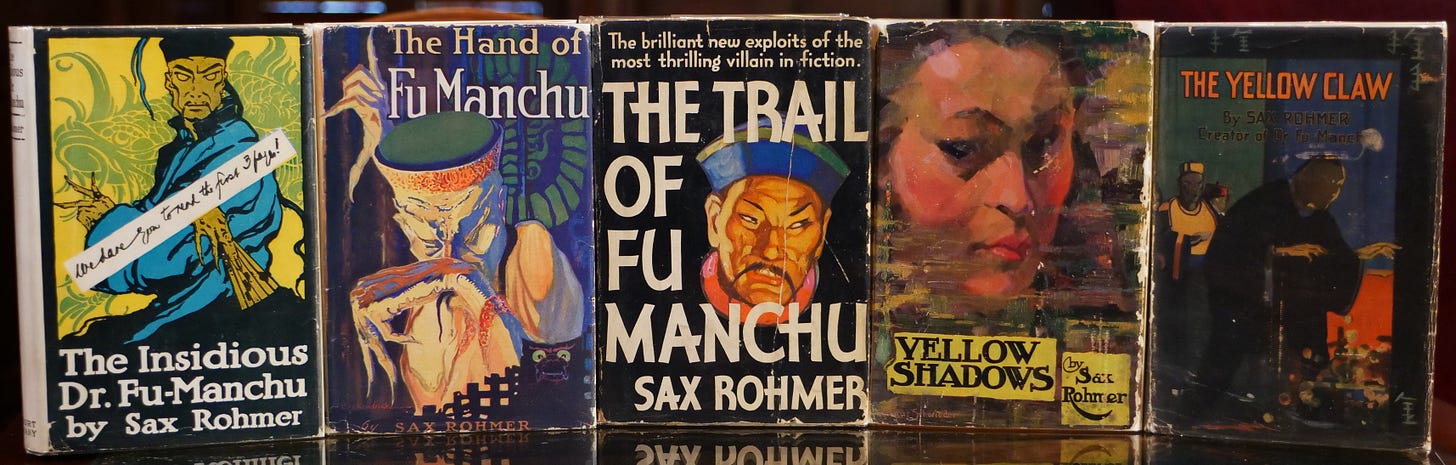

Asian and Asian-inspired works of fiction have experienced a renaissance in the English-speaking world in recent years as readers have discovered new literary and cultural frontiers to explore. I’d like to highlight a few classics worthy of rediscovery written by Western authors who penned works inspired by Chinese history, literature and mythology at a time when 'Yellow Peril' scaremongering was common in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Their works helped to inoculate readers against the fear and prejudice of that movement and to foster greater interest in the West's engagement with China over the past century.

Western literature has long been fascinated by Asian cultures and traditions, often showing respect and appreciation for the artistic beauty, time-honored traditions and philosophical worldviews to be found in that part of the world.

The attention hasn’t always been positive, though, as many western writers throughout history have accentuated and fetishized the exotic otherness of the East and, in some eras, even demonized and propagandized the insidious Asian threat they imagined confronting European-rooted societies.

Here I discuss a handful of overlooked classics of the more positive variety inspired by Chinese history, literature and traditions. Some are over a hundred years old, while others date back just a few decades.

They’re respectful works by Western authors that variously celebrate the spirit of the Chinese people, pay homage to Chinese literary pioneers, and emulate some of the more fantastical elements of the Chinese storytelling tradition. Each deserves more attention today.

Rural Peasant Striving

In 1931, an American Presbyterian missionary in rural China published a book that would become the top-selling novel in the US for two consecutive years. Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth is a work of historical literary fiction that’s the first volume in her House of Earth trilogy that follows several generations of a peasant family in rural eastern China.

The Good Earth begins just before the turn of the 20th century and focuses on Wang Lung, a farmer with a small plot of land on which he grows rice to support himself and his father. He’s a simple man, industrious, illiterate and in need of a wife—one he believes should be hardworking and unattractive enough to live with him without complaint in his tiny, earthen-walled hut. Using his meager savings from the proceeds of his farm, he buys a wife, named O-Lan, from a wealthy landowner who had employed her as a kitchen slave, and together they start a family.

The rest of the novel follows Wang Lung over the years as he, O-Lan, and their children weather the vicissitudes of life—including famine, floods, bandits, revolutionaries . . . and temptation. It’s a parable that celebrates the virtues of work ethic, thriftiness and modesty as a path to success; but at the same time, it shows how following that path can end up eroding the virtues and values that paved it.

The more Wang Lung achieves, the more wealth he acquires, and the more social stature he attains, the farther away from the soil he gets, symbolizing his loss of moral grounding. Hence the novel’s title.

Although the plot centers around Wang Lung and his efforts to build a better life for his family, the emotional and ethical core of the story resides in O-Lan, his wife. Hers is the voice of reason, of prudence, of wisdom; and her selfless sacrifices and abnegation for the benefit of her family are inspiring and heartbreaking.

Published during the depths of the Great Depression, The Good Earth struck a chord with readers around the world that was echoed a few years later with the publication of John Steinbeck’s similarly-themed The Grapes of Wrath in 1939.

Both novels present deeply sympathetic looks at the plight of poor farmers who face many obstacles—from bad luck, to bad weather, to bad faith business associates, and the vagaries of government decisions—as they try to support their families and escape their hardscrabble circumstances.

Both novels won the Pulitzer Prize, and Buck and Steinbeck each won the Nobel Prize for Literature in large part due to the impact The Good Earth and The Grapes of Wrath had on the public’s consciousness around the world. Steinbeck’s novel is more overtly political, while Buck’s has a more humanistic feel to it.

Also, unlike Steinbeck, who had very little first-hand knowledge of the Okie situation when he wrote The Grapes of Wrath, and was later accused of exaggerating and sensationalizing the plight of the Joad family and others like them in his novel, Pearl Buck knew rural China extremely well.

She was born in West Virginia, but her missionary parents brought her to China when she was an infant, and she spent 34 years there, much of it in rural villages like the one depicted in The Good Earth, before publishing the novel at the age of 39.

She spoke fluent Chinese, having learned it alongside the Chinese children she grew up with, and she understood the many hardships facing peasant folk there—their lack of a social safety net, their vulnerability to exploitation, and the expendability of daughters who might be sold into slavery as domestic servants or as brothel workers to protect their families from penury or starvation.

Her sympathetic portrayal of the lives of ordinary Chinese farmers helped bridge the cultural divide that had fueled anti-Chinese sentiments in the US and Europe for decades. It became an early antidote to the ‘Yellow Peril’ propaganda common in the press, in literature, in films, and in government policies at the time by showing the public an East-West perspective based on common ground rather than difference.

Read this book. It’s considered one of the great American novels, despite the lack of Americans in it.

A Mystery Genre Pioneer

Edgar Allan Poe and Wilkie Collins often are credited with pioneering the mystery genre in the mid-19th century, but that disregards centuries of Chinese literary history in which mystery and detective stories have played prominent roles, often involving fictionalized exploits of legendary crime solvers from China’s distant past.

Perhaps the best-known today of those early detectives is Judge Dee, based on a 7th century historical figure named Di Renjie, who over a lengthy career served as a provincial prefect, as the secretary general of the Chinese supreme court, and as the chancellor to the Chinese empress. The real Judge Dee was renowned in China for his integrity, learnedness and perspicacity, and the fictional version of him shared those qualities.

Outside of China, Judge Dee might have remained unknown but for the efforts of a Dutch diplomat named Robert van Gulik. Born in 1910, Van Gulik spent nine years of his childhood in Indonesia, where he developed a love for Chinese history and studied Mandarin and other languages. Upon finishing school, he joined the Dutch foreign service.

While stationed in China during World War 2, he ran across a lengthy, anonymous 18th century Chinese manuscript recounting several of Judge Dee’s fictional cases. Recognizing its potential interest to western readers of mystery fiction, Van Gulik translated it in his spare time, making minor revisions to streamline the story and to provide basic explanations of things for readers.

He didn’t translate it into Dutch, though. Instead, he translated it into English, in which he was very fluent, because he thought it would reach a larger audience and also simplify later translation into other languages.

Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee was first published by Van Gulik in 1949, and it remains in print today.

In it, Judge Dee is a magistrate judge posted to an outer province of China at an early stage of his career. As a judge, Dee’s official duties differ substantially from those found in the legal traditions of the US and UK. “Due process of law” works differently in the Chinese context, and it can feel a little disconcerting for readers used to western systems of justice.

Here in the US, the investigatory, prosecutorial and adjudicative roles in the legal system are separated and performed, respectively, by the police, by the prosecuting attorney’s office, and by the judge and often a jury. (If you’ve ever watched the intro to the long-running TV show Law & Order, you know what I’m talking about.)

Trials in the US are structured as adversarial proceedings that provide significant privileges and protections to defendants, including opportunities to challenge the work of each of the entities responsible for the different aspects of their prosecution.

In contrast, Chinese magistrates such as Judge Dee were empowered to perform all of those judicial functions themselves. In his stories, Judge Dee is the police, the district attorney, the judge, the jury, and in some cases, the executioner, all rolled into one.

He has almost unlimited authority, and the potential for judicial abuse is enormous. The investigation methods used by Judge Dee violate many of the civil rights enshrined in western legal procedure. Torture is commonly used or threatened to extract information and confessions, and the judge and his assistants tend to trample privacy and property rights, and even engage in occasional legal entrapment, to prove their cases.

Some magistrate judges in that era were corrupted by the formidable power they wielded within their provinces. But Judge Dee was different.

You see, Chinese judges had one very important check on their authority. They had to be correct in their final judgments. There was little tolerance for judicial error. Someone wrongly convicted could appeal their conviction and, if exonerated, see the punishment that was their sentence exacted upon the judge who convicted them. Imposing the death penalty on a convicted murderer could lead to the judge’s own execution if he made a mistake during the investigation or trial.

Unlike some of his peers, Judge Dee takes seriously the threat of personal accountability for his rulings, leading him to be diligent and thorough in his investigations and not rush to judgment.

He’s an entertaining character, too. Like Sherlock Holmes, he’s supremely confident in his powers of observation and in his analytical abilities. He uses creative and unorthodox methods of detection, including hiring as his chief lieutenants a pair of con artist thieves he once convicted and pardoned. And he’s a bit reckless in the risks he takes in pursuit of the truth, given the harsh personal consequences he could face if it turns out he’s wrong.

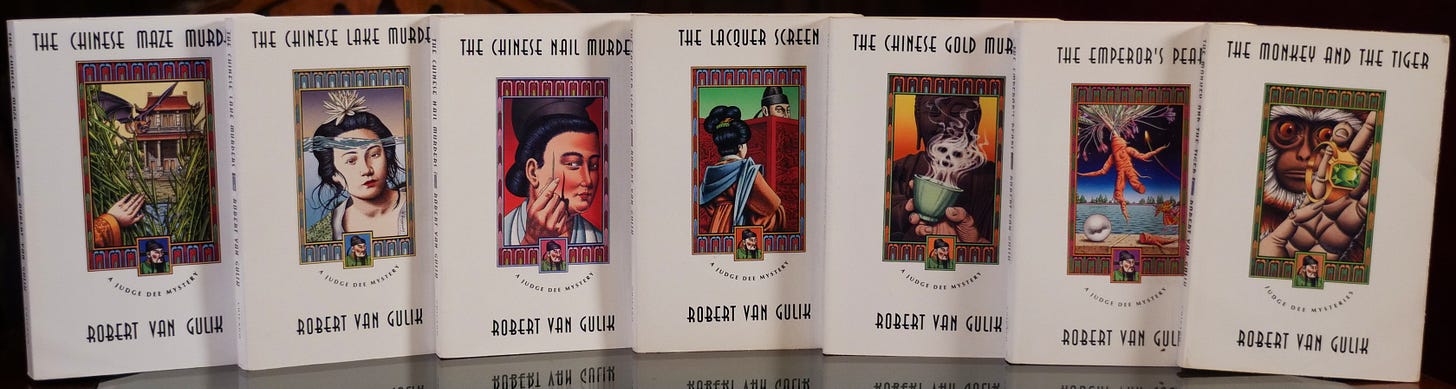

Van Gulik’s translated volume of Judge Dee cases became a sensation upon publication, prompting him to begin writing his own Judge Dee stories. Over the next two decades, he published 16 more volumes of Judge Dee mysteries, many of which were inspired by actual case records from Chinese history centuries earlier.

They’re written in a style similar to the first book, but are a little more accessible to western readers and have stories that conform more closely to many of the conventions of modern mystery fiction.

Structurally, the Judge Dee books resemble procedural crime fiction more than traditional detective fiction, although aspects of both are present. In them, Judge Dee is a multitasker working on several unrelated cases at the same time. Van Gulik’s narrative weaves together the various investigations, which are eventually resolved by the end of each book.

And stylistically, they’re a lot of fun and can be a welcome change of pace from your typical detective fiction. They even have hints of the supernatural in them, mainly involving ghostly visitations, messages and foretellings.

You can read the novels in almost any order, although it probably works best to start with the first book in the series, which introduces the characters. The second book, 1951’s The Chinese Maze Mystery, is actually the 13th book in the series’ internal chronology that spans nearly two decades, and the other books jump around in the timeline too.

Ghostly Inspirations

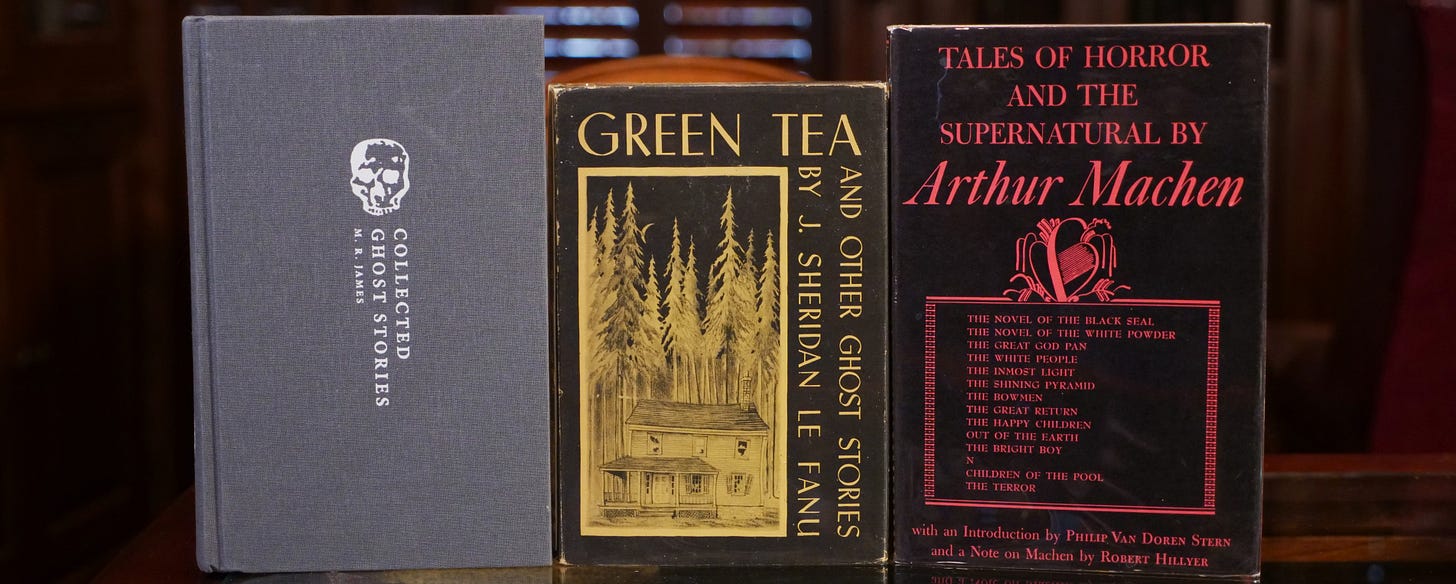

The late 19th century was a kind of Golden Age for tales of the supernatural, as authors such as M.R. James, J. Sheridan Le Fanu, and Arthur Machen gave ghost stories and tales of the occult an air of respectability while establishing many of the tropes and templates used by generations of later authors.

One of the most significant of those ghost story pioneers is also one of the least heralded today.

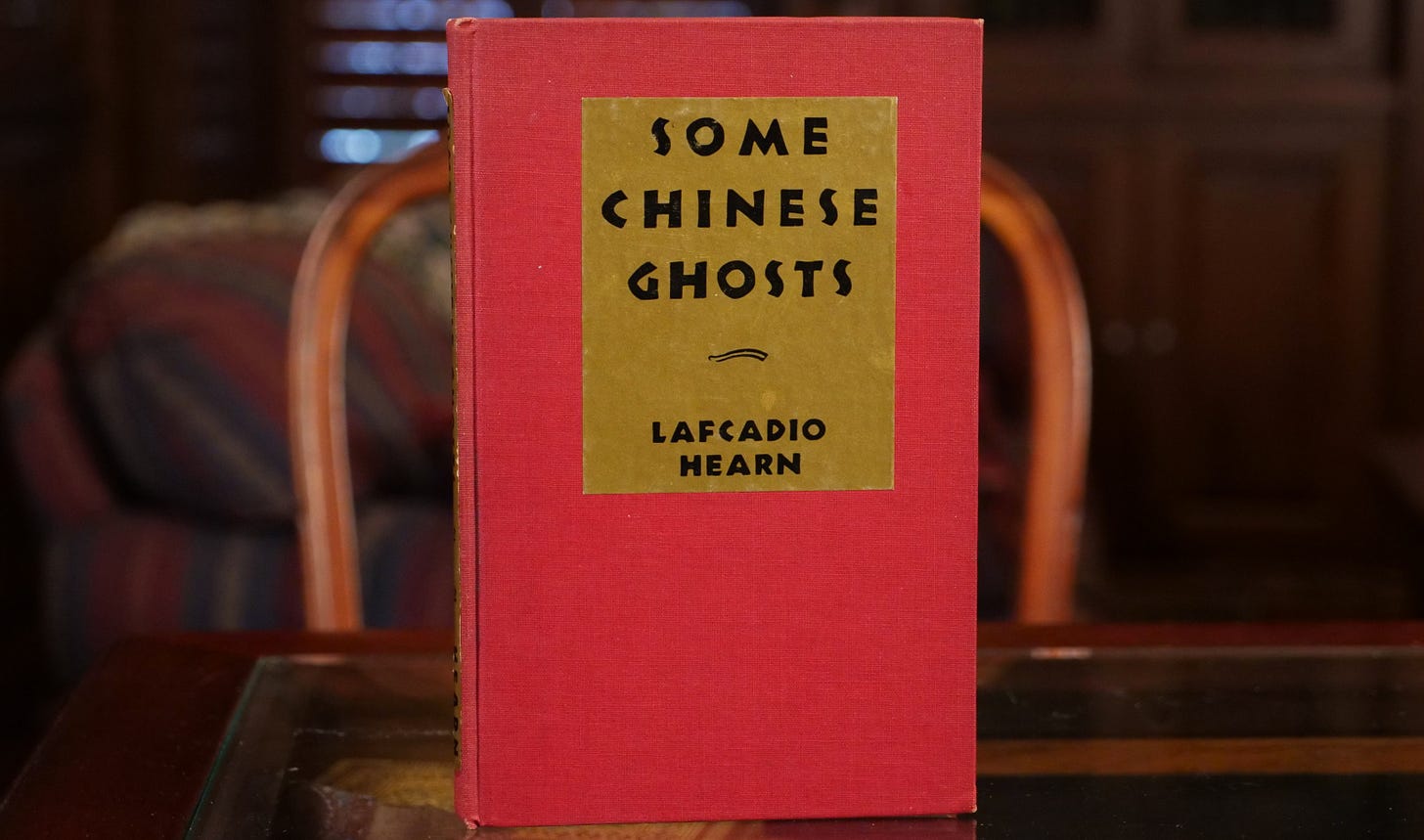

Lafcadio Hearn was a half-British, half-Greek journalist working for a newspaper in New Orleans when he published his first collection of stories in 1887 titled Some Chinese Ghosts. It’s a slim, 53-page volume containing six stories inspired by Chinese folklore that had been translated or adapted for English-speakers only rarely before then.

Although ghosts and other spirit beings figure prominently, the stories might best be described as uncanny or unsettling rather than scary. Hearn was passionate about Asian culture, and he wanted his depictions of Chinese mysticism to intrigue Victorian-era readers, not frighten them.

This debut volume isn’t Hearn’s best work. The stories are a little uneven. Some lack the narrative drive and focused sense of direction one would expect to find in a story only a few pages long. But all of them provide a fascinating glimpse into how Chinese culture was perceived and championed at the time by enthusiasts such as Hearn.

Three years later in 1890, Hearn traveled to Japan and remained there until his death in 1904, where he wrote fiction and nonfiction works about Japanese customs, beliefs and folklore. The folklore-inspired Japanese ghost stories he wrote during that period are among his most famous works. They helped open the eyes of western readers to a new strain of fantastical fiction that provided creative inspiration in later years to genre-stretching authors ranging from Clark Ashton Smith to Jorge Luis Borges.

Hearns’ stories are in the public domain and can be downloaded at Project Gutenberg and Librivox.

The Lazy Bard

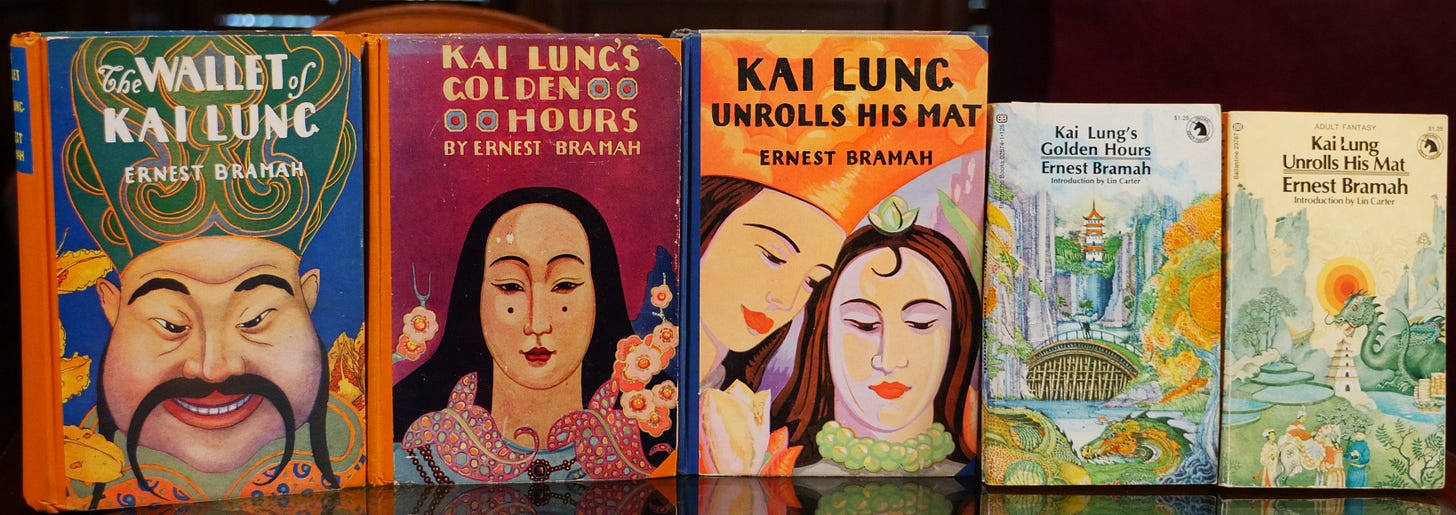

While Lafcadio Hearn was living and writing in Japan, another British author, Ernest Bramah, began composing his own homages to Chinese folklore and mythology—a series of light-hearted books featuring an itinerant tale-spinner named Kai Lung, who claims to have a story for any occasion and is sometimes forced to prove that assertion in order to save his own skin.

The Kai Lung books, starting with The Wallet of Kai Lung in 1900, are novels in name only. In reality, each is more like a fix-up of several loosely connected short stories told by the title character to audiences he meets in a thin framing narrative that, in the first volume, finds him wandering the roads as a hobo, beguiling a variety of scoundrels with his stories along the way.

In another volume, 1922’s Kai Lung’s Golden Hours, he’s imprisoned by a Chinese mandarin and compelled like Scheherazade in the Arabian Nights to entertain the lord with tales he hopes will forestall his impending execution.

And in a third volume, 1928’s Kai Lung Unrolls His Mat, he searches for his kidnapped wife and uses his storytelling abilities to outwit the perpetrator and rescue her.

Bramah published five Kai Lung books in the period from 1900 to 1940. The fourth and fifth books are 1932’s The Return of Kai Lung (also titled The Moon of Much Gladness) and 1940’s Kai Lung Beneath the Mulberry-Tree. Two more volumes of previously uncollected Kai Lung stories were also published in 1974 and 2010 as Kai Lung: Six, and Kai Lung Raises His Voice.

These are very funny, if somewhat challenging reads, due to the exaggerated writing style Bramah uses. He takes the power dynamics, the social obeisance, the respectful, self-deprecating humility found in traditional Chinese culture, and he embellishes them with clever wordplay full of ribald jokes, veiled insults, insincere flattery, and a deep sense of irony.

Bramah parodies ancient Chinese culture somewhat in the books, but he does it respectfully rather than with disdain. He clearly had a soft spot in his heart for Chinese customs and beliefs. His accurate attention to detail in describing its people, places and practices was far superior to the rude or simplistic caricatures of China found in the works of many of his contemporaries.

He’s not completely faithful to Chinese history or culture, though, as he occasionally sprinkles in references and social satire from his merry old England, but disguised as Chinese.

The protagonist, Kai Lung, is a truly memorable character. He’s a bit of a rascal himself. He doesn’t exploit others around him like a true rogue might. He’s content to be a bum, but he also takes delight in slyly tweaking the noses of the stuffy, the pompous and the powerful through the tales that he tells that display a very droll, understated sense of humor.

The verbose wordplay can be a little exhausting to read in one sitting, but the structure of the books as a series of short tales, many of them fantastical in nature and inspired by Chinese mythology, makes them easy to tackle in bite-sized chunks.

The Kai Lung stories were quite popular in the first half of the 20th century, and many common Chinese-sounding sayings and aphorisms have been attributed to Bramah over the years, perhaps apocryphally, including the well-known curse “May you live in interesting times.”

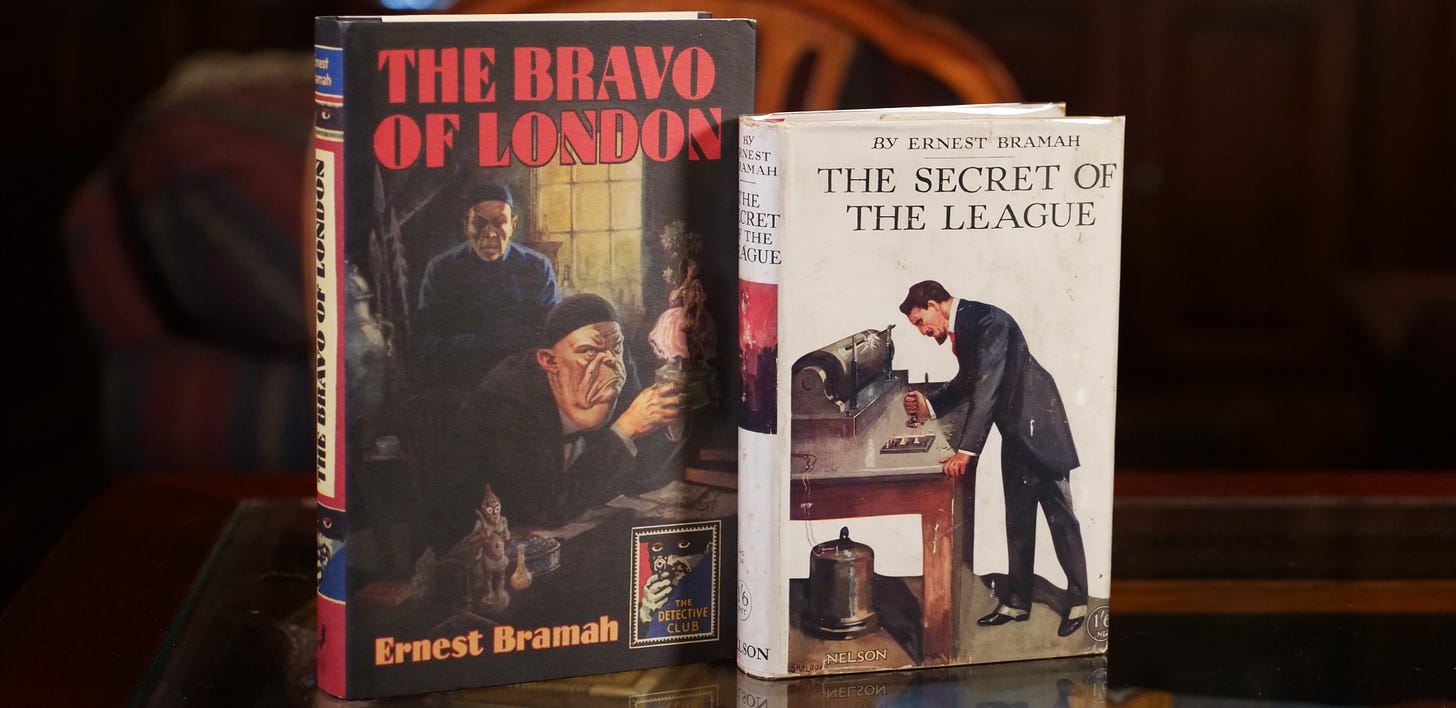

Finally, Bramah was an eclectic author. In addition to his Kai Lung books, he penned a series of popular whodunit stories, starting in 1914, featuring a blind detective named Max Carrados who compensates for his loss of vision with heightened sensitivity of his other senses that he uses to solve his cases.

He also wrote an early and influential dystopian science fiction novel, The Secret of the League, published in 1908, that George Orwell credited with inspiring his novel Nineteen-Eighty-Four.

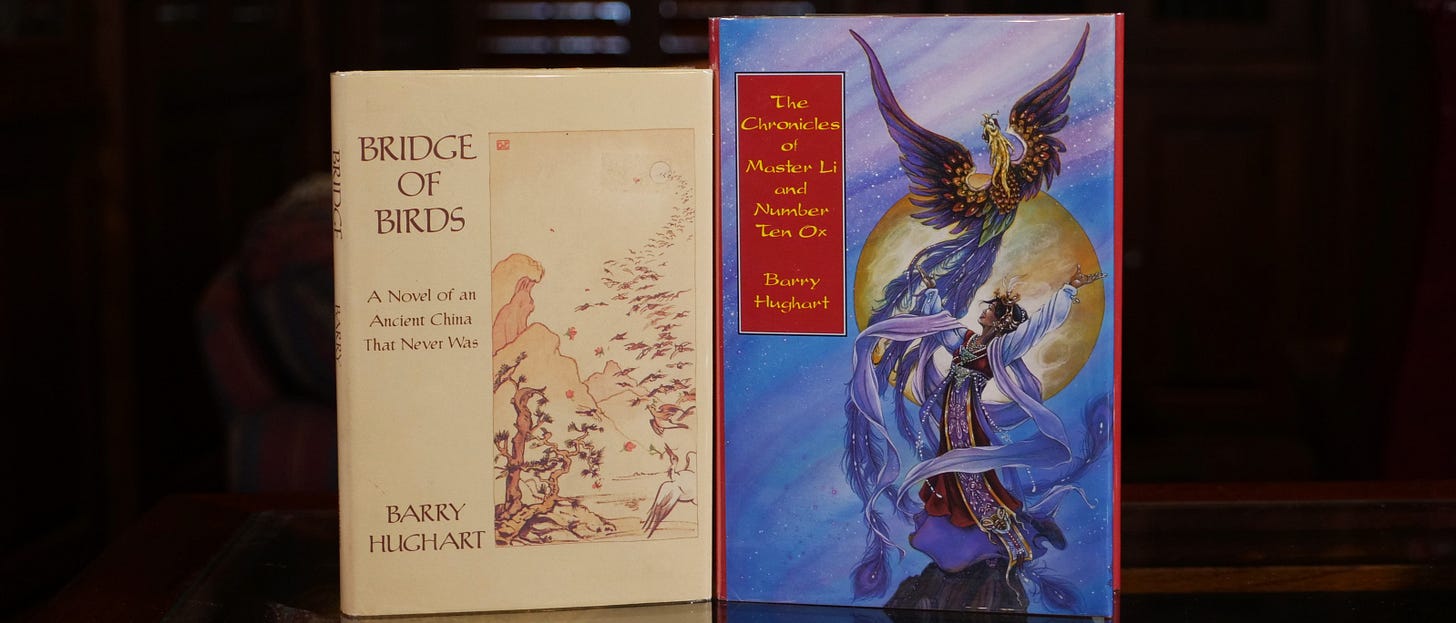

An Ancient China That Never Was

Barry Hughart published his debut novel, Bridge of Birds, to critical acclaim in 1984, as it won both the World Fantasy Award and the Mythopoeic Award for best fantasy novel. It was the first in a trilogy of novels Hughart wrote known as The Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox. The other two novels in the trilogy are 1988’s The Story of the Stone and 1990’s Eight Skilled Gentlemen.

The three novels are part of a memoir recounting the adventures of Master Li Kao, an infamous, age-wizened scholar, and his young assistant, Number Ten Ox, a brawny, well-intentioned and somewhat naive peasant.

Master Li is brilliant, crafty, and possessed of such high self-regard that he claims to have only one slight flaw in his character. In his younger days, he was an advisor to emperors, a consort to empresses, a renowned intellectual, a poet, a spy, and an assassin.

Now in his old age, he’s a washed-up drunk, a social outcast, and a clever con artist. He’s an irascible, lascivious and unethical scoundrel, but one who still has a moral compass that leads him to do what’s right when it matters most.

The first book, Bridge of Birds, tells of Number Ten Ox’s search for a cure for the children of his village who have suddenly and mysteriously fallen into comas. After his appeals for aid are refused by every reputable scholar he can find, the disreputable Master Li becomes his only hope.

Thus begins a fantastical quest to find the supremely potent ginseng Great Root of Power as well as the fabled Princess of Birds. Deities and other immortal beings make appearances, while perfidy lurks at every turn, making it hard to tell friend from foe.

At times, the novel feels like a humorous crime caper of the Donald Westlake variety, as much of the story consists of a series of increasingly high-stakes heists full of elaborate plans, unexpected mishaps, and daring escapes. At other times, it feels almost philosophical, exploring pseudo-Chinese mythology as Master Li and Number Ten Ox each search for a higher purpose in life.

The second and third books in the trilogy tell of later adventures of the duo involving murder mysteries with mythological beings as the prime suspects. Like Bridge of Birds, their plots have a complicated, nested structure, with quests within quests, and stories within stories.

But you don’t have to worry about getting lost, because all three novels are quite short. Each is only a little over 200 pages long.

I heartily recommend this trilogy. It’s absolutely delightful, combining the insouciance and storytelling charm of Ernest Bramah’s Kai Lung, the ethereal descriptiveness of Lord Dunsany, and the roguish humor and embedded mysteries of Jack Vance. There’s no doubt in my mind Hughart must have been a fan of all three of those authors.

Finally, Hughart does take some creative liberties with Chinese history and folklore, which he acknowledges up front in the first book’s subtitle—‘A Novel of an Ancient China That Never Was.’ Nevertheless, many aspects of the books are quite faithful. They’re an homage, not a parody, as the author was a longtime admirer and student of Chinese history and culture, including classic Chinese literature.

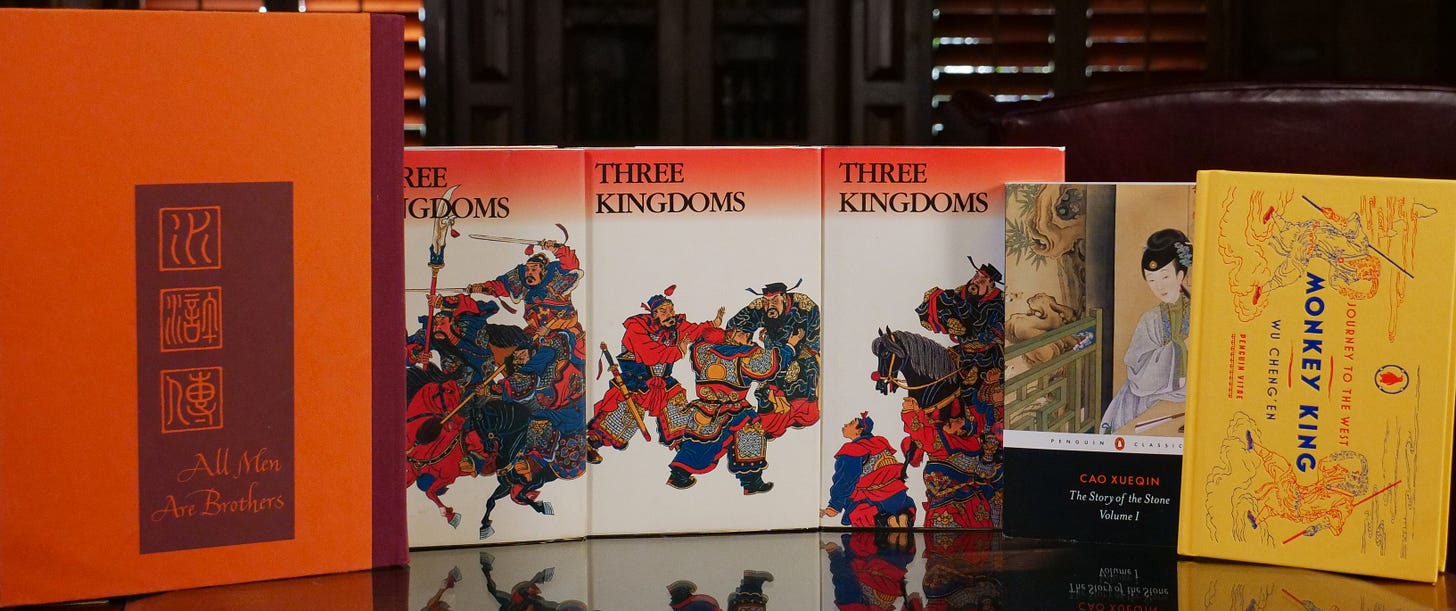

Elements of the Chinese epics The Water Margin, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Dream of the Red Chamber, and Journey to the West can be found in the adventures of Master Li and Number Ten Ox. The second book in the trilogy, The Story of the Stone, even borrows its title from an alternate title of Dream of the Red Chamber.

Read this trilogy. I’d been aware of it for decades, but had never gotten around to reading it until a few months ago. I’m kicking myself for waiting so long, because it was one of my favorite reads of last year. Unfortunately, they’re the only novels the author ever published.

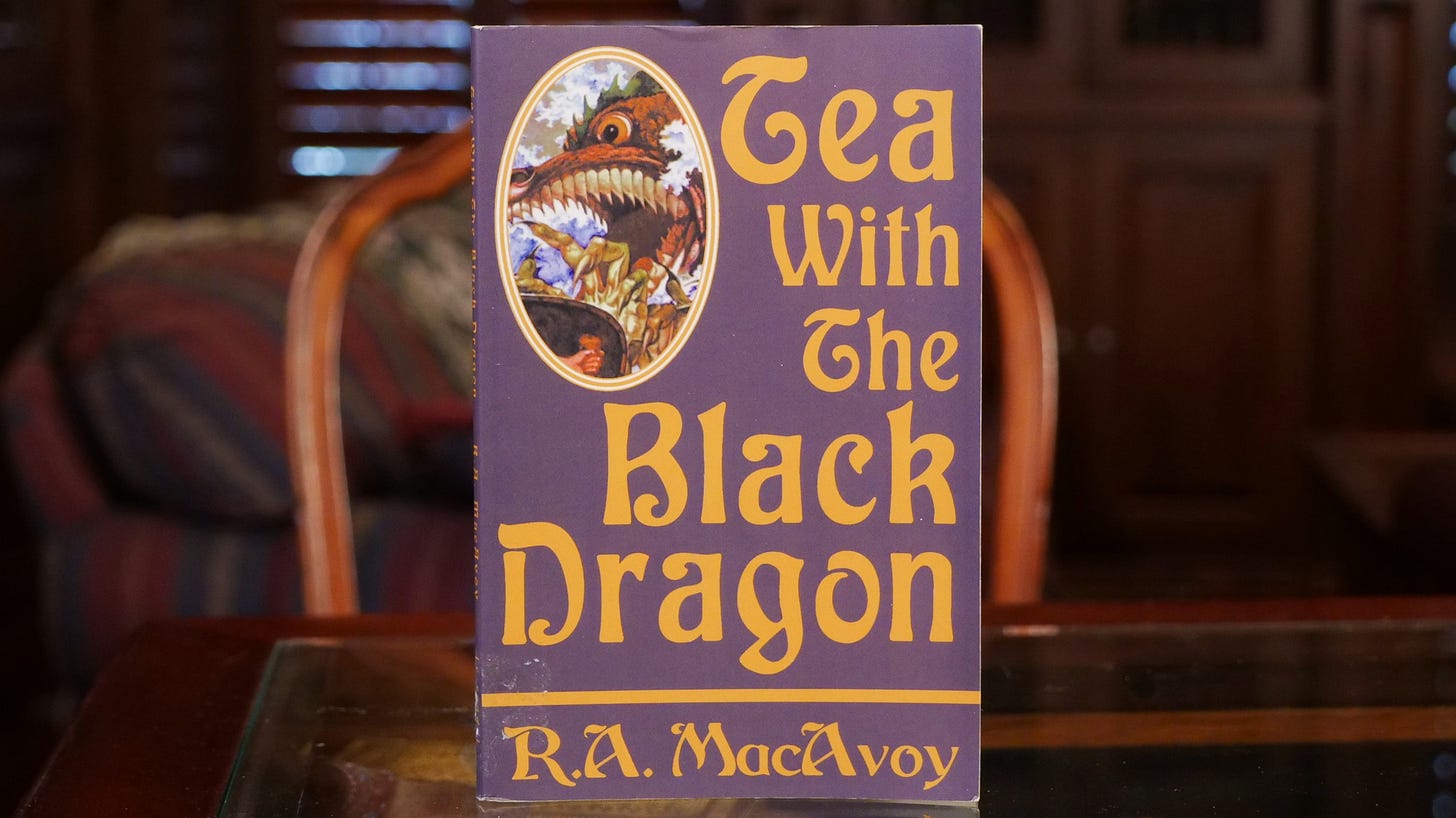

Retro-Techno-Thriller with Dragon?

The final book I want to discuss is possibly the strangest one on this list. It’s a cross-cultural May-December romance. It’s a mystery involving the search for a missing young woman. It’s a techno-crime thriller featuring obsolescent, 1970s technology. It might even be a fantasy . . . about dragons. And it accomplishes all that in a very slim, 128-page volume.

R.A. MacAvoy’s 1983 debut novel, Tea with the Black Dragon, is a charmingly odd book that captivated readers and critics alike when it was first published. Its focus on Chinese culture was uncommon at that time, as was its unusual blending of different genres.

At its center is a tentatively flirty relationship of the will-they-or-won’t-they variety between middle-aged Martha MacNamara and a much older, but seemingly ageless, Chinese gentleman named Wayland Long who she meets ‘cutely’ in a chance encounter.

Martha’s daughter, a computer programmer, has gone missing under mysterious circumstances, and Wayland offers to help Martha find her. The duo act like amateur sleuths, tracking down leads, questioning potential suspects, and working with computer technology and gadgetry that might have felt a little dated to readers at the time the novel was published.

The CP/M operating system and high-speed cassette tape decks featured in the story were cutting edge in 1975, but by 1983 were rapidly becoming obsolete with the introduction of Microsoft DOS and floppy disk drives.

As an aside, my very first computer was one my dad built from scratch in 1978. It had a Z80 processor, 32K of RAM, the CP/M operating system, and a high-speed cassette drive with four tape decks—basically, the same rig Martha and Wayland are eager to get their hands on in this novel five years later.

Tea with the Black Dragon was originally marketed as a fantasy novel, and is still frequently described as such, but the fantasy aspects of the story are tenuous and mostly limited to ambiguous hints Wayland drops that he might be a 2,000-year-old dragon in disguise.

It was a finalist for the 1984 Hugo and Nebula awards, and it won MacAvoy the Locus and John W. Campbell awards that year for best new writer.

I don’t think reading it today has quite the same impact it did 40 years ago. Some aspects might feel a little too familiar now, while others might feel a bit dated. Still, it’s a pleasant little romance with bits of computer code, gunfights, chase scenes and the possibility of dragon fire mixed in.

It deserves not to be forgotten.

I hope some of the Chinese-inspired works I discussed in this post have piqued your curiosity enough to give them a try. I think they’re all rewarding reads.