Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories created a template that many of his contemporaries sought to imitate with their own brilliant, eccentric detectives who rely on the powers of careful observation, logic and ratiocination to solve dastardly crimes.

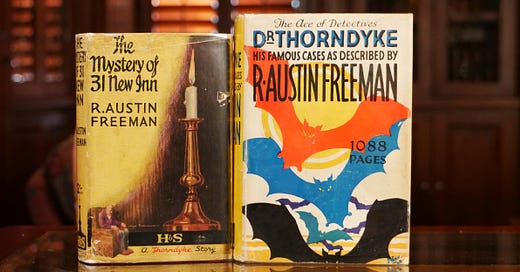

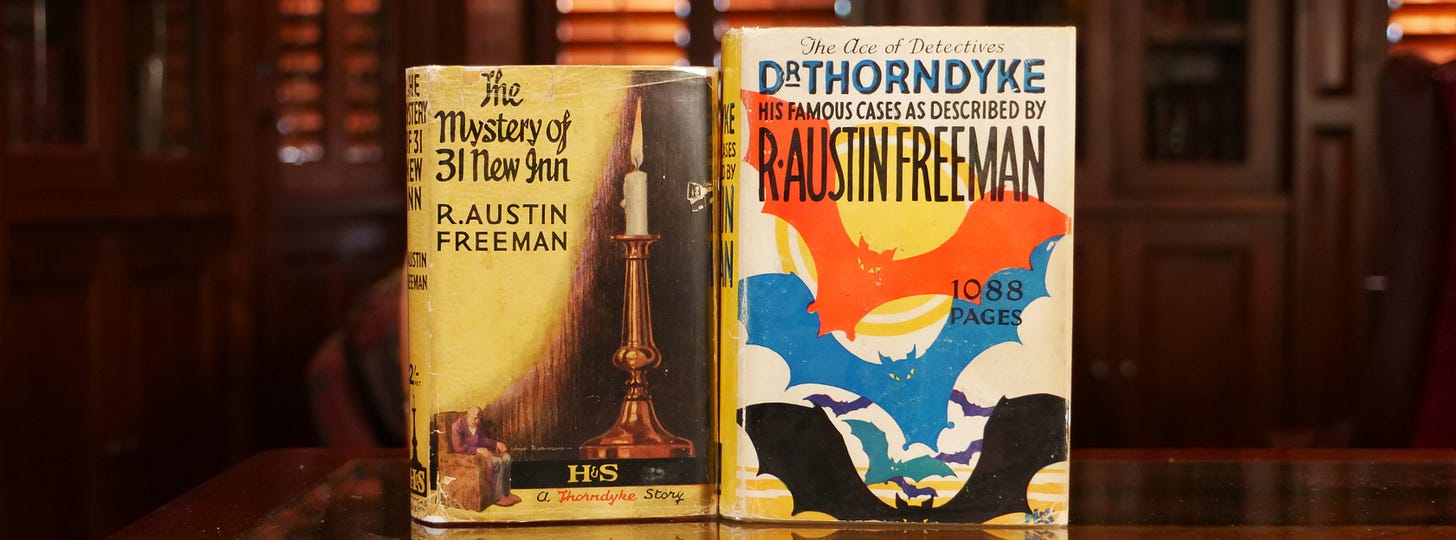

One of the very best was Dr. John Thorndyke, who first appeared in author R. Austin Freeman’s 1905 novella 31, New Inn (that was expanded to novel length in 1912). Freeman published twenty more novels and 40 short stories featuring Dr. Thorndyke between 1907 and 1942.

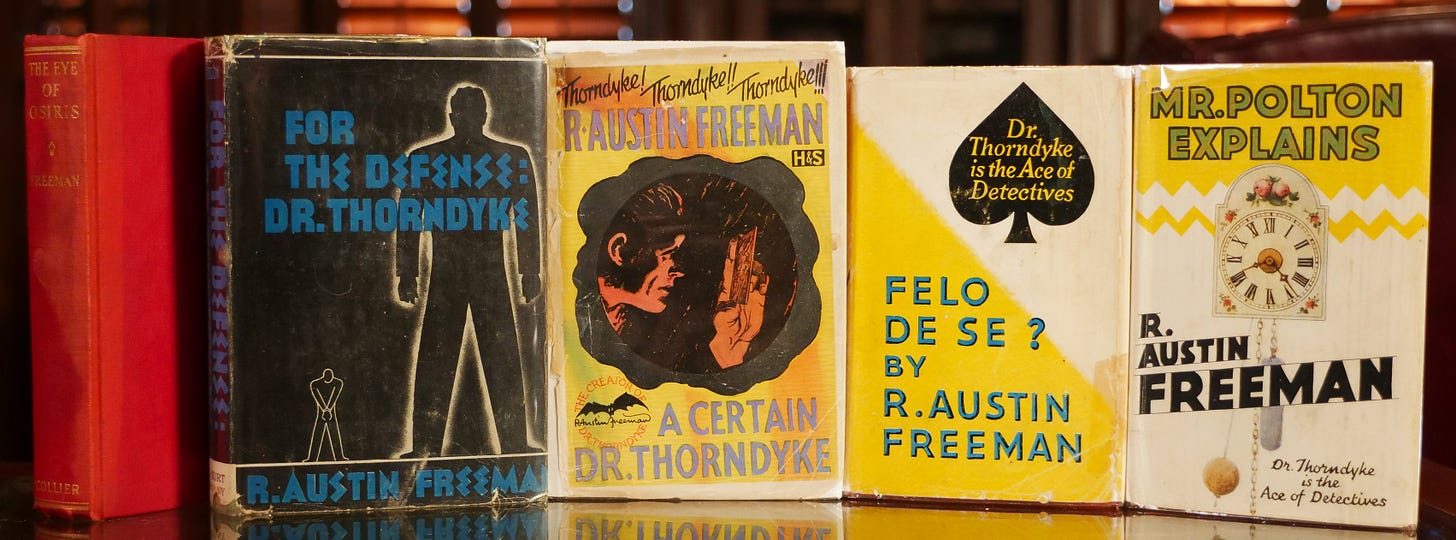

Like Holmes, Thorndyke was a polymath, having studied medicine and law before pursuing a career as a private detective and expert witness for the defense in criminal cases. Both detectives were brilliant pioneers and advocates of modern forensic detection methods, but Thorndyke was the smarter of the two. Doyle was content to provide Holmes with plausible solutions to his mysteries that often were supported by questionable facts, assumptions and leaps of logic. In contrast, Freeman made sure his solutions were backed by facts and proven science.

The author maintained a fully equipped laboratory on the top floor of his home that mirrored Thorndyke’s fictional lab in the stories. Every scientific test or experiment conducted by Thorndyke was first performed by Freeman to prove its validity. In that way, Freeman brought greater scientific rigor to his stories than Doyle, despite both being medical doctors and scientists by training.

Freeman also is credited with pioneering the concept of an ‘inverted’ detective story—one in which the reader learns the identity of the criminal and the method of the crime at the beginning of the story, while the central mystery revolves around how the detective will find and piece together the clues to catch the culprit. As Freeman wrote in the preface to the 1929 omnibus collection of Dr. Thorndyke short stories The Famous Cases of Dr. Thorndyke:

The one essential [element of a Detective Story] is a problem, the solution of which shall afford the ingenious reader an agreeable exercise in intellectual gymnastics. But in order to attain this result, the Detective Story must conform to three indispensable conditions: 1. The problem must be susceptible of…solution by the reader; 2. The solution offered by the author through the official investigator must be absolutely conclusive and convincing; 3. No material fact must be withheld from the reader. All the cards must be honestly laid on the table before the solution is announced.

Consideration of these conditions, and especially of the last, suggested to me, many years ago, an interesting question. “Would it be possible…to write a Detective Story in which, from the outset, the reader was taken entirely into the author’s confidence, was made an actual witness of the crime and furnished with every fact that could be used in its deduction? Would there be any story left to tell when the reader had all the facts? I believed that there would; and, as an experiment to test the justice of my belief, I wrote The Case of Oscar Brodski.”

Freeman used that inverted structure in his stories only occasionally, but he became identified with it. Other mystery authors such as Ngaio Marsh and Anthony Berkeley followed with their versions of the inverted approach, and it was the central conceit of Frederick Knott’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial ‘M’ for Murder. It also appeared regularly in later television detective shows such as Columbo, The Rockford Files, and Luther.

Most of the Dr. Thorndyke novels and short stories are in the public domain and many can be found at Project Gutenberg or in recent reprint editions. If the prickly and arrogant personality of Sherlock Holmes isn’t your style, you might find Dr. Thorndyke a more agreeable reading companion.