What makes a book a classic?

...and how to start reading them

What makes a book a classic?

Is it the age of a book, and if so, how old does it have to be before it’s deemed a classic?

Is it a function of how widely read a book is?

Does a book's popularity determine whether it becomes a classic?

Is it based on how influential or groundbreaking a book is when compared to its peers and to books published after it?

Does it depend on subjective criteria and evaluations of the quality of its prose or its thematic sophistication and emotional depth, all of which might be lumped under the heading of "literary merit?"

While each of those dimensions might play a limited role in defining what makes a book a classic, I'd argue that the primary determinant is the impact a book has on its readers.

A book that resonates with readers, that inspires them, that challenges them, that thoroughly entertains them, or that broadens their understanding of the world and the people in it — that's a book with the potential to be a classic.

Those kinds of books are more likely to stay in print longer.

They're more likely to benefit from the positive reviews and word of mouth recommendations that often propel a book's popularity.

They're more likely to inspire other authors to pattern their writing after them in an attempt to achieve the same kinds of success.

And very often (but not always) they're crafted with a degree of care, attention to detail, and stylistic flair that elevate the writing above the usual or the ordinary.

No age or literary merit required

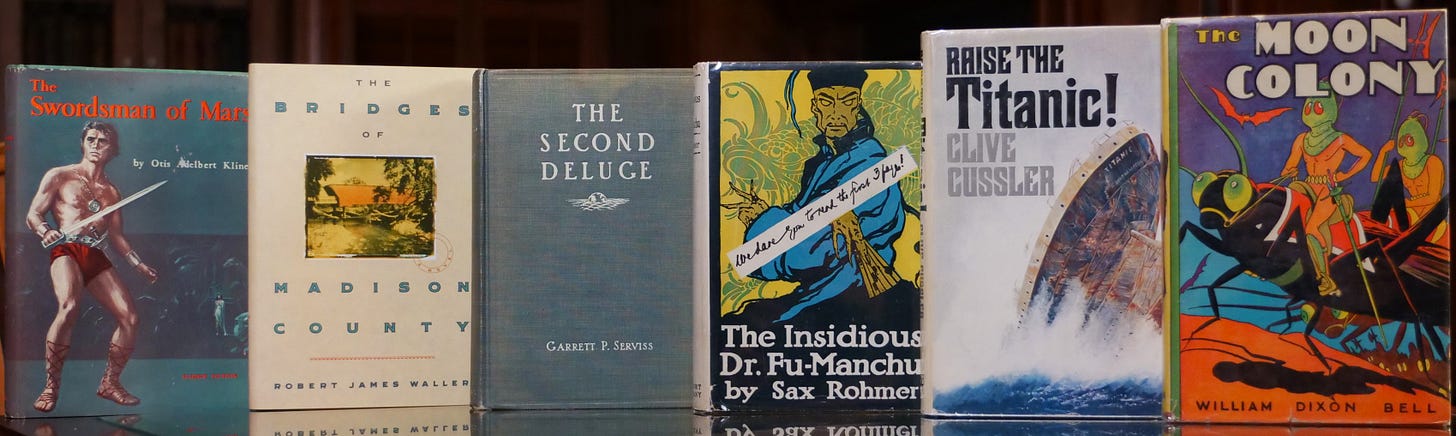

As I said earlier, a book doesn't have to be old to be a classic, and an old book isn't automatically a classic. I believe there are many modern classics that have left a lasting impact, just as there are many older works of little consequence that aren’t classics.

Likewise, classic books aren't always good books, particularly if they helped shape specific genres and the authors who followed in their footsteps.

They might be the literary equivalents of the low-budget gangster movies of the 1930s that led to the genre-defining film noir movement of the 1940s.

Or the early Flash Gordon serials that inspired Star Wars.

Or the cheesy creature features of the 1950s that inspired Ridley Scott's Alien two decades later.

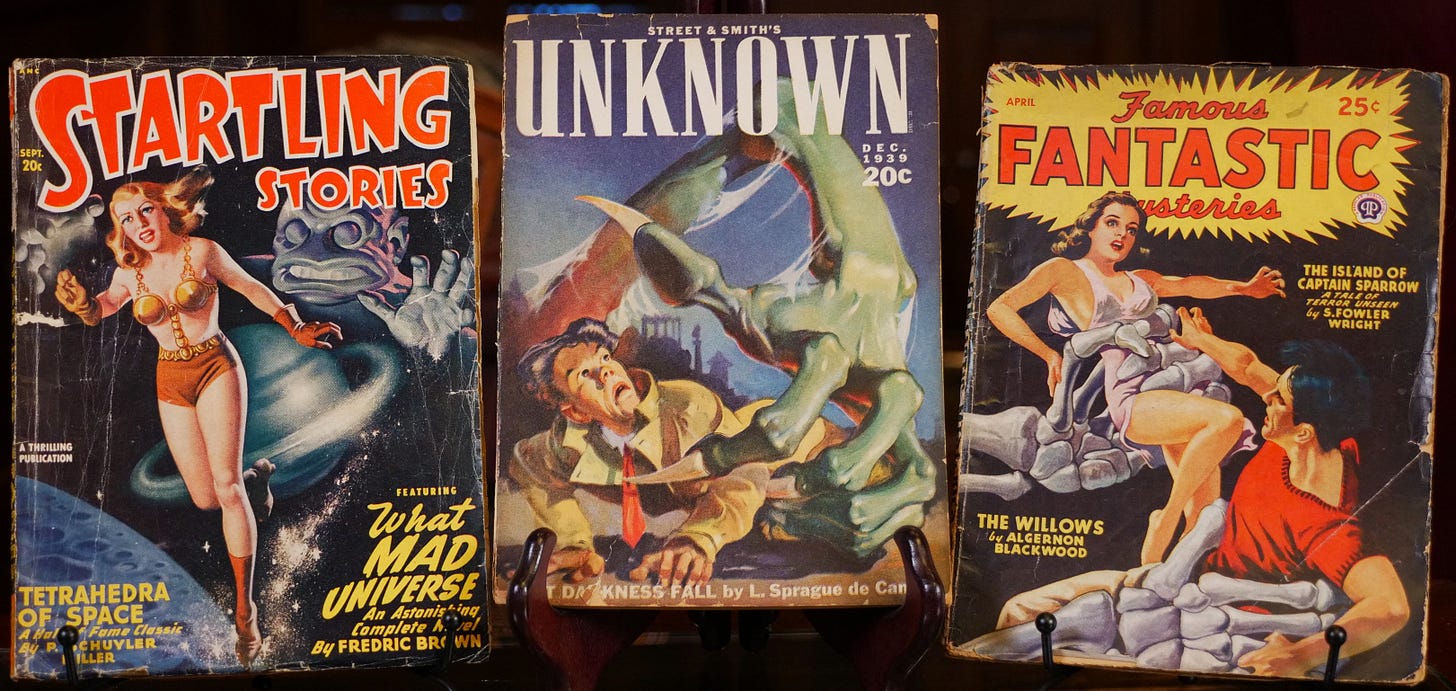

Nineteenth century ‘penny dreadfuls’ and dime novels, along with the pulp magazines of the first half of the 20th century, provide good examples. Where would modern horror, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, thrillers and historical fiction be today without those early pulpy entrepreneurs charting the course?

And many of the chapter book series for children that were mass produced during the early 20th century by the Stratemeyer Syndicate and publishers such as A.L. Burt, Cupples & Leon, and Saalfield can be considered classics for the same reasons.

Am I saying the stories in those early pulps and children's book series were all bad?

Not at all. Their quality varied widely. Some were trite and slapdash, but others were highly innovative and sometimes sublime, and collectively they had a profound influence on readers and on their demand for more and better works of those kinds.

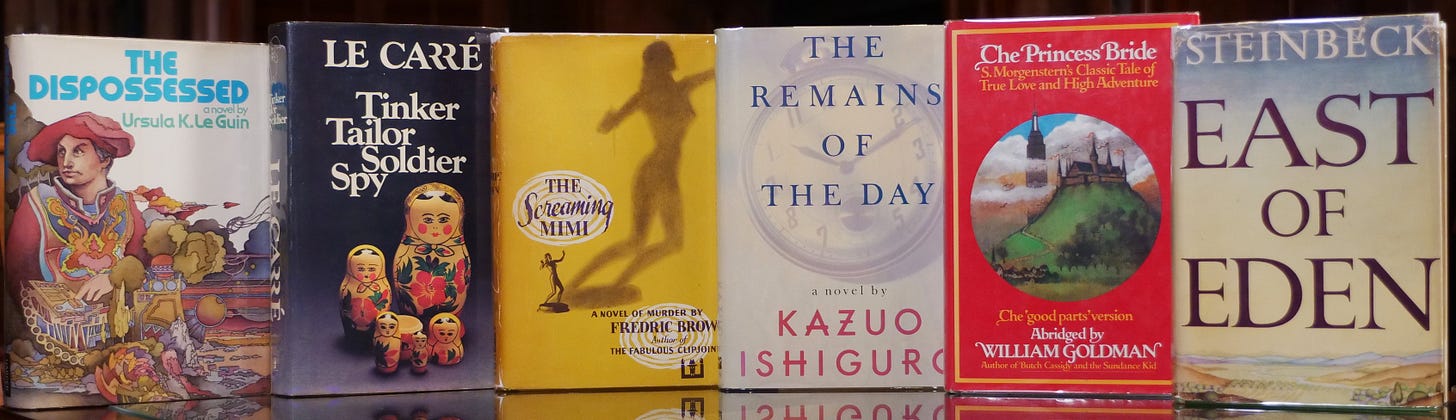

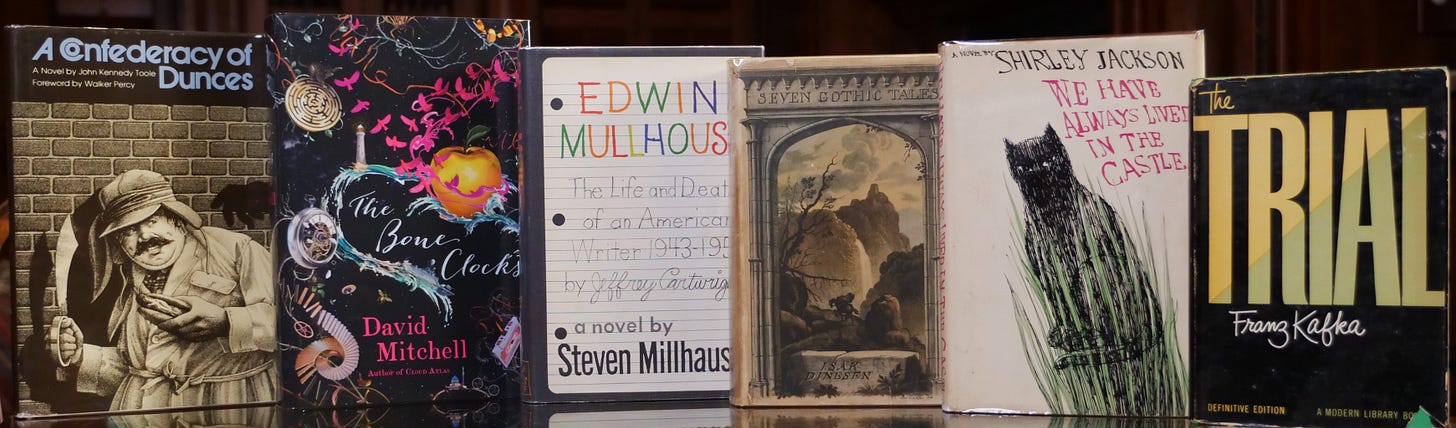

To me, that elevates them to classic status. Those are the kinds of books I like to collect and to talk about—books that have had a lasting impact on readers or, in the case of more recent works, have the potential to do so.

Reading older, literary classics

Reading "the classics" doesn't have to be intimidating, and it doesn't just mean reading tomes from the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries full of archaic and verbose writing. While the works of Dickens, Faulkner, Hawthorne, Joyce, Eliot, Hardy, and the Brontes certainly qualify as classics, they represent only a small corner of a much broader range of classic fiction available to be (re)discovered by readers.

If you want to gain exposure to those older classics, you might consider taking a different path than I did at first.

When I was fifteen, one of my high school teachers had each student pick a well-known classic novel to read and present to the class. The only requirement was that it had to have been written before 1960. I viewed the assignment as a challenge, so I picked the most intimidating classic book I could think of—Herman Melville's Moby Dick.

Well, that was a mistake. I can't recall ever being as bored by a book as I was while reading Moby Dick as a teenager (although Ethan Frome came close). Despite its daunting reputation, I still expected to find a more rousing adventure story in its pages. After all, it's about a quest to hunt a monstrous whale...right?

Well, what I found instead was a book that devotes much of its bulk to the mundanities of life aboard a whaling ship. I deeply regretted my choice about halfway through, around the time I reached Chapter 59, titled "The Line," which spent several pages simply describing a piece of rope.

Clearly, I wasn't ready to appreciate Melville's genius (and I'm not entirely sure I'm ready today).

Instead, I wish I had treated that high school assignment as a warm-up exercise. I would have been much happier tackling one of the picaresque novels of Robert Louis Stevenson, Baroness Orczy or Rafael Sabatini, or an epic adventure by Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne or Sir Walter Scott.

I wouldn't have been ready for Bleak House, but I would have enjoyed Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities.

To this day, I don't understand the logic of high school curricula that assign works such as The Sound and the Fury, Far from the Madding Crowd, The Portrait of a Lady, and The Scarlet Letter as students' early introductions to classic literature.

I don't mean that as a criticism of those works. Rather, it's simply an observation that I don't think they're very accessible works, particularly for teens who likely don't have the life experience or familiarity with complex, verbose writing styles to appreciate fully the storytelling in the books and in others like them.

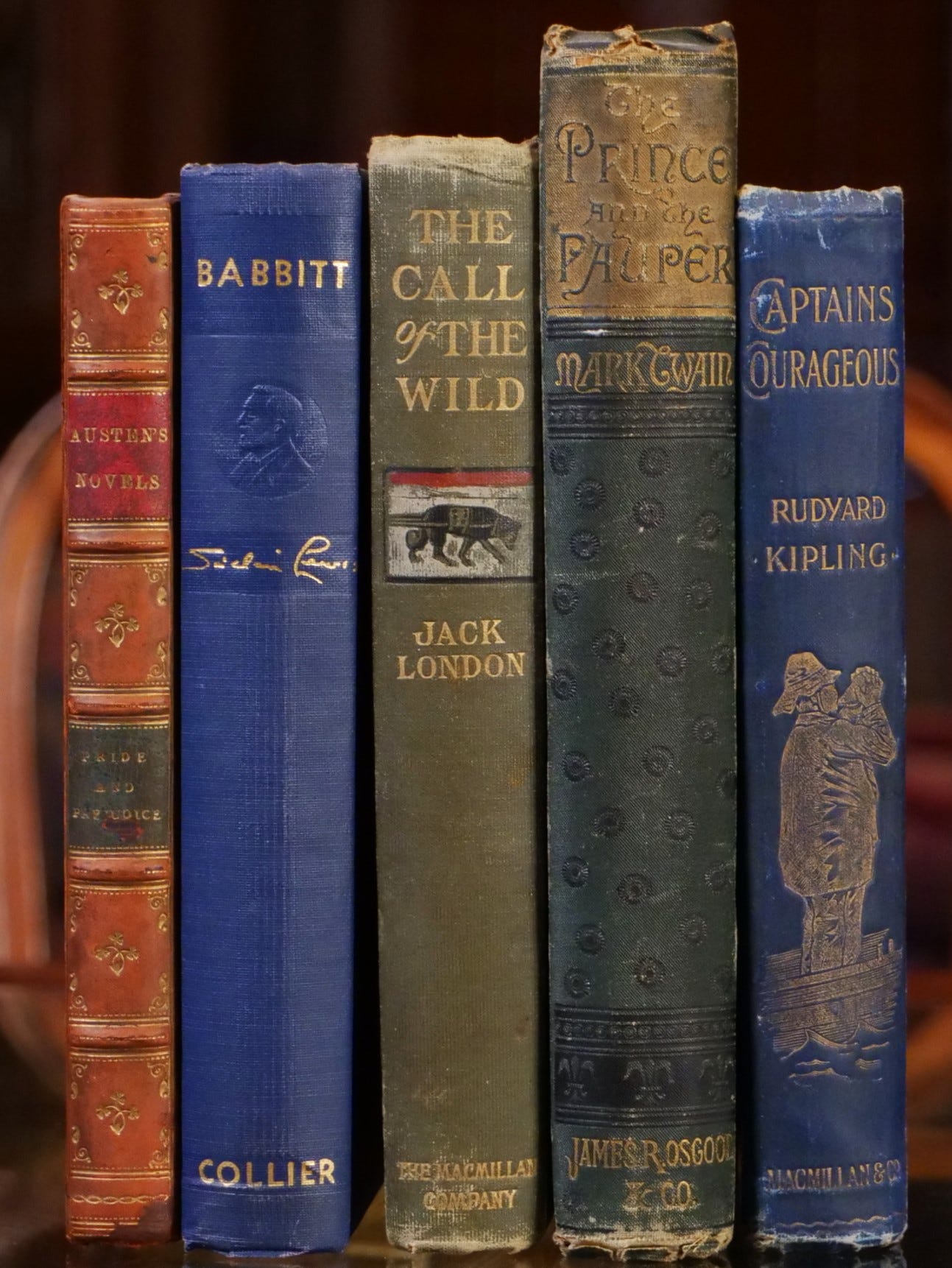

Speaking from my own experience, those kinds of books can take time and acclimation for modern readers to acquire a taste for them. They can be well worth the effort, but it might require some preliminary ventures into less demanding classics to enjoy them as they deserve. The works of Jane Austen, Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, Mark Twain and Kipling, among others, might be better starting points for people of any age seeking to tackle older literary works.

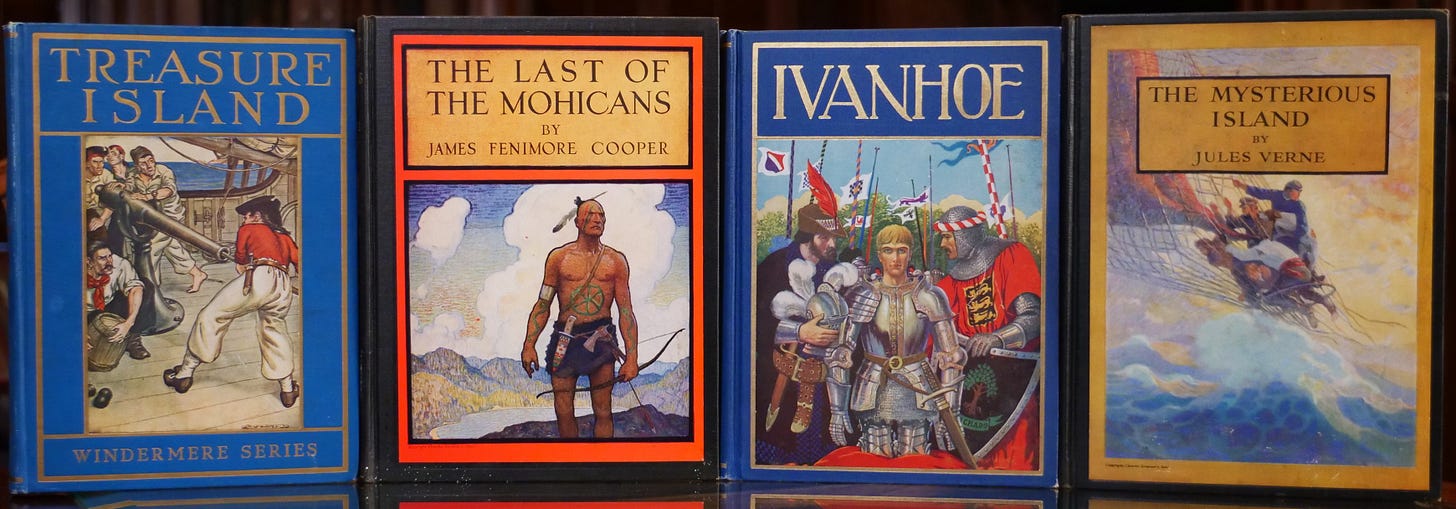

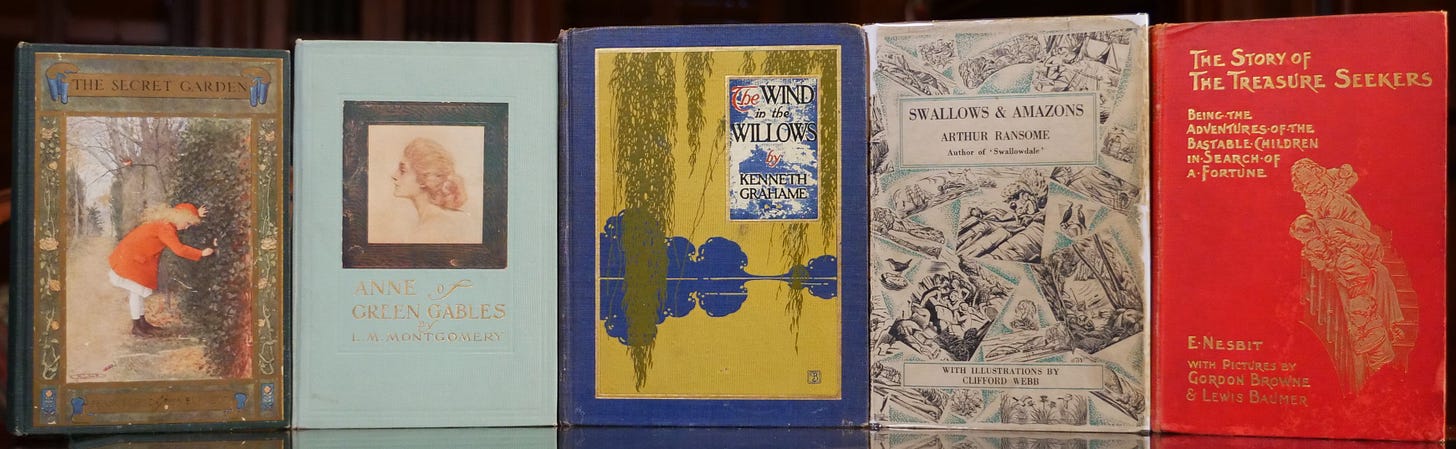

Also, there are the older classics that were either written for children or are thought of today as children's books due to their relatively kid-friendly content or their earlier film, television and book adaptations for kids. Examples include Treasure Island, The Secret Garden, Anne of Green Gables, The Last of the Mohicans, The Wind in the Willows, Ivanhoe, The Mysterious Island, Swallows and Amazons, and The Story of the Treasure Seekers.

These are great entry points to older, classic literature for anyone, and especially for children, who might otherwise never be exposed to the influential works of the past that have shaped the fiction genres and popular culture of today.