The Weekly Reader Children’s Book Club was one of the most successful mail-order book clubs of its kind, holding a place dear to the hearts of countless kids in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. Long before Amazon brought books by mail to the masses, I grew up receiving new, hardcover children’s books every month, courtesy of the Weekly Reader.

What made the Weekly Reader Book Club special and where is it today?

The start of a competitive rivalry

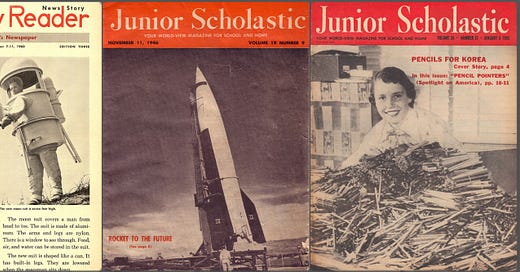

Its story began about a hundred years ago in the 1920s when two rival children’s newspapers began publication—Scholastic News (and Junior Scholastic for younger ages) and My Weekly Reader (later shortened to Weekly Reader). They were small, weekly news magazines published, respectively, by Scholastic Corporation and American Education Press and distributed widely in schools throughout the U.S. They typically were only a few pages long and contained informative articles about science, geography, current events and other educational content.

[My school district subscribed to Scholastic, and I fondly remember looking forward to each edition of Junior Scholastic when I was in elementary school in the 1970s.]

By the 1950s, Weekly Reader and Scholastic had expanded beyond news magazines and launched commercial book clubs aimed at children.

Starkly different business models

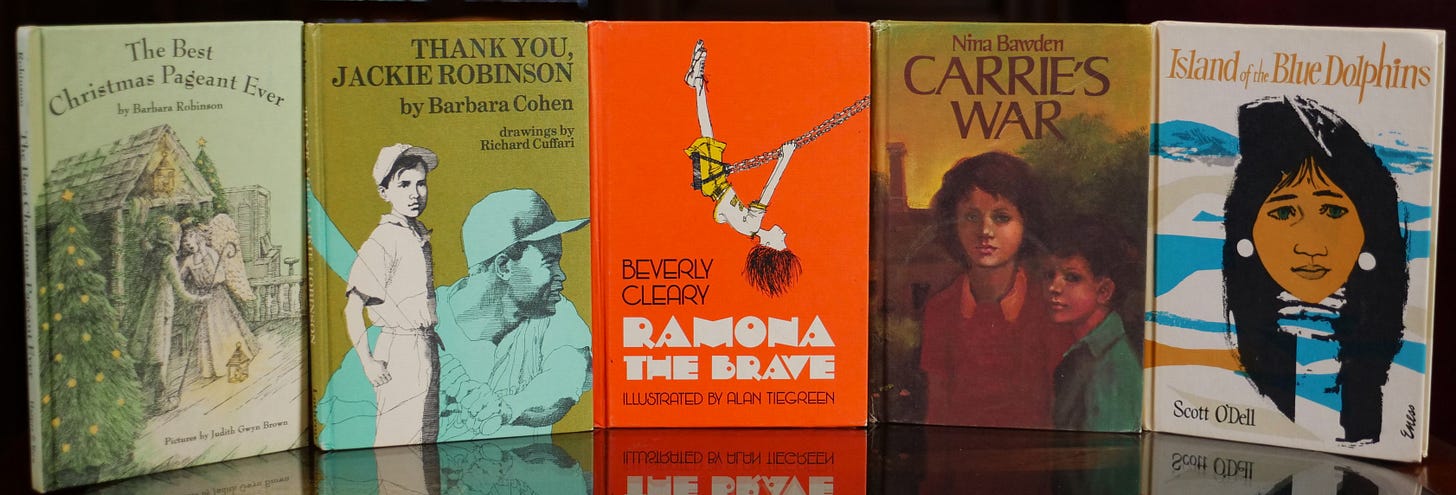

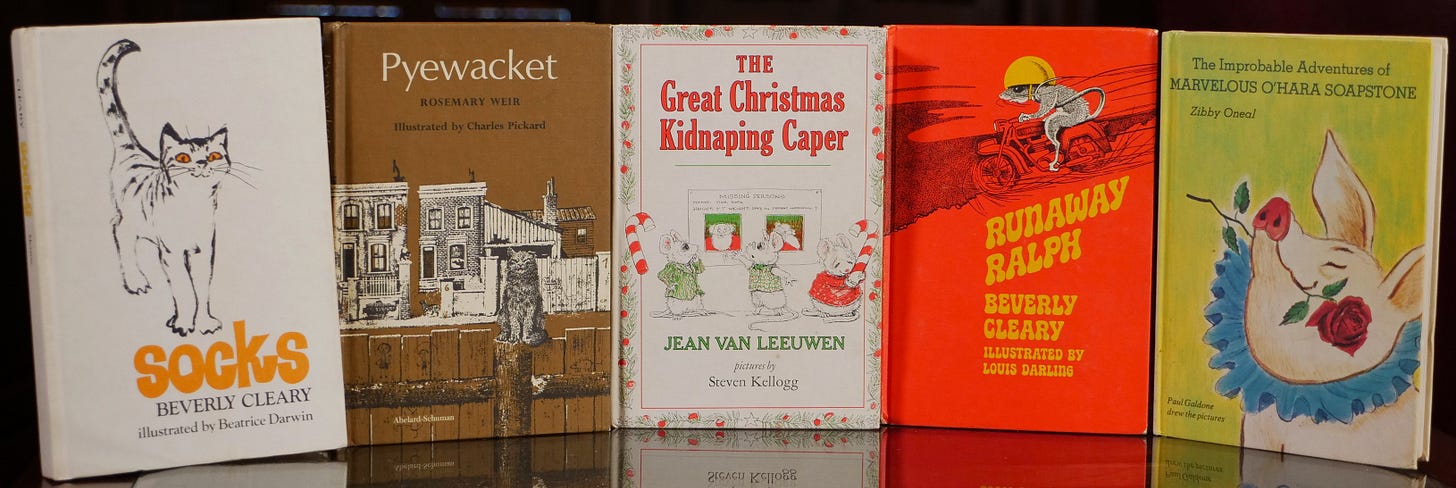

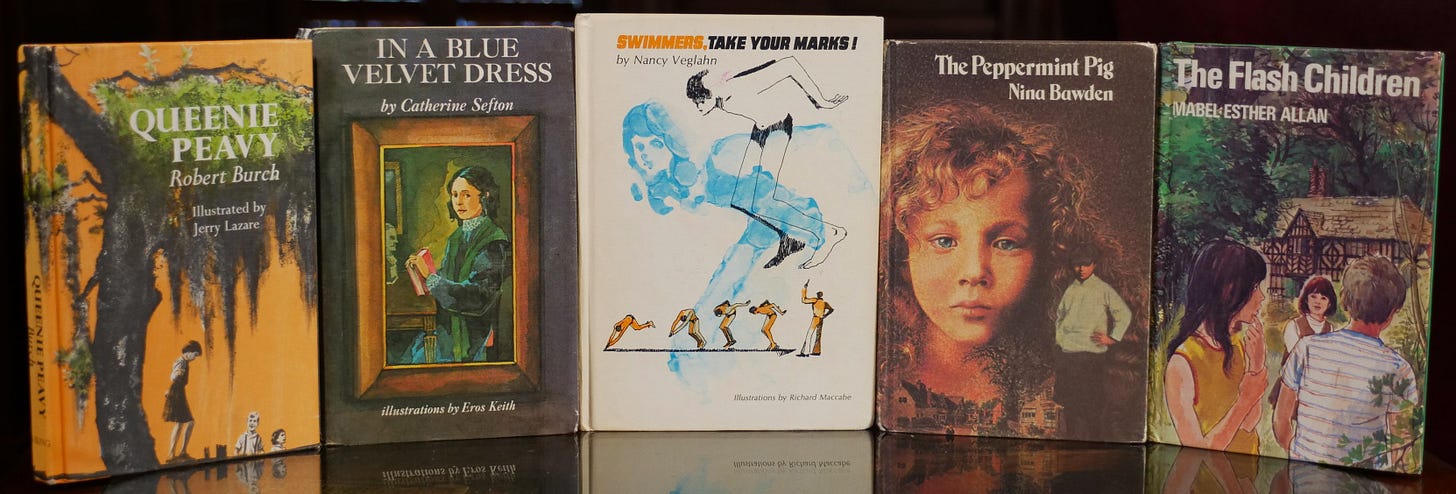

The Weekly Reader Book Club patterned itself after the adult-focused Book of the Month Club, adopting a subscription model that invited parents to place a standing order every month for two or three children’s books selected by Weekly Reader at prices deeply discounted from what retail bookstores charged.

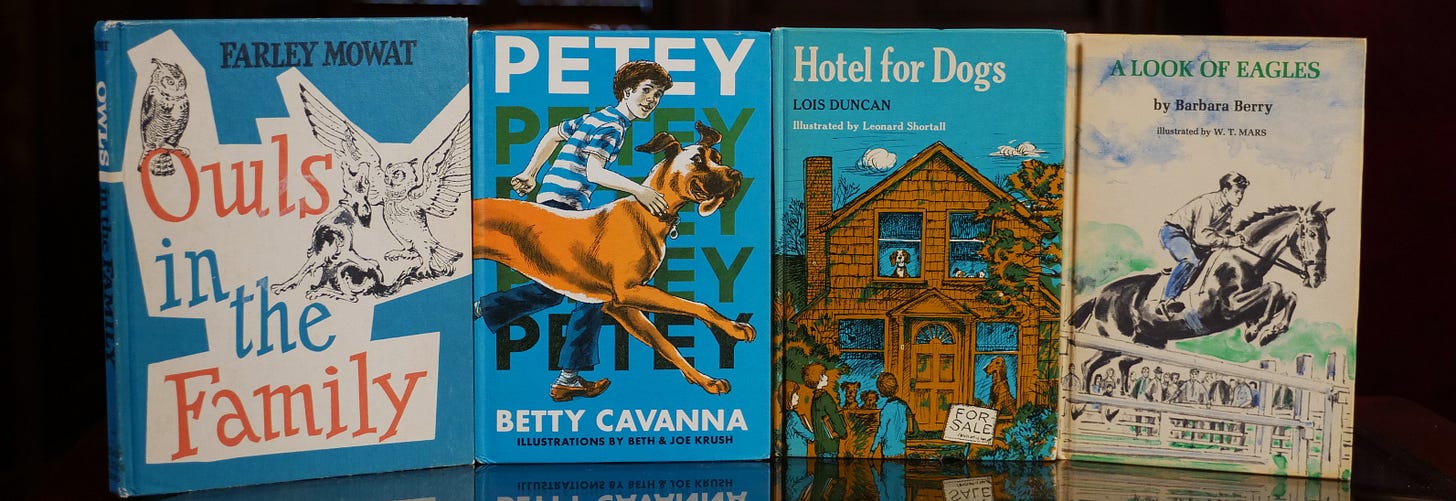

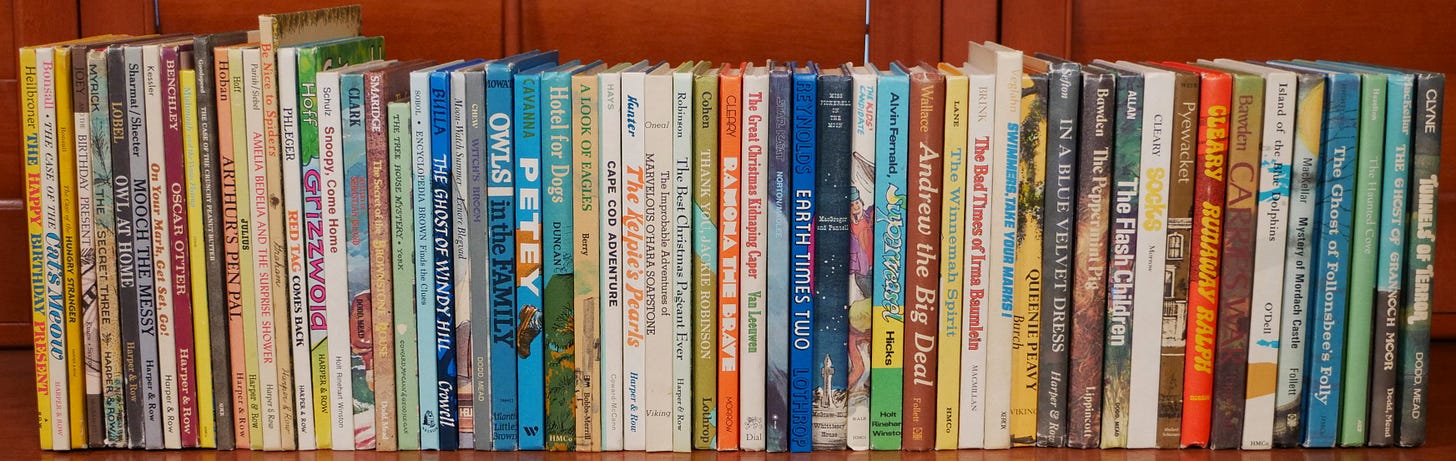

The book selections were carefully curated by staff for quality and reader age. Parents could feel comfortable their kids were reading ‘good’ books, and young readers received a wider exposure to many authors they likely would have skipped over when browsing the shelves of their school or public libraries.

The books were shipped directly to subscribers’ homes, and if they didn’t like the books chosen for them, they could always send them back. [To my knowledge, my parents never returned any books. My siblings and I typically enjoyed everything we received.]

Scholastic took a different approach by opting to sell its books primarily through schools. It distributed catalogs periodically to classrooms and had teachers compile orders, collect payment and then distribute the books to the students. Scholastic’s book club was able to keep its shipping and other distribution costs low by consolidating orders at the school and classroom level, and it continues to operate that way today.

The two clubs also differed in the quality of the books they offered.

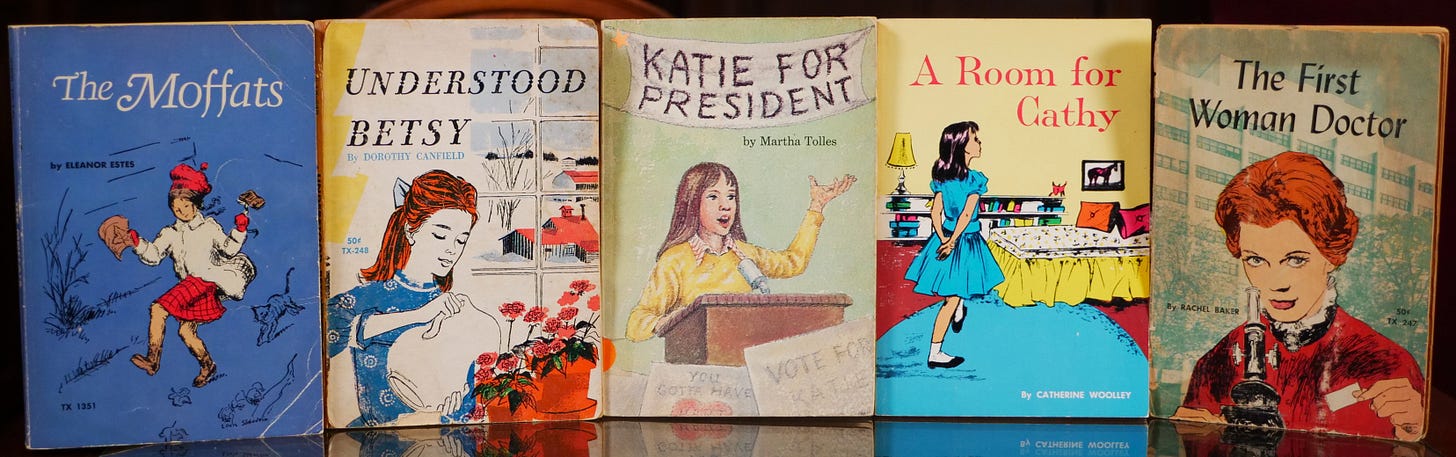

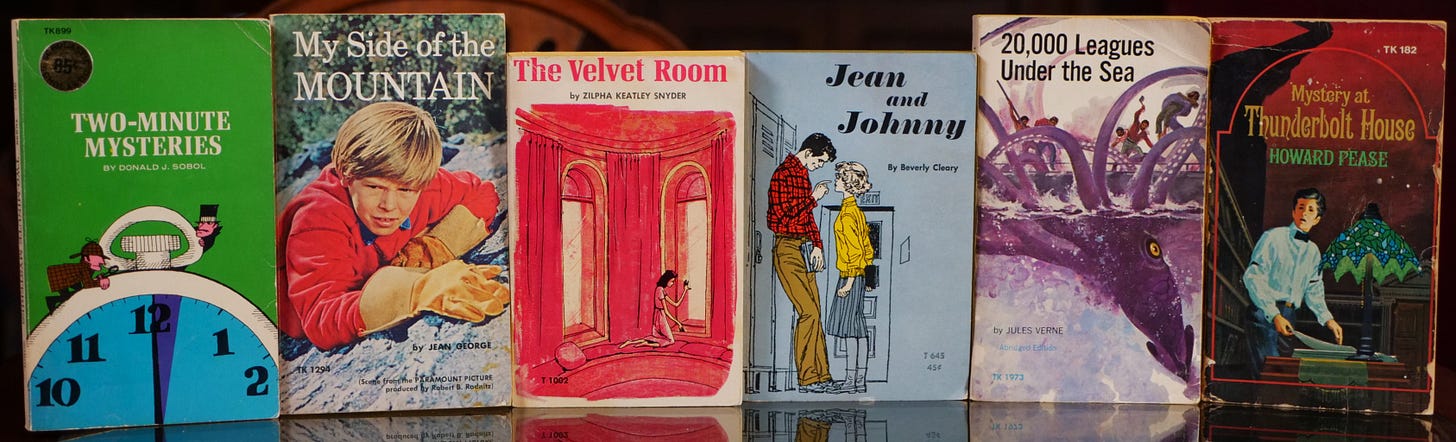

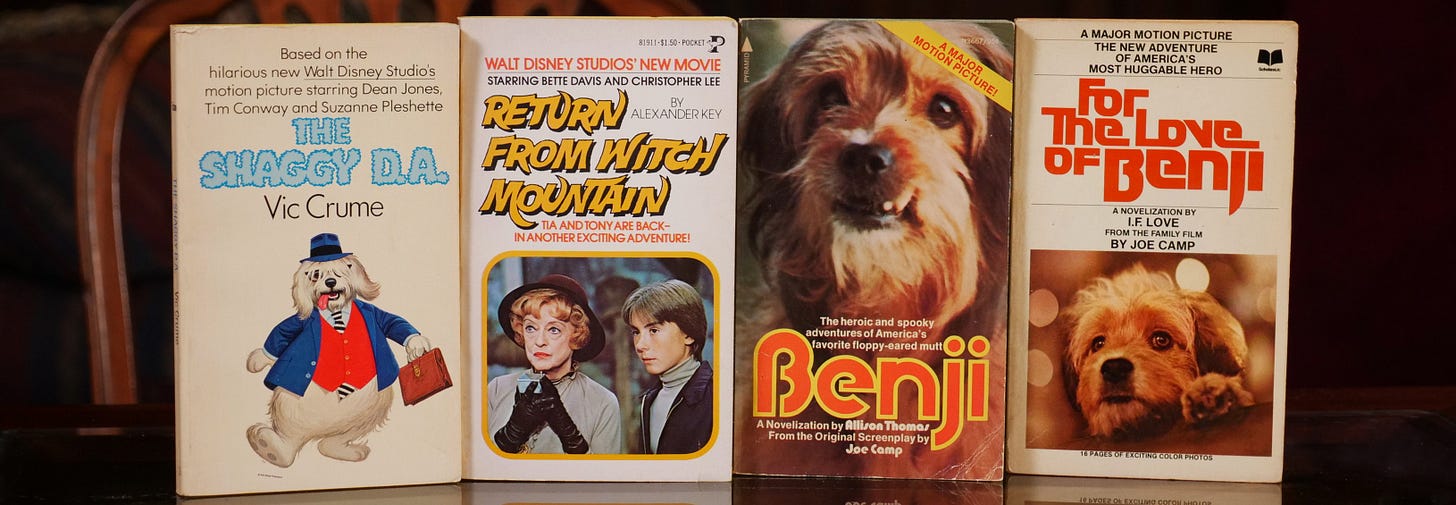

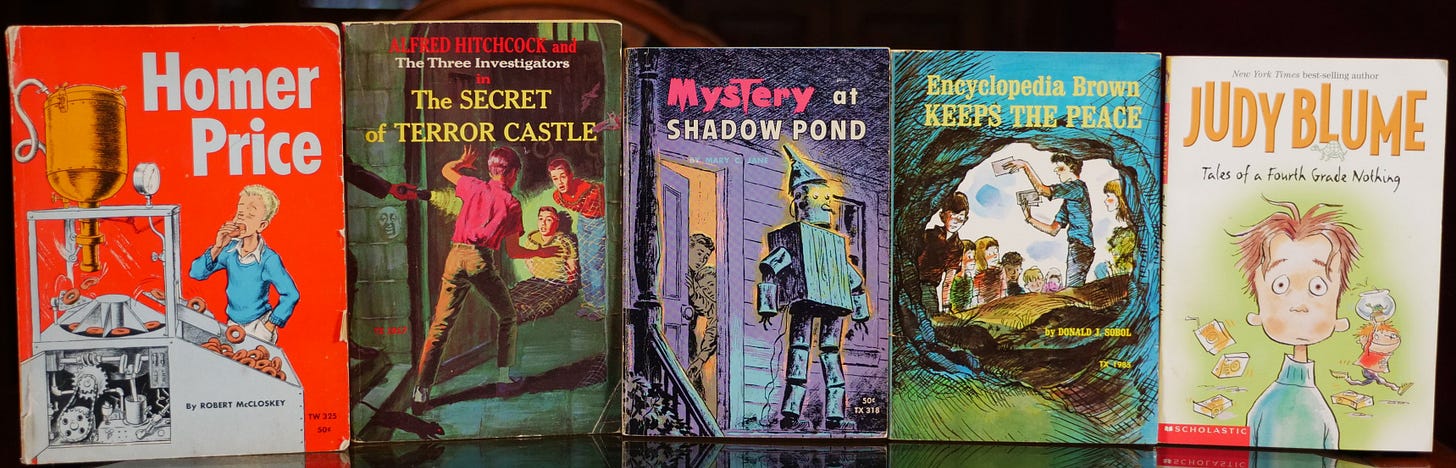

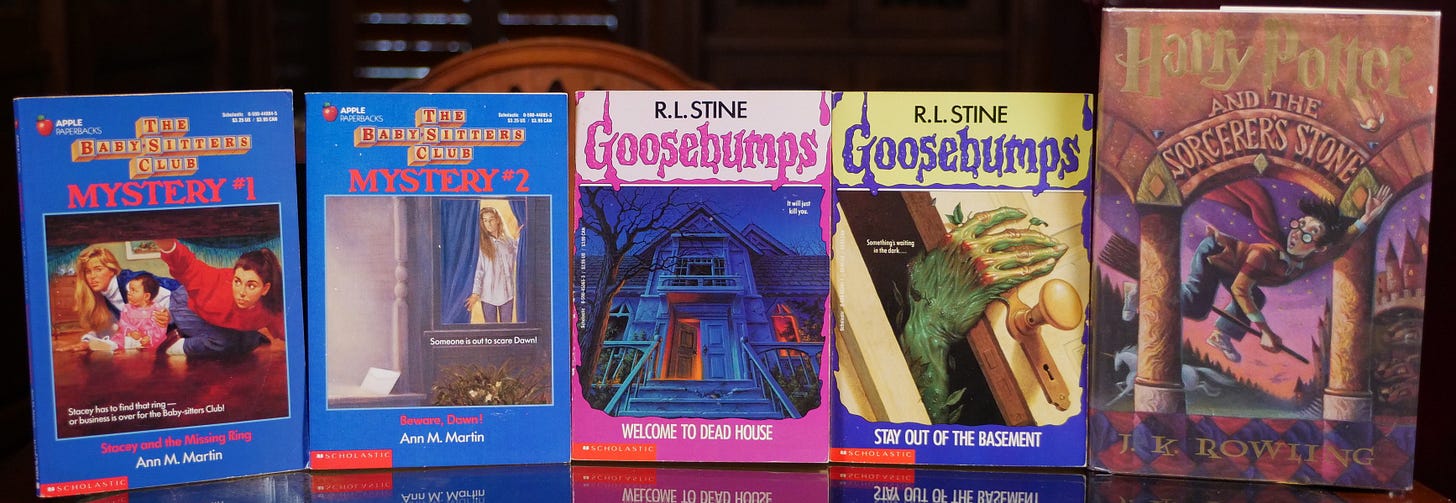

Scholastic partnered with pioneering paperback book publisher Pocket Books to offer cheaply made paperbacks that weren’t meant to last. They were printed on newsprint paper that turned brown and brittle over time, and the glue used to bind the pages together tended to deteriorate as well.

They were extremely affordable, though— often costing 50 cents or less. Scholastic’s selection of titles also included a wide range of pop culture tie-ins, such as movie and TV show novelizations and promotional materials, and comparatively fewer books that might be considered children’s literature.

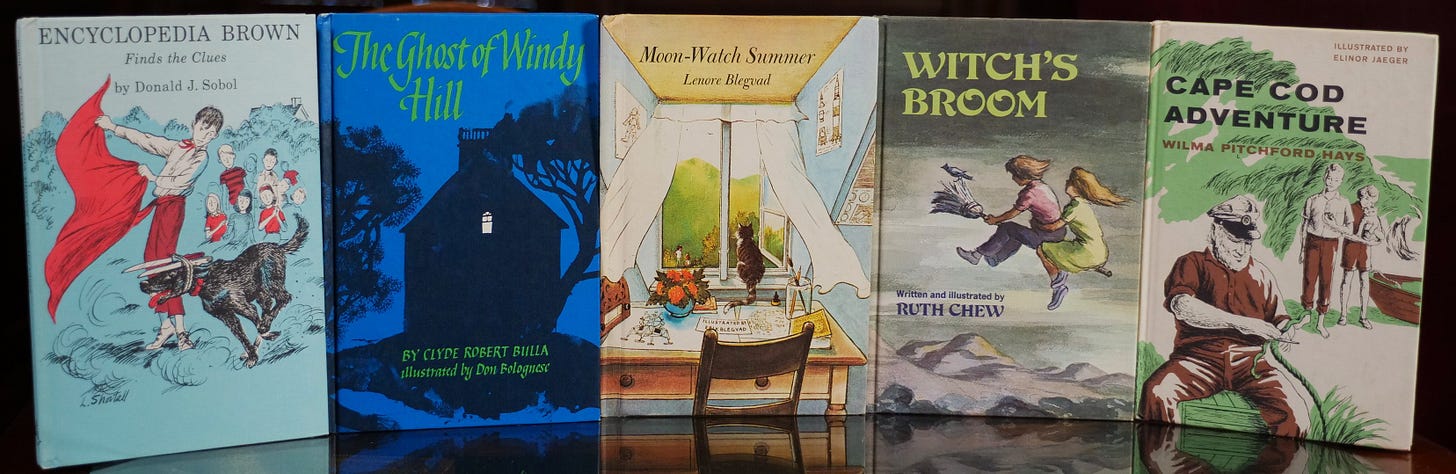

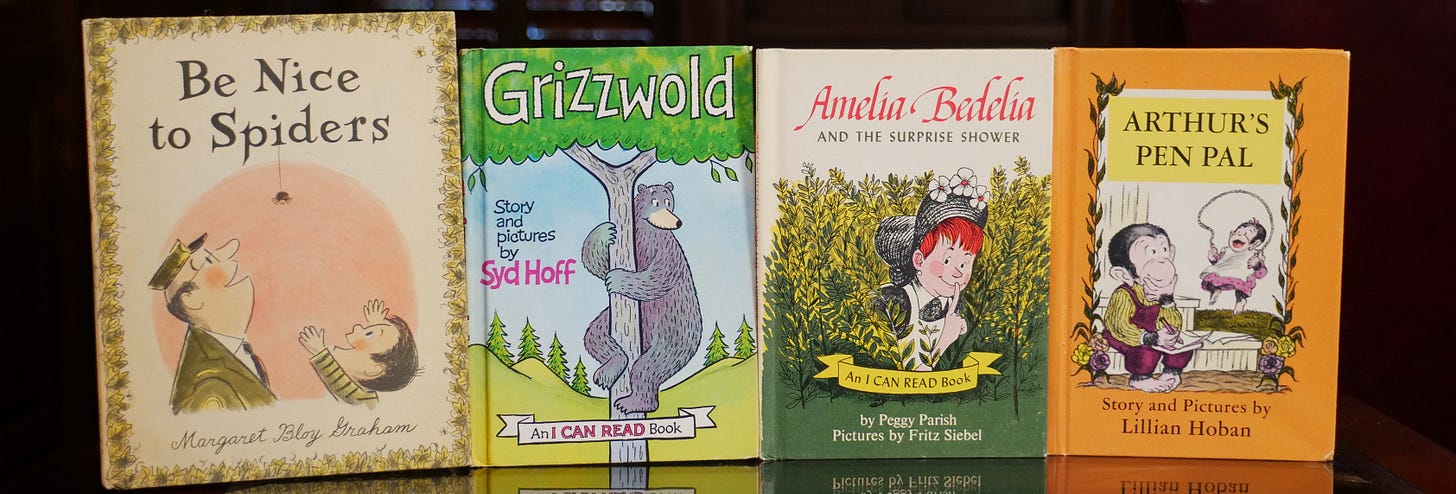

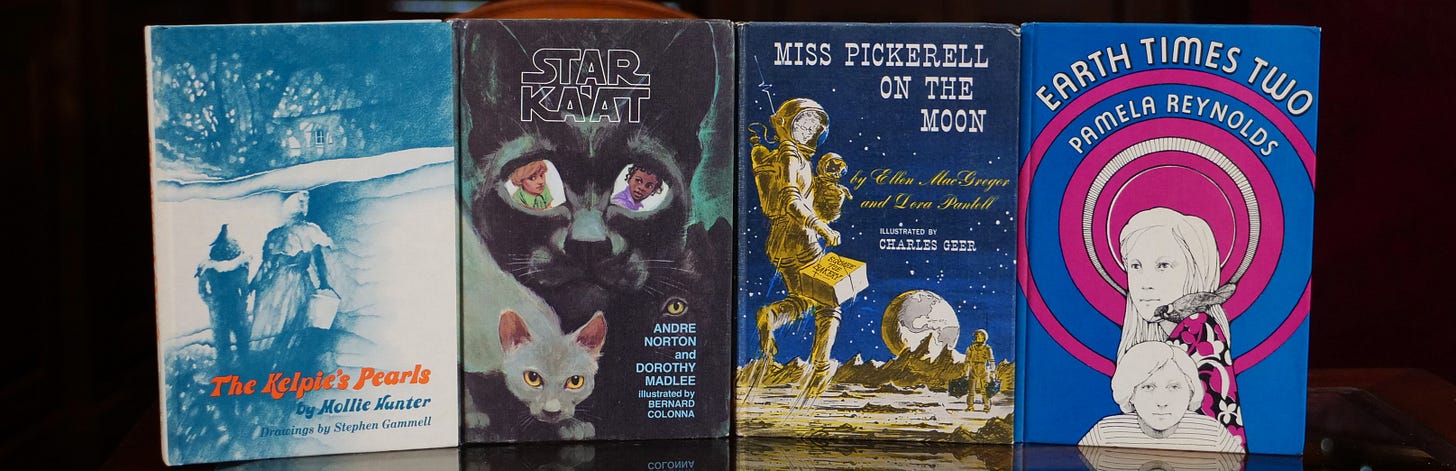

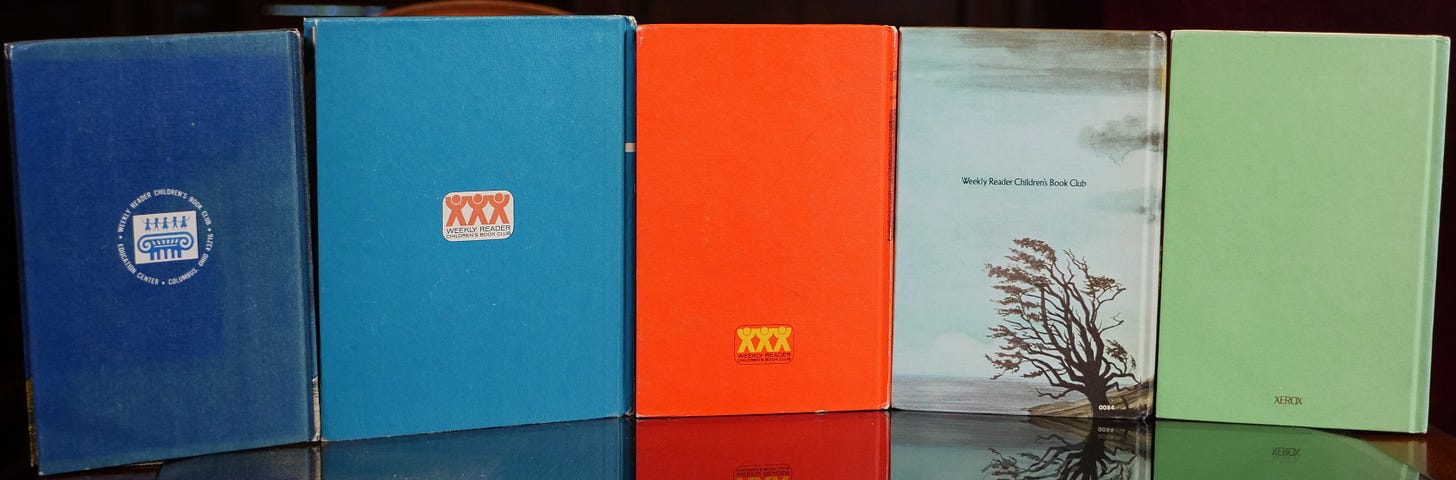

In contrast, the Weekly Reader Book Club prioritized quality over quantity by focusing primarily on well-regarded children’s fiction and publishing them as durable hardcovers, typically with pictorial boards that reproduced the artwork found on the dust jackets of the original publishers’ first editions. After more than fifty years, the hardcover copies I read as a kid still have tight bindings, smooth and creamy white pages, and covers that retain their original color and detail.

A Weekly Reader book typically was two or three times the price of a Scholastic one, and shipping cost more as well, but readers received a higher quality book and for a price well below that of hardcover editions sold in bookstores.

A changing market environment

By the 1980s, though, the competitive environment had changed. Scholastic’s low-cost, high-volume business model that relied on uncompensated school teachers to perform much of the marketing and distribution functions was still going strong.

Scholastic also diversified into other media in the 1980s, forming an audio and video production division, and partnering with film production companies to produce educational videos and television adaptations of books. Revenue from those business lines helped Scholastic pivot to become a more traditional publisher of children’s books, building on the success of series such as The Baby-Sitters Club, Goosebumps, Clifford the Big Red Dog, and a few years later, Harry Potter.

Weekly Reader, on the other hand, stuck with its traditional mail-order subscription model and struggled to sustain it. Rising production and home delivery costs for Weekly Reader’s hardcover books forced it to raise subscription prices substantially in the 1980s and ‘90s, further widening Scholastic’s sizeable price advantage.

Amazon’s arrival in the late 1990s hastened the book club’s demise, as it couldn’t compete with the discounted prices Amazon offered for regular hardcover editions of the same children’s book titles Weekly Reader published. Weekly Reader’s price and convenience advantage over traditional brick-and-mortar bookstores was no match for Amazon’s scale and efficiency.

Two rivals become one

During the book club’s heyday in the 1960s and 70s, Weekly Reader Publishing was owned first by Wesleyan University Press, followed by the Xerox Corporation. Later, during its slow decline, the company was purchased by the R.J. Reynolds Corporation (the tobacco company) and then by The Reader’s Digest Association, neither of which was willing to invest the resources needed to make Weekly Reader competitive again.

After its book club folded, Weekly Reader—the company and the children’s news magazine it had published since the 1920s—continued to limp along until 2012, when Scholastic, by then the largest publisher of children’s books in the world, acquired what remained of its former rival. Some of Weekly Reader’s operations were merged with Scholastic’s, but most of it was simply shuttered.

I miss the Weekly Reader Book Club

I certainly appreciate the many things Scholastic has done over the years to promote children’s books and reading, but I wish there were an equivalent to the Weekly Reader Book Club available to families today that would provide them with high quality and durable books at deeply discounted prices.

Yes, there are subscription-based book sellers today. Large publishers such as HarperCollins and retailers such as Amazon offer subscription book boxes for kids, but the books tend to be flimsy paperback editions. Other, smaller companies such as Bookroo offer monthly boxes of higher quality hardcover children’s books, but their selections are more limited than what Weekly Reader used to provide.

Is there room in the market today for a book club like the Weekly Reader’s? Is there a financially sustainable business model for it?

I don’t know, but I hope there is.

What do you think about this? Do you have fond memories of the Weekly Reader Book Club?

Let me know in the comments below.

I just discovered you because I was looking for more info on the Weekly Reader Book Club. It was one of my primary introductions to books as a child and, as I’ve been revisiting my old favorites recently, I had the same question you pose in your subtitle. I think I may even have to credit those books for my career. Thank you for this post. I, too, wish it were still around.

Thanks and welcome aboard! Children's books led me (indirectly) to create this Substack. I'm a lifelong reader and collector of vintage children's books, with more than 3,000 of them on my shelves, most published between 1875 and 1975. While leading a book club for 5th and 6th graders at my kids' school for several years, I was struck by the lack of older books (pre-2000) in the reading lists prepared by the teachers and librarian. They noted (a) the dearth of older books still in print and (b) the difficulty of getting students (typically boys) to read even the modern classics that remain available, let alone the older classics.

That experience motivated me to start a YouTube channel about 3.5 years ago focused on overlooked classics, old and new, that are at risk of being forgotten. I started out discussing children's books, but those videos struggled to find an audience, so my output over the past couple of years has focused on other genres that aren't penalized as much by YT's algorithm. I created this Substack recently to provide another outlet for my thoughts about books (including children's books) that don't fit the YT algorithm's somewhat narrow view of my channel.