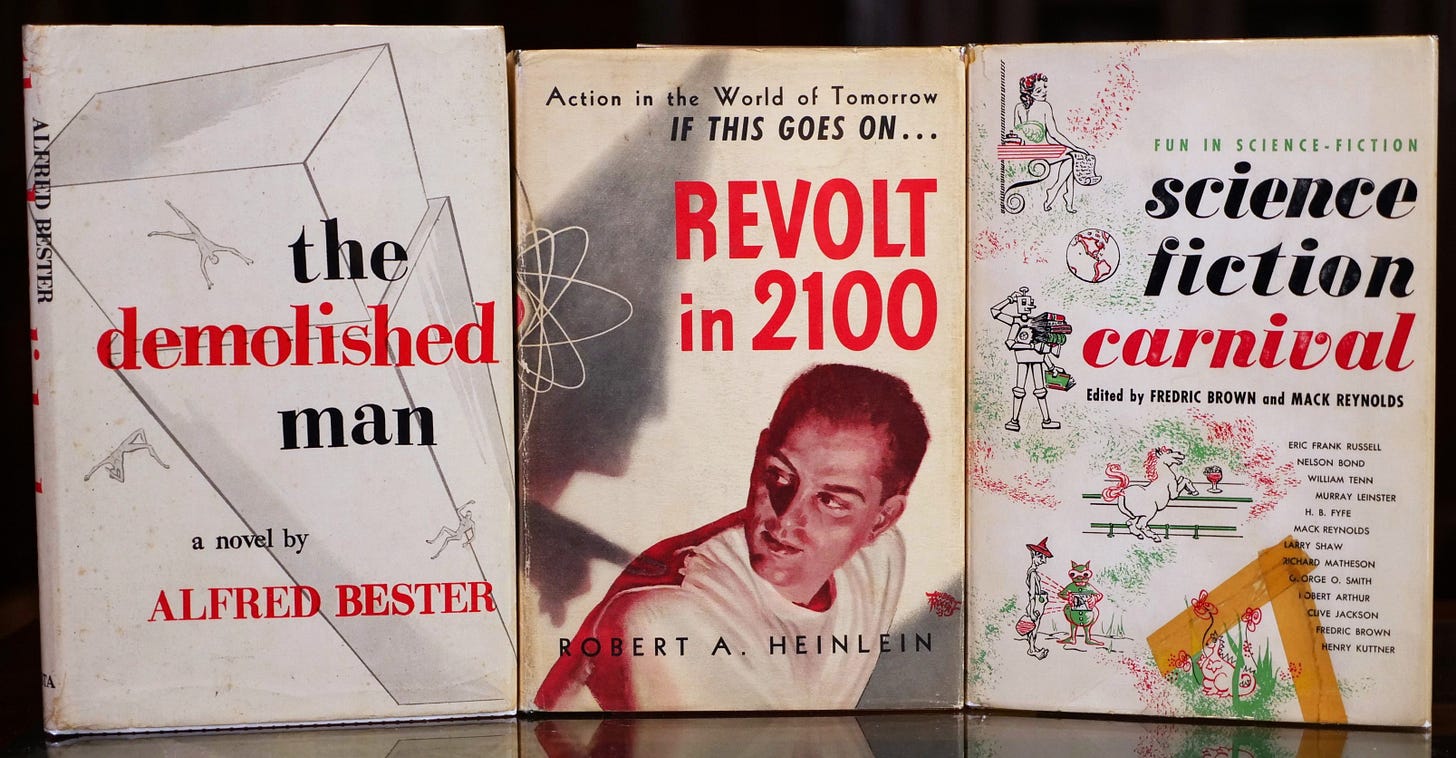

1953 was Shasta’s most productive year, but it also marked the beginning of the end for the company. Alfred Bester’s Hugo Award-winning classic The Demolished Man started the year off with a bang. An initial print run of 3,000 copies was followed soon after by a second printing of another 2,000.

Four more titles followed later that year:

Revolt in 2100, the third volume in Heinlein’s Future History series. It contains the short novel ‘If This Goes On—’ and two novelettes that document an American theocracy in the year 2100 and the aftermath of its demise.

Science Fiction Carnival, a wonderful anthology of humorous SF stories compiled and edited by Fredric Brown and Mack Reynolds. Noteworthy authors featured in it include Brown, Richard Matheson, William Tenn, Eric Frank Russell and Henry Kuttner.

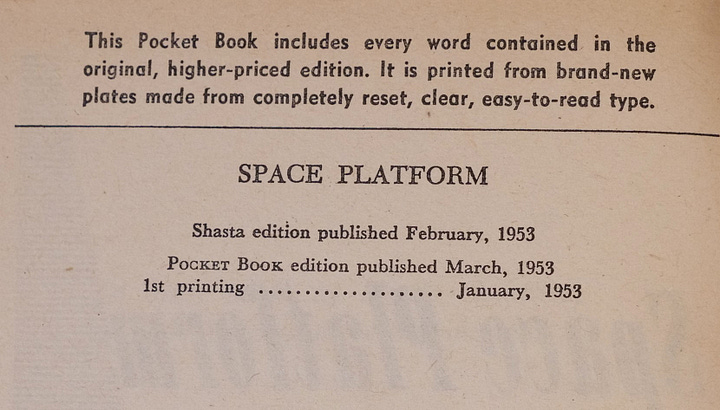

And the first two novels in Murray Leinster’s To the Stars series, Space Platform and Space Tug, aimed at teenaged readers. The books imagine the nuts and bolts of building and supporting a space station in Earth orbit as part of a Cold War space race with the Soviet Union.

However, despite its seeming success, Shasta was struggling financially. The launch of Doubleday’s Science Fiction Book Club in 1953, offering low-priced hardcover reprints using the same printing plates and dust jacket designs as the originals, expanded the visibility and reach of the SF genre, but reduced demand for Shasta’s higher-priced first editions.

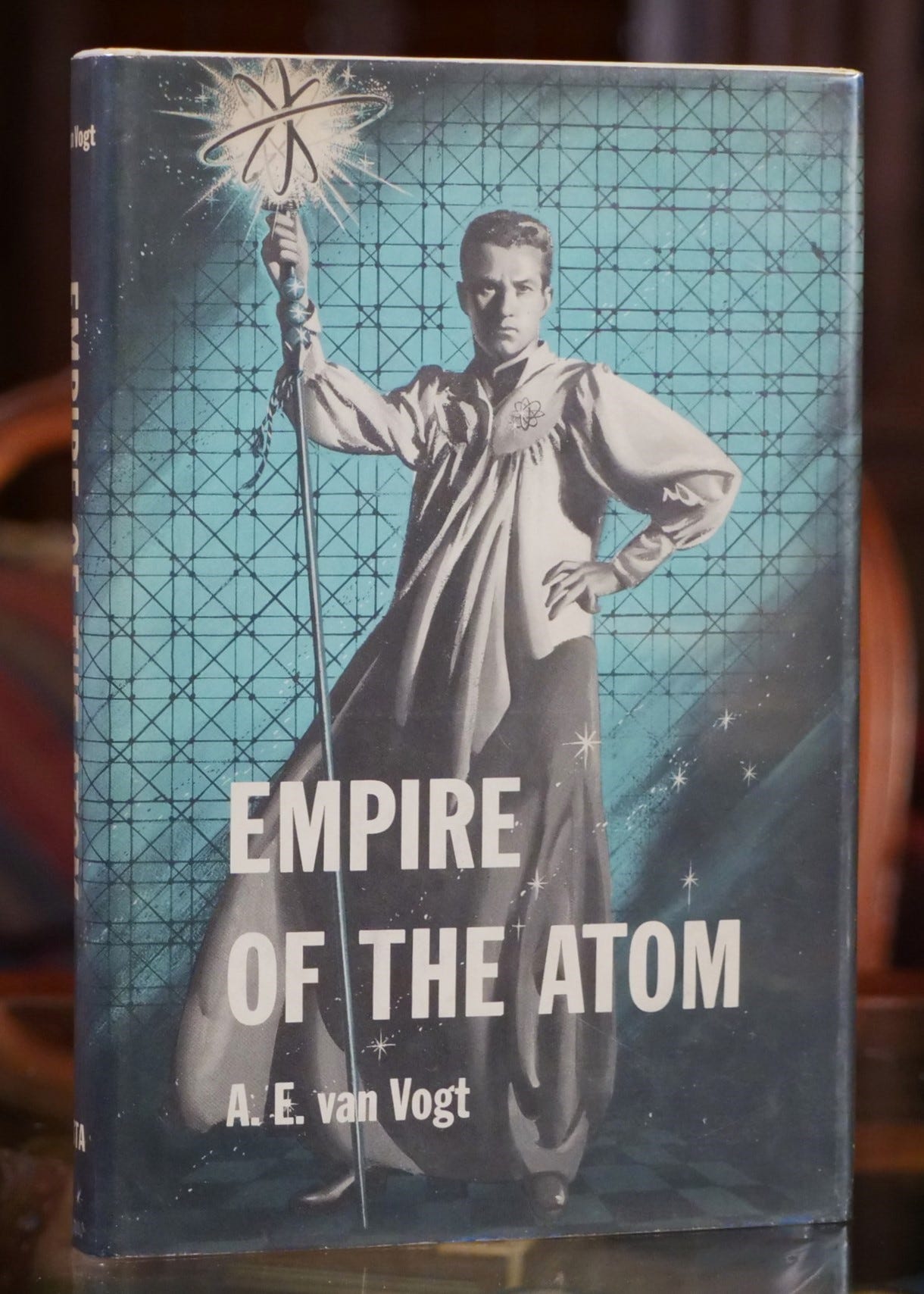

Three of Shasta’s titles were reprinted as book club editions – This Island Earth, The Demolished Man, and A.E. Van Vogt’s fixup novel Empire of the Atom (the final Shasta title published in 1957).

Shasta sold 4,000 copies of This Island Earth, but Doubleday’s nearly identical book club edition a year later far surpassed that amount. Shasta received modest royalties from Doubleday, but had to pass most of them along to the books’ authors, leaving Shasta very little.

Compounding Shasta’s difficulties was the emergence of even lower cost competitors—paperback books. Shasta licensed some its titles to paperback publishers such as Signet and Pocket Books, but the royalties it received in return were a pittance, given the 25-cent cover price of the paperbacks.

The Second Pivot

Squeezed from both ends of the SF publishing market in 1953, Korshak and Dikty recognized the likely unsustainability of Shasta’s small mail-order business model. Unlike their peers at Gnome Press and Fantasy Press, though, who doubled down on their original plans while aggressively cutting costs and deferring bill and royalty payments, Shasta pivoted to a larger dream.

Korshak and Dikty concocted an ambitious plan to transform Shasta into a mainstream publisher.

In 1954, Shasta had several speculative fiction titles in its pipeline, including two more volumes in Heinlein’s Future History; novels from Leinster, Van Vogt, Poul Anderson and Jack Williamson; the original version of Philip Jose Farmer’s Riverworld novel that later became To Your Scattered Bodies Go; and a Guide to Imaginative Literature, Everett Bleiler’s follow-up to Shasta’s 1948 Checklist.

Shasta slowed development of those projects and devoted most of its time and resources over the next two years to publishing a large-scale, high-profile project unlike anything it had previously attempted.

Specifically, a glossy, full-color, large-format beauty book for women authored by five members of the Westmore family, who were among the most famous hair stylists and makeup artists in Hollywood history.

The Westmore Beauty Book was intended to be the definitive guide to makeup and beauty standards, serving as an essential reference book for women and beauty shops nationwide. It was also the kind of prestige project that would announce Korchak and Dikty’s arrival as respected, professional publishers capable of operating in mainstream areas like the large trade publishing houses.

By the time the book was ready in 1956, with around 25,000 copies printed and distributed, they had sunk more than $60,000 into its production, some of it borrowed from friends such as literary historian Sam Moskowitz.

Pre-orders from retailers were encouraging, and an extensive marketing and promotion campaign was planned. Alas, their good fortune failed at the worst possible time. Just as the marketing campaign began its rollout, one of the authors, Perc Westmore, who was to lead the promotion effort, became ill and had to cancel many of the television and public appearances that were the core of the campaign. Without that publicity, retail sales of the book underperformed badly, and they didn’t come close to recouping their up-front costs.

It was a daring gamble that almost paid off. With better luck at its launch, the beauty book likely would have yielded a handsome profit for the Shasta team, giving them the working capital to cover their debts and to begin publishing a dozen more general interest nonfiction works they had already lined up in addition to their planned SF ones.

Technically, The Westmore Beauty Book wasn’t published by Shasta. A separate company, Melvin Korshak: Publishers, was formed to produce the Westmore book, but the overlap between the companies meant that Shasta no longer had the cash or creditworthiness to resume publishing the SF works in its pipeline.

Of the 13 or so SF manuscripts Shasta had previously committed to publish, it managed to print only one — A.E. Van Vogt’s Empire of the Atom in 1957, after which Korshak and Dikty shuttered the business.

As for the rest, Heinlein returned to Gnome Press to publish the next two Future History volumes, The Menace from Earth and Methuselah’s Children in 1957 and 1958. Leinster’s third novel in his To the Stars series, City on the Moon, was picked up by Avalon Books in 1957, and A.E. Van Vogt’s The Wizard of Linn was eventually published as an Ace paperback in 1962. Bleiler’s sequel to the Checklist was never published.

Aftermath

Ted Dikty continued working as an anthologist for other publishers over the years. After marrying avid SF fan Julian May in 1953, they collaborated on activities and events aimed at building the fan base for speculative fiction. May also achieved lasting renown as a science fiction author decades later for her Pliocene Era series, starting with the 1981 novel The Many-Colored Land.

Ted Dikty and Julian May, 1951

I’m not sure of the path Mel Korshak took after Shasta’s demise. It seems likely he returned to his roots selling used SF books and magazines to collectors.

Checklist and anthology editor Everett Bleiler began working at Dover Publications in 1955 and eventually became its editor and executive vice president. While there, he led Dover’s efforts in the 1960s and ‘70s to publish the works of early horror, fantasy, and detective fiction authors such as J. Sheridan Le Fanu, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, Ernest Bramah, R. Austin Freeman and Jacques Futrelle. In the 1990s, he co-authored with his son Richard a massive historical bibliography of early science fiction that greatly expanded on his work for Shasta. It’s considered one of the definitive reference guides for SF collectors and researchers.

Today, Shasta titles are highly collectible. Their historical significance to the development of the science fiction genre, their scarcity, and their eye-catching jackets have made many of them high priorities for enthusiasts and collectors alike. Over the past 25 years, I’ve been fortunate to find 15 of Shasta’s titles in great condition. I still have hopes of finding the other four titles.